Remember, remember, the 5th of November,

Gunpowder, treason and plot.

I see no reason

Why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot.

Guy Fawkes, Guy Fawkes, 'twas his intent

To blow up the King and the Parliament

Three score barrels of powder below

Poor old England to overthrow

By God's providence he was catch'd

With a dark lantern and burning match

Holler boys, holler boys, let the bells ring

Holler boys, holler boys

God save the King!

The Gunpowder plot is one of the few really well-known political events of the early modern period in England and Britain – up there along with, say, the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588), and the battles of the English Civil War (1642–46, 1648).

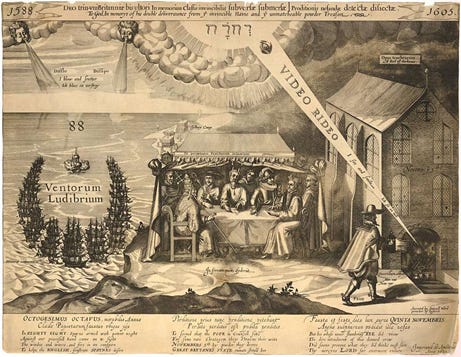

But what does Gunpowder Plot signify even to those who ‘know’ about it? For many, it is merely associated with the annual 5 November jamboree – bonfires, and exorbitant profits for merchandising and fireworks companies. Perhaps a few more people might make the connection with the mask of the resister of tyranny in V for Vendetta? A few more will remember those contemporary drawings of the plotters, gathered together in some sort of seditious huddle, wearing impossibly large hats.

A contemporary engraving of eight of the thirteen conspirators

An obvious default position is one of satire – the famous date itself (5th November) has been an object for humour – witness the talented and cerebral John Finnemore’s sketch in which the millennial-sounding plotters consult their diaries to see which would be the most convenient day for blowing up Parliament.[1]

Even for those who have a mind map of the outline of early modern political events, the topic remains fairly opaque. What are we supposed to make of it now? Was it simply an isolated ‘terrorist’ incident – a catastrophic disaster narrowly averted? Was it evidence that Catholics (whoever the ‘Catholics’ actually were) were all seditious radicals? What about all those stubbornly persistent stories that it was a black-ops manoeuvre by the new regime? The letter which alerted the regime to the imminent catastrophe has, for some commentators, seemed just a bit too convenient.

The anonymous letter sent to William Parker, Lord Monteagle, 26 October 1605

The problem with virtually every modern account of the plot is that they find it difficult to come to any coherent conclusion. By far the best popular narrative of it, written over quarter of a century ago by Lady Antonia Fraser, summed it up by saying that the plotters were terrorists who failed, and that they were ‘brave, bad men’.[2]

Bravery and badness are, however, not really, of themselves, properly historical categories. Yes, the ‘extraordinarily dramatic story’, as Lady Fraser calls it, was marked by ‘tragedy, brutality [and] heroism’, but, if the plotters were really planning to do what they were alleged to have attempted, there might be more to say about it than that.

We do not, of course, have a first-hand manifesto from the conspirators’ leader, Robert Catesby (c.1572–1605), as to what he actually wanted – other than, presumably, in the first instance to see dismembered bodies strewn all over the ruins of the Parliament building at Westminster – a kind of early seventeenth-century equivalent of 9/11.

My impression is that the whole literature around the plot is still framed by the existing but often outdated accounts of the Stuart court in England. That literature is heavily influenced by an older style of narrative history. This described the new Scottish king, James I of England (reigned from March 1603 – March 1625), as a buffoon. In other words, as a clumsy oafish foreigner who was out of his depth in a sophisticated monarchical state such as England – Inspector Clouseau-like in what he took to be his own cleverness, but quite unable to understand his new subjects. On this telling King James was either too busy eyeing up the more attractive young men around court to pay attention to public business, or else was out on the hunt, trying to slaughter defenceless animals in the countryside. Where, briefly, he did turn to politics, his ludicrous interludes and interventions inevitably had to be deflected and contained by his conscientious English counsellors.

Some of these narratives are reminiscent of Yes Minister – Robert Cecil, earl of Salisbury’s Sir-Humphrey-ish ingenuity was necessary in order to deal with his master’s stupidity. Even the discovery of the Gunpowder plot was Cecil’s achievement.

Portrait of James I of England (c.1605)

On the surface, the narratives of the conspiracy itself seem, frankly, strange. Are we genuinely supposed to believe that the plotters, contemplating mass murder, waited for months and months before attempting it? The project was fraught with risk, and yet they apparently informed more and more people, with the likelihood that their ‘secret’ would not remain secret for very long. To cap it all, we are told that they were ‘men of faith’ who had embraced true religion. And yet they wanted to massacre not just the king and his family but also the State legislature – including a fair few of their own relatives.

Not only this, but the plotters allegedly consulted high-profile spiritual advisers – Catholic clergy, Jesuits in fact – as to whether it might be allowable for a good Christian to blast parliament and its members to smithereens. How could it possibly be that in the same family some people, especially women, could lead lives of demonstrable piety, and even take themselves off to become nuns in foreign convents, leading lives of austere claustral piety, but some of their menfolk plotted arguably the worst crime of the period – allegedly all in the same cause?

Moreover, the principals in this alleged conspiracy were of the highest social rank – in an era when birth, breeding and lineage were of paramount importance. We can still see some of their ancestral homes in the modern-day English countryside – striking physical architectural statements about wealth and power. For these families, what mattered was heredity, marriage and descent. The way to secure these things was through interaction with the county community – again, through affinity with other wealthy families. Why would such people forget all these things and enter into a futile treason when it was so contrary to their families’ material interests?

It is not often remarked upon, but there is, in reality, apart from, for example, the transcripts of the trials of the surviving conspirators, only one really major ‘insider’ source for the Gunpowder plot, that is to say, the narrative in English by the Jesuit John Gerard (1564–1637), written in 1606.[3] It works in several different genres – political narrative, godly-life-writing and martyrology but also, as scholars use the term nowadays, ‘secret history’. And it uses these to weave together a set of arguments about the relationship between political authority and freedom of conscience.

In the language of contemporary politics, ‘secret history’ had a precise meaning. It was a genre in which political activists used the printing press (as well as the circulation of manuscripts) to set before the public the ‘truth’ of events at court, and in other locales where power was exercised, to allow them to see ‘what was really happening’, and to make up their minds about it, and in particular to alert them to the wrong-doing of those in authority.

In recent times, there had been a number of such pieces from the pens of Catholic exiles. Some contemporaries would remember the headline-grabbing scandalous secret histories published in the 1580s, for example ‘Leicester’s Commonwealth’ with its stories about Robert Dudley (1532–1588), 1st earl of Leicester and his evil doings. Then there was the work of Nicholas Sanders (c.1530–1581), an English Catholic priest who had narrated the course of the English Reformation. In doing so, Sanders notoriously pointed to the shocking corruption of Henry VIII’s court.

Just before King James took the English crown in March 1603, the English public had been able to access a spate of vicious tit-for-tat pamphlet-based conflict put out by opposing groups of Catholic clergymen. Some of these pamphlets included secret histories of the recent past. Self-styled loyalist Catholic clerics said that the Jesuit clergy and their patrons were seditious men who engaged in treason. To this end, they printed various documents and even private correspondence to prove to the public that they were telling the truth. Jesuit clergy retaliated by saying that these so-called loyalists had sold out to a heretical regime. Each side accused the other of being involved in, in effect, conspiracies against true religion.[4]

This was one significant context for the Gunpowder Plot – in which the public could view competing, equal-and-opposite, conspiracy theories – canvassed to the public through a series of claims and counter-claims about treason and loyalty.

The fact is that many politically controversial events and issues tend, in the public domain, to resolve themselves into competing conspiracy theories. Take, for instance, any recent highly publicized controversy that might come to mind that has been played out on a local, national or global scale. Then think about how many conflicting, indeed polarizing narratives there have been about it. No doubt your example might include an origin story and the vested interests of the various players (most likely governmental figures or at least those holding positions in authority, wherever that might be located). Your example may even include an ‘official’ cover-up – regardless of whether or not you regard this account as ‘true’.

What I would like to suggest here is that the vast majority of people (but not all, of course) have no empirical way of resolving a whole range of hot-button controversial issues. In the case of most of them, the general public’s views – shaped as they are by their consumption of mainstream and / or alternative media – will be largely conditioned by other political issues which have little or nothing to do with the technical issues involved in the recent highly publicized controversy that might have come to mind. In short, most people lack the technical expertise in the given subject under discussion. Consequently they are susceptible, dare it be said, to competing forms of propaganda designed to shape or perhaps reinforce their thinking about an issue in which they lack sufficient in-depth understanding. Throw in more difficult to discern forms of propaganda, for instance so-called government sponsored behavioral insights teams, i.e. ‘nudge units’, and one can often guess which way, at least under certain circumstances, the majority of people might react to the said controversial issue.

Perceptions of what is ‘good’ and ‘bad’ here raise questions about not only the motivation but perhaps also the lack of perceived knowledge about the subject among those who disagree with the prevailing narrative. This leads to the rise of conspiracy and counter-conspiracies in order to explain why the ‘other’ (whoever the ‘other’ is) chooses to pursue a self-evidently wrong course. And so, I contend, it was with the Gunpowder conspiracy.

There had already been public arguments. For example, even before the accession of James VI of Scotland as James I of England and Great Britain in March 1603, there had been a dispute about whether, when he took the crown, there would be too much Scottish influence in the English State and the English Church. The Scottish Kirk, after all, had characteristics which, at least to some, looked all too like English puritanism – particularly that irritating tendency to speak truth to power. It was something that Queen Elizabeth herself had found intensely annoying.

Elizabeth’s later years had seen churchmen such as Richard Bancroft (1544–1610) afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury, attacking puritans. James himself had faced down his more vocal critics in the Kirk – would he ally himself with the enemies of puritanism in England? Or would he import aspects of Scottish presbyterianism into the English Church? Some English puritans undoubtedly hoped that this was what he would do. But in Scotland he had seemed to be all too friendly to leading Catholic peers – would he behave in the same way in England?

It rapidly became clear, after March 1603, that the Scottish king had made too many potentially incompatible promises to too many people (though he would hardly have been the first, or last, political figure to do that). It was impossible, as he undoubtedly knew, to resolve all the issues that his public declarations and private assurances, before he took Elizabeth’s crown, had raised. He had lit the touch paper, as it were, for a train of events that, in some ways, led directly to the cellar under the houses of parliament in November 1605. Perhaps, for that reason alone, it is worth looking back to the episode that we call the Gunpowder Plot but which is about much more than merely the existence of the bomb – which undoubtedly did exist and would, in all likelihood, have worked, had it gone off at the right time.

That was, in fact, not John Gerard’s principal concern, although he provided a detailed narrative of what the conspirators had done. In a classic piece of apologetic writing, he not only refuted the accusations that the English Jesuit priest Henry Garnet (1555–1606) and several other clergymen had known, at least in detail, about what was being planned. He also presented a view of the post-accession political scene – one in which the court was being corrupted by people on the make, as a result of which others were provoked beyond measure, and catastrophically by the new laws passed in the 1604 Parliament against Catholics.

In so doing, Gerard provided sketches of the plotters and their actions which have been used, ever since, by historians and television programme makers. He described them as dashing and courageous – their real crime was not to open up to their confessor-chaplains about what they had decided to do. The implication here was that if senior Jesuit clergy had known what was being planned they would have properly intervened to prevent it.

Execution of Gunpowder plotters, 1606

Still, the fact was that the enforcement of the iniquitous legal penalties against good Catholic Christians had driven conscientious individuals to despair. Gerard’s text made the case for religious toleration in the future, in which the people whom he represented were restored to the regime’s good graces. Gerard argued that, whatever Robert Catesby and his companions had done, it was as nothing compared to the general threat from the truly malign puritans who were inimical to the King’s and the Commonwealth’s real interests.

This might seem like the most specious sort of special pleading – it was in part, of course, also meant to stave off the inevitable assault from the Jesuit clergy’s Catholic critics who indeed, early in 1606 dispatched agents to Rome to demand that something should be done about the recent sedition, and which they were happy to attribute, as the Jacobean regime did, to the Society of Jesus.

But Gerard was not simply whistling in the wind. By 1609, Bishop Lancelot Andrewes (1555–1626) could, in preaching on the Gunpowder Plot, concentrate on puritans as the vectors of sedition. In these circumstances it was not surprising that other highly placed people inside the regime (the ones whom Gerard and other Catholics tended to associate with puritanism) claimed that the hunt for the plotters had not gone far enough – indeed, that there had been many more implicated, around the fringes, and that it was the regime’s duty to hunt these people down.

But significantly, towards the end of the 1610s, some Protestants started to worry that the king and his closest advisers no longer seemed to be as exercised by the threat of popish sedition as they had once been. Controversially, in 1618, not long after the Elizabethan courtier Sir Walter Raleigh had had his head hacked off, the king decided to release William Baldwin (1563–1632), the imprisoned Jesuit who, it had been claimed, had known about the plot.[5]

This was one of the contexts for the new directions taken by King James towards the end of his reign, and for the conflict between the crown and its critics, particularly in the Parliaments of the 1620s. The memory of the plot, which had once been a vehicle for expressions of loyalty, became a potentially hostile critique of the alleged failings of Stuart monarchy.

[1] John Finnemore’s Souvenir Programme, BBC Radio 4, November 2014.

[2] Antonia Fraser, The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and Faith in 1605 (1996), pp. 285–86.

[3] J. Morris (ed.) The Condition of Catholics under James I: Father Gerard’s Narrative of the Gunpowder Plot … (1871). For the narrative (in Italian) by Oswald Tesimond SJ: F. Edwards (ed.), The Gunpowder Plot: The Narrative of Oswald Tesimond alias Greenway (1973).

[4] Peter Lake and Michael Questier, All Hail to the Archpriest (Oxford, 2019).

[5] Fraser, The Gunpowder Plot, p. 277.

That's very kind of you - I much appreciate it!!

Many thanks, I'm glad you liked it!