'Beastly fury and extreme violence' - part three

III. FOOTBALL AND CAMPYNG

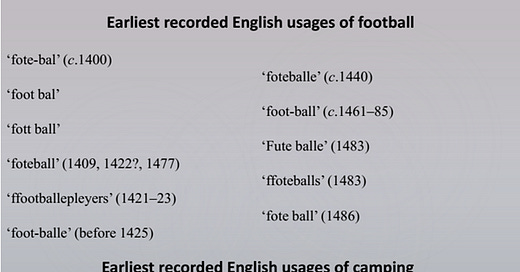

Since the first British references to football are in French and Latin, it is not until the early fifteenth century that we have the earliest recorded English usages: ‘fote-bal’ (c.1400), ‘foot bal’, ‘fott ball’, ‘foteball’ (1409, 1422?, 1477), ‘ffootballepleyers’ (1421–23), ‘foot-balle’ (before 1425), ‘foteballe’ (c.1440), ‘foot-ball’ (c.1461–85), ‘Fute balle’ (1483), ‘ffoteballs’ (1483), and ‘fote ball’ (1486). Interestingly, a variant played in Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk was known as ‘campyng’ (c.1320, 1421, c.1460), ‘Kampyn’ or ‘campar’ (c.1440). This is significant because since the seventeenth century philologists have derived its meaning from the Anglo-Saxon for ‘striving’ or ‘contending’, or the Old English ‘campian’ meaning ‘fight’. So it is against this backdrop that we should situate our next pre-Reformation examples.

At a court leet held on 14 June 1320 in the coastal village of Hollesley, Suffolk four pairs of men were charged with ‘bloody assaults’ during what a later hand clarified as ‘campyng’. John Ridgard, who discovered the entry in the court rolls, has suggested that the men had been involved in one or more camping matches that may have been played during Whitsuntide. Furthermore, two of the players were brothers, members of an influential villein family. Yet apparently they represented opposing sides. Further north outside the town of [King’s] Lynn, Norfolk a boy accidently died in the mid-fourteenth century as a result of playing a ball game, while a man was murdered following a quarrel arising from football. Sometime later in 1421 one Thomas Stowne of Copford, Essex was tried for assaulting Richard Stogg with ‘quodam campyngrock’. Moving from East Anglia to London, a coroner’s inquest in June 1337 heard how on Tuesday in Pentecost week the son of a chandler ‘got out of a window … to recover a ball lost in a gutter at play’. But the boy slipped and fell, injuring himself so badly that he died the next Saturday. Again in London, in 1373 eight men were brought to the Mayor’s court to answer a charge that they, together with others:

with force and arms, to wit, swords and knives, made an assembly, under colour of playing with a football, in order to assault others, occasion disputes, and perpetuate other evil deeds against the peace in Sopers Lane, Cheap and Cordwainer Street.

Two of the men were pelters and six were tailors, so they may have had common commercial interests dealing or working with animal skins. While one pelter and one tailor pleaded not guilty, the remainder claimed that although they had played football they had ‘done no harm’. Nonetheless, one was mainprized and the rest committed to prison. Whether these men were guilty of using a football match as cover for instigating a riot in the streets of London or whether this contest got out of hand resulting in the assault of non-participants is difficult to establish. But the charge clearly links football with violence. Moreover, Taylor Aucoin has shown that the match took place on Shrove Tuesday. This is important because it is the earliest known example of football played on that day, and one of only a handful before the Reformation.

London Metropolitan Archives, CLA/024/01/02/19, mem.3r; alleged riot while playing at football on Shrove Tuesday, 1373

Heading north, between 1377 and 1383 a number of villagers who were tenants of the prior and convent of Durham were warned against playing a ball game under penalty of a fine. Thus the constables of Aycliffe, Ferryhill, Heworth and East Merrington were threatened with a 20s. or 40s. fine if they permitted any ball play. Even so, at Southwick in 1381 there was an affray when the prior’s tenants were menaced by those of a local lord so that they were ‘in grievous peril of their bodies’. The cause was a ball game which precipitated ‘grievous contention and contumely’. Again, at Aycliffe in 1383 seven men including William Colson and John de Redworth – presumably constables – were presented and threatened with a 20s. fine for failing to report ball playing in their village. Under pressure from Redworth’s wife Alicia, who would not keep quiet, they in turn presented eighteen men for ball playing (including a member of Colson’s family). It has been suggested that these Durham villagers had been playing football. This is very likely, because in 1446 an elderly villager originating from the barony of Brancepeth in Durham recalled that one day he saw around sixty people ‘playing football at Helmington Row in the barony’. They all shared the same surname (Oll) and were accounted ‘among the best’ valets [attendants] and freemen of the barony; certainly not of servile status. Furthermore, in spring 1386 some villagers of Billingham were amerced for playing football, while in spring 1467 sixty-two tenants of Billingham, Wolviston and Aycliffe were amerced for the same offence. Again in spring 1478, in accordance with legislation enacted earlier that year, all Aycliffe tenants, of which eight were named (doubtless constables), were warned against playing prohibited games – notably dice, cards and football – under penalty of a 20s. fine. Later still, in spring 1492 an injunction permitted football to be played at Billingham twice a year while stipulating that ‘he who makes an affray on those days forfeits to the lord forty shillings’. According to Peter Larson, for its part Durham Priory ‘cracked down on the game only sporadically’. This indicates that ‘the bursars usually tolerated football despite its illegal status’. Even so, the Priory issued an injunction against football in spring 1506 suggesting that this had been prompted by increased violence.

Moving from Durham to Yorkshire, in 1409 members of the lower clerical orders and others were reproved for playing ball games within the close of York Minster. In 1422 a woman from Wistow deposed that a couple had contracted their marriage, in the words of Jeremy Goldberg, ‘on Ash Wednesday at the time when the men of Wistow play football’. Such testimony, however, is problematic and should not be taken at face value. This can be seen from a similar case the next year at Church Fenton when one Thomas Newby claimed that he could not have married Beatrice Pulayn on Sunday, 4 July 1423 because that particular afternoon he was playing football in nearby Barkston until sunset and then went drinking. Yet the likelihood of mendacious witness testimony and Newby’s own evasions suggest that his alibi may not have been watertight. Seemingly more straightforward is an inquest into a murder committed some forty or so years later. During a football match at Pontefract on Shrove Tuesday 1477 one Leonard Metcalf accidently hit Robert Pilkington with his ball. Pilkington drew his dagger worth 20d., prompting Metcalf to apologise. Metcalf then attempted to resume his game, at which point Pilkington knifed him in the heart. Pilkington had also set fire to a chapel and stolen cattle, for all which crimes he was sentenced to hang. Nonetheless, he was reprieved after claiming benefit of clergy. Less violent were several incidents connected to a dispute about access to land in the vicinity of Shap, Cumberland. A tenant of Sir Thomas Curwen, one of the contending parties, had been ‘sore hurt att ye foteball’ by a servant of Thomas Salkeld, the opposing party. Consequently Curwen was awarded 2s. compensation in a judgment of February 1474 which noted that another tenant had likewise been beaten and ‘sore hurte’. There is also the presentment of two Northallerton men, one of whom afterwards became a borough court juror, who in 1495 were fined 3s. 4d. for causing an affray during a football game played on the Applegarth just outside the town. At the same time the steward imposed an ordinance, mandated by the bishop, forbidding the playing of football on penalty of a 6s. 8d. fine. Similarly, in 1500 football was prohibited at Hartley, Northumberland under penalty of a 6s. 8d. fine. Several years later in 1519 parishioners at Salton, Yorkshire were threatened with excommunication for playing various ball games with their feet and hands in the churchyard – namely tutts, handball and penny-stone.

Down south, between 1422 and 1423 the Brewers’ Company in London let their hall to seventeen different fraternities including on three occasions to a group of football players for 1s. 4d. This contrasts with the censorious attitude of certain London citizens who in July 1446 complained about the erection of several places where people played at ball [tennis?], ‘cleche’ [closh?] and dice, adding for good measure that these structures served as brothels. Even so, tennis continued to be played in London as attested by the fame of a skinner named Richard Steris, accounted one of the ‘cunnyngest players’ in England, but whose remarkable agility did not save him from being beheaded for treason at Tower Hill in 1468. Over in Suffolk, Robert Cook, rector of Martlesham was the subject of several complaints: gambling, assaulting a woman and playing tennis in his shirt and breeches in the market square at Woodbridge on the Sunday after Midsummer Day, 1431. To the north in the same county, John Hardgrave of Beccles recorded in the early 1430s that:

The men who played at football on the ice and sank through have caused great misery by their deaths to their friends, who propose to hold their funeral rites next week.

However, since Hardgrave was then likely a teenage student of Latin grammar it is unclear whether this referred to an actual event or was merely a school exercise.

Elsewhere, there were prohibitions against playing handball or quoits and then ball games generally at Tamworth, Staffordshire (1424, 1436, 1446); against club ball, football and handball at Castle Combe, Wiltshire (1447, 1452); against handball and dice at Wimbledon (1464); and against tennis, quoits and dice at Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire (1469). Moreover, there were fines issued at Carshalton, Surrey for playing at handball (1446, 1447), and likewise at Pagham, Sussex (1482), while in August 1450 a currier, barber and glover swore on the Gospels to abjure the game of tennis within Oxford and its precincts. Furthermore, four parishioners of Tillingham, Essex were presented for playing dice and a ball game during divine service (1458). Moving forwards, tennis, bowls, closh, dice and cards were prohibited at Worcester under penalty of imprisonment (1496); a dozen men were fined for playing tennis at Ampthill, Bedfordshire (1502); and servants were banned from playing tennis or unlawful games on work days at Rye, Sussex (1504). At Wells Cathedral two perpetual vicars were admonished in July 1507 for playing handball instead of coming to matins on the vigil of the translation of St Thomas the Martyr. At the manor of Kirton in Lindsey, Lincolnshire a jury presented one William de Welton in April 1510 for misbehaving himself in playing football and other unlawful games. Master Richard, the curate of St Mary’s in Hawridge, Buckinghamshire was suspended in 1519 for, among other things, playing dice and being a ‘common player at football in his alb’ [an alb was a white vestment worn by clergymen which reached their feet]. And the inhabitants of Hayes, Middlesex were charged by their parson in 1534 with playing unlawful games: bowls, football, dice and cards as well as with committing riots – though no blows were given or weapons drawn. By contrast, the churchwardens of Heybridge, Essex received 18s. 3d. for the ‘campyng sporte’ in 1518–19, while their counterparts at Cratfield, Suffolk spent 4d. ‘for a ball to camp wyth’ in 1534.

IV. TESTIMONIES

Thus far questions as to the extent to which we can rely upon witness testimony, not just recollections of sporting injuries and fatalities but even memories of when and where games were played, has largely been avoided. With the deceased unable to have their say in court, defendants who appeared personally would have had to contend with versions of what happened presented by other eyewitnesses (some of whom may have been the deceased’s friends and family) when framing what would doubtless have been self-serving narratives. Yet despite this caveat too many scholars appear to have readily accepted as genuine all or most aspects of events recounted at coroners’ inquests and the like. The same can be said of equally – if not more – problematic evidence: proofs of age. Essentially for our purposes they were legal proceedings to determine someone’s age and hence their inheritance rights. This is particularly important with regard to football since on the face of it there are a dozen known cases involving witnesses claiming to remember a game played several years previously on the day of the prospective heir’s birth or baptism. Two such proofs of age from Sussex early in the reign of Henry VI are well known, having been published in the 1860s. Indeed, their similarity has been noted though their content was assumed to be true. Since then many more examples have come to light, all but one helpfully collected and made accessible through the Mapping the Medieval Countryside project.

Taken together, proofs of age seemingly provide evidence for football being played at Wolviston, Durham (Shrove Tuesday, 1380); Stamford, Lincolnshire (feast of the Annunciation, 25 March 1397); Chelmsford, Essex (Tuesday, 22 June 1400); Little Laver, Essex (Tuesday, 18 October 1401); Thorpe-le-Soken, Essex (Tuesday in Pentecost week, 16 May 1402); Layer Marney, Essex (Monday, 14 August 1402); Wilcote, Oxfordshire (Wednesday, 1 August 1403); Selmeston, Sussex (Friday, 24 August 1403); Chidham, Sussex (Tuesday, 23 September 1404); Odell, Bedfordshire (Sunday, 28 September 1410); Dry Drayton, Cambridgeshire (Sunday, 21 February 1417); and Sproughton, Suffolk (feast of St Nicholas, 6 December 1421). Moreover, in seven instances – at Chelmsford, Little Laver, Thorpe-le-Soken, Layer Marney, Selmeston, Wilcote and Chidham – a man supposedly broke his left shin; at Sproughton his right shin; at Wolviston and Odell an unspecified shin; and at Dry Drayton his left arm.

Even so, research by Matthew Holford has shown how during the first half of the fifteenth century ‘fictional testimonies became ever more common’ and that from 1418 to 1447 an increasing number of proofs of age were copied or adapted from earlier proofs (ranging from 20% to 46%). In this light, the four Essex cases can immediately be identified as fictitious since they share too many similarities. This was recognised more than a century ago by R.C. Fowler who observed that recollections of supposed events at Chelmsford, Little Laver, Thorpe-le-Soken and Layer Marney contained twelve common elements. Among them were apparent memories of someone dying and being buried; being injured at football; holding a burning torch at a baptism; falling off a cart laden with hay and breaking their left arm; seeing their house burnt; and someone else hanging themselves. The Oxfordshire and Sussex cases are likewise fictitious since these witness testimonies very closely resemble those from Essex, although the two Sussex proofs of age supply an interesting variant: a man’s servant captured by the French and carried away to Harfleur. At the same time, these cases should not be collectively discarded since their evident plausibility is also revealing: it must have been considered unremarkable to pretend in court that football was played in these regions of England at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Moreover, it must have seemed credible that an adult male could have had their shin broken in a game played after the baptism of an infant.

The remaining five cases differ from the Essex, Sussex and Oxfordshire examples, as well as from each other. Comparing them with proofs of age that do not refer to football, they contain varying degrees of non-replicated testimony. Of these, the recollected events at Dry Drayton and to a lesser extent at Sproughton are the most dubious since they include common motifs: celebration of first mass; strong wind damaging the church belfry or someone’s house; fatalities; and suicide. Nevertheless, each incorporates sufficiently original testimony for it to remain plausible that at Dry Drayton William Burbage, then aged 25, broke his left arm while playing football with his associates on the Sunday following the feast of St Valentine 1417; and that at Sproughton John Halle, aged 26, was playing football and broke his right shin on Saturday, 6 December 1421. At Odell it is quite possible that on Sunday, 28 September 1410 there was a lot of football played and that William Ballard broke John Cook’s shin. At Stamford there seems little reason to doubt that on Sunday, 25 March 1397 John Upton was playing football at the ‘Old Bull Pyt’. And at Wolviston it seems likely that Thomas Marshall was hit on the shin and gravely injured while playing football with others on Shrove Tuesday 1380.

While proofs of age provide us with one type of testimony that must be used cautiously in our chronological and geographical mapping of sporting injuries, recollections of miraculous healing gives us another. There are two examples. The first was presented as part of the evidence to support the canonisation of Osmund (d.1099), a former bishop of Salisbury. This was formally examined by three Cardinals in 1424. It concerns the testimony of John Combe aged 50 of Quidhampton, Wiltshire who remembered ‘playing at ball with great clubs’ ten years before in the nearby village of Bemerton. A quarrel ensued during which Combe was struck on the head and right shoulder with a club. So violent was the blow that he was apparently unable to hear or see nor move his head or arm for more than three months. Then Combe beheld a vision of a man clothed in white, shining brightly, who instructed him to make a wax model of Combe’s head and shoulder indicating on it where his wounds were. Combe was to make an offering to Bishop Osmund of this crude replica (an ex-voto). On awaking Combe swiftly recovered and thereafter offered his prayer and thanks at Osmund’s tomb in Salisbury Cathedral. This supposed miracle was corroborated by a witness.

The second example derives from an attempt by Henry VII to legitimate his rule by having his murdered half-uncle Henry VI canonized. Vernacular accounts of purported miracles attributed to the dead Lancastrian king seem to have been collected at Windsor Castle, the site of Henry’s reinterred remains, between 1484 and 1500. Amounting to at least 445 cases, 172 of these were translated into Latin by a monk, likely based at Canterbury, who added his own touches. Completed in 1500, this compilation was intended for papal commissioners. Among the extant alleged miracles was an uninvestigated and undated case concerning William Bartram. He had been playing football with an unruly crowd of people on a field in the vicinity of Caunton, Nottinghamshire. During this game Bartram was kicked in his ‘intimate parts’. As a result he ‘suffered long and unbearable pain’ until he saw ‘the glorious King Henry in a dream’, at which point the devout Bartram ‘immediately recovered the benefit of health’. The anonymous monk’s disapproving comments about ‘the game at which they had met for common recreation’, ‘called by some the foot-ball game’, remains our fullest pre-Reformation description:

It is one in which young men, rural and unrestrained, habitually propel a huge ball not by throwing it into the air but by striking and rolling it along the ground, and that not with their hands but with their feet. A game, I say, abominable enough, and (in my sound judgment), more common undignified, and worthless than any kind of game, rarely ending but with some loss, accident, or disadvantage to the players themselves. But what? The boundaries had been marked and the game had started; and, when they were striving manfully kicking in opposite directions, and [our subject] had thrown himself into the midst of the fray, one of his fellows, I do not know which one, came up against him from in front and kicked him by misadventure, missing his aim at the ball.

British Library, MS Royal 13 C VIII, fols. 62v-63r, uninvestigated and undated case concerning William Bartram, injured while playing football – kicked in his ‘intimate parts’ – on a field in the vicinity of Caunton, Nottinghamshire (before 1500)

V. ELITES AND COMMONERS

One noteworthy aspect of these sources is the absence among the laity of any adult males of elite social status. This is because they were exempt from the legislation regulating various games discussed earlier. Yet there is evidence that besides tournaments and hunting with hounds and hawks, some aristocrats and members of the royal family also played ball games. This can mainly be found in their household accounts, which tend to link these diversions with gambling. Thus in 1300 Edward I’s chaplain was provided with 100s. for the use of a teenage Prince Edward to facilitate his ludic pursuits, including what may have been a bat and ball game. Again, in 1387 Henry Bolingbroke, afterwards Henry IV, lost 26s. 8d. playing handball with two of the Duke of York’s men. In 1414 Bolingbroke’s youthful son was the recipient of a gift of tennis balls from the Dauphin of France, an insult calculated to impugn the young king’s martial ambition. This incident was recorded in several chronicles and subsequently popularised in Shakespeare’s Henry V, where it served as part of an opening scene before the Battle of Agincourt. Twenty-five years later in mid-July 1439, during an interlude in peace negotiations between England and France, Renaud de Chartres, Archbishop of Rheims, hurt his foot playing at ball near Calais. It is unclear whether this happened in a game with fellow ambassadors, but if so then this could be the earliest recorded instance of a match played between people of different nationalities. Moving forward to Tudor monarchs, Henry VII lost money at tennis between 1494 and 1499, while his son Henry VIII was a passionate player who built the Chief Close Tennis Court at Whitehall. Indeed, the king played tennis well into middle age, losing a staggering £46-13s.-4d. in October 1532 to two French dignitaries. Interestingly in 1525 Henry also had a pair of shoes made for playing football costing 4s. Over in Scotland, James I played tennis. James IV played caich (at which he staked large sums), golf and football, as shown in the expenditure of 2s. on 22 April 1497 to purchase ‘fut ballis’ for the King.

Although the football played by James IV and Henry VIII may have differed considerably from the variants of the game played outside their courtly circles, the almost complete absence of royal and aristocratic participation in the sport prior to the early sixteenth century requires explanation; particularly since there is evidence of Scottish and, to a lesser extent, English noblemen playing football thereafter. It cannot have been because indulging in sport demeaned authority. On the contrary, such activity may have served as an affirmation of physical prowess and as male bonding exercises – especially when played among peers. Nor can it have been because playing football might lead to injury: Henry VIII was involved in serious jousting accidents in March 1524 and January 1536, while hunting could also be exceedingly dangerous. Rather, it seems that football was frowned upon because it was generally regarded as a game for commoners. Hence in his discussion of the forms of physical exercise appropriate for young men being groomed for governance, the humanist and diplomat Sir Thomas Elyot (c.1490–1546) declared that football, along with skittles and quoits, was an utterly unsuitable recreation for noblemen. In addition, it may be that the unregulated nature of football contrasted markedly with the elaborate rituals associated with tournaments and hunting, not to mention the formalised nature of tennis with its structured passages of play and widely understood scoring system.

Away from the courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII, our next half-dozen examples concern the deaths of their subjects during ball games. Most of these references were uncovered by Steven Gunn, firstly in his work on archery and then his larger project on accidental death in sixteenth century England. Thus on Sunday, 20 February 1508 Thomas Bryan was playing ‘ffoteball’ at Yeovilton, Somerset when he inadvertently fell on his knife, which was hanging from his belt. The blade pierced his body and Bryan died immediately. The following year on Sunday, 4 February 1509 about sixty people gathered at Tregorden, Cornwall to play hurling according to the customary manner. Among them was John Coulyng who, holding a ball in his right hand, ran swiftly and strongly until he collided with Nicholas Jaane, labourer of Benboll. After a tussle Jaane threw Coulyng to the ground, breaking his left leg. Within three weeks Coulyng died from this injury at Bodieve, Cornwall. On Tuesday, 9 January 1515 Thomas Blyth of Barley, Hertfordshire accidently killed Andrew Royston with a sheathed knife while playing football; Blyth was pardoned six months later. Then on Sunday, 8 February 1523 William Merten, husbandman of Great Shelford, Cambridgeshire was playing football at Waterbeach on the common green when he was forcefully obstructed by William Hay, servant of a Cambridge brewer. Merten died as a consequence of his fall, prompting Hay to flee. Hay was apparently poor since the inquest recorded that he had no goods or chattels. Twelve days later on Friday, 20 February 1523 John Langbern of Allerston, Yorkshire was playing football with Roger Bridkirk, labourer, and many others. They both ran after the ‘foteball’ before crashing into each other. Roger fell on top of John and crushed him to death on the spot. Finally in August 1526 John Hasapote, joiner, and William Kynge, labourer, together with some boys and girls were playing handball (‘Cacche’) on the King’s Road in Wheatley, Oxfordshire. Hasapote fell on the ball and then Kynge fell on top of him, accidently wounding Hasapote in the right side of his body through to the heart with a knife that he had in his pouch.

The National Archives, KB 9/448/44, concerning the death of Thomas Bryan while playing at ‘ffoteball’ at Yeovilton, Somerset on Sunday, 20 February 1508