For two years now, one of my most impactful Twitter (now X) threads from around the Armistice Day period has been a series of simple images of artefacts associated with death and mourning during the First World War.[1] The interest in this thread is no doubt due to the power of artefacts, indeed of material culture in general, to make a direct connection between the observer and the originator. The Government’s commitment to the commemoration of the Centenary of the Great War in 2013-14 was predicated on local remembrance. Artefacts were a significant part of this. To quote from a Parliamentary debate at the time:

young people working in their communities to conserve, explore and share local heritage from the first world war, epitomised by yellowing photos of young men posing stiffly in uniform, possibly for the first and last time.[2]

Casualties in the Great War are strictly defined as those combatants who were no longer combat effective. This means that in addition to deaths there would not only be those who were wounded or sick – and therefore unable to fight – but also men who were missing or prisoners of war. There are a variety of ways of determining these losses, and as a consequence there is some variability in terms of the numbers that this brings. In general, though, there is an understanding that the percentage of men who were killed relative to those who joined was something like 11-12%, with twice as much again in terms of the numbers who were wounded. Therefore, the majority who joined were likely to have returned home.[3]

These figures could be said to hide the impact of deaths on certain communities and demographics. This is especially so when we consider that losses among frontline fighting troops and junior officers were noticeably higher than those who were never deployed overseas or who had ancillary or primarily non-combatant roles. Nevertheless, the widespread reporting of casualties in newspapers, and the establishment of ‘street shrines’ up and down the country fuelled the widespread recognition of loss. Surviving artefacts like those illustrated below help us to navigate a track of death and mourning to assist in our understanding of its scale and significance.

One question that is often asked is how families at home received news of the loss of their loved ones. One way could have been the return of a letter that had been written to the intended recipient in the understandable expectation that he would be living and breathing at the moment it was delivered to him. Were such a letter to be returned before official notification had been issued then it is feasible that this would have been the first indication of the death of the family member. Private Herbert Ashton, for example, had been in France since 14 September 1914. Although he was stationed in the transport section of his battalion (the 1st Norfolk Regiment), and therefore outside of the lines, he succumbed to wounds received in the Ypres Salient. Afterwards, Ashton was buried in Bedford House Cemetery. It is difficult to say whether his family received this returned letter first. But whether or not they did, its effect on his wife Maud and young child Nora would have been devastating.

The idea of the receipt of the telegram – accompanied by the dreaded knock on the front door by a boy dressed in a quasi-military post office uniform and mounted on a bicycle – is embedded in popular culture. There is no doubt that the receipt of the otherwise innocuous brown envelope with its statement, ‘No Charge for delivery’, would in normal times not herald a tragedy. But these were not normal times. Serjeant Lee, from Macclesfield, Cheshire, was an experienced soldier who had served in the South African War of 1900-02. He lost his life, killed in action, during the assault of the 46th (North Midland) Division that helped break the Hindenburg Line. Whether the success of this assault was enough to comfort his parents at home in the Midlands, or his American wife, is difficult to say. Though ‘the’ telegram has now achieved near legendary status, in many cases, if not most, the family would receive an equally ominous ‘On His Majesty’s Service’ envelope. This contained a ‘pro-forma’ letter with the heart-breaking gaps in its text filled with a soldier’s name.

Private Beaney of the 13th Gloucestershire Regiment (Forest of Dean Pioneers) was wounded on the Somme in 1916. His family was no doubt pleased that, although wounded, he was transferred back to England with a ‘Blighty Wound’ in his leg. That said, they were doubtless distressed at being unable to make the trip from County Durham to Gloucestershire, where he was being cared for in a military hospital. Nevertheless, his children sent him home-made Christmas cards and hoped he would recover. But Private Beaney succumbed to gangrene and died on 28 December 1916. His wife retained all letters of condolence from the nurses and staff of his military hospital in a child’s stiff card vest box. They were doubtless treasured, consulted to provide comfort. Yet this family still had to pay for the transport and burial of their husband and father in the cemetery at Silksworth, a burden on a working-class family.

That a soldier’s fallen remains on the battlefield would be identified if recovered was not guaranteed. Soldiers feared being forgotten. They still do today. Though British soldiers wore fibre identity discs – one to stay with the body, and one to be taken for ‘accounting’ purposes – they would not last once in the ground.[4] Often men would purchase additional, metal discs to wear as a bracelet, and would certainly mark their property with their names. This watch, marked ‘R.H. Purdie, 4th East Surrey’ to its rear, was sent back to the family of Robert Henry Purdie of the 2nd Leinster Regiment – an Irish battalion that he had been transferred into, to make up the shortfall in Irish recruiting. Purdie was killed on 12 April 1917, presumably during the Battle of Arras. It is safe to suggest that the remains of this battered watch would have had a material effect on the identification and burial of this fallen soldier.

With so many men serving overseas, maintaining a tangible connection with their loved ones was facilitated through mass photography. It was common for men to have ‘snaps’ taken of them in uniform - ‘the yellowing photographs’ referred to in planning for the UK Commemoration of the Great War Centenary. Faster lenses and more efficient photographic processes meant that such photos were easily produced in studios at camps and in town centres. Catering for the need for families to remain close to their ‘soldier boys’ meant that innovative means of creating keepsakes were invented. This silver brooch, for example, transforms into a miniature frame to permit the soldier to smile in perpetuity at the beholder.

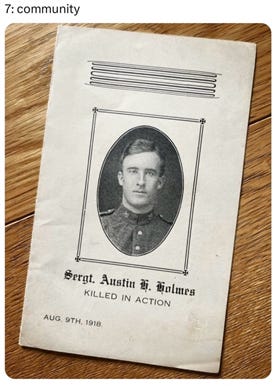

Twenty-two-year-old Austin Holway Holmes was serving with the 31st Battalion Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). He was killed in action the day after the opening of the ‘Battle of 100 Days’ that would hasten the end of the war. His family in New Brunswick saw fit to print a remembrance card for Serjeant Holmes, to serve as a reminder of their son who had lost his life in a foreign land, an ocean separating them. Shared in a community of grief, it survives to remind us of the youth of this citizen army, and of its sacrifice.

He whom this scroll commemorates was numbered amongst those who, at the call of King and Country, left all that was dear to them, endured hardness, faced danger, and finally passed out of the sight of men by the path of duty and self-sacrifice, giving up their own lives that others might live in freedom.

The sacrifice of almost one million men and women from the British Empire was not to go unmarked. Each next of kin would receive this scroll (its text suitably varied according to gender), alongside the bronze memorial plaque illustrated below. The issue of the scroll was announced in the press on 18 October 1917, each one hand inscribed in red ink.

The bronze memorial plaque was given to all men and women who died while part of the armed services and associated organisations, at home or overseas. The idea was conceived as far back as October 1916 and was a considerable commitment to the next of kin of those who had lost their lives. Each one was separately cast, not engraved. There are two ‘Frank Appleby’s’. So we cannot be certain who this was commemorating. They were treasured at the time. Indeed, there are frames for maintaining them and in some cases they were stuck to the deceased’s grave. Now often referred to in popular usage at the ‘death penny’, this terms perhaps hints at the notions of sacrifice and futility, ‘all for a penny’.

Loss of life was not restricted to one nation, and mourning not restricted to one culture. For German Catholic families, the issue of mourning cards with images of their soldier sons ‘gefallen für das vaterland’, together with patriotic messages, Christian imagery and religious verses was no doubt necessary to achieve some respite from losses that were keenly felt. The huge numbers that survive help illustrate the increasing losses experienced in the German army as the war ground on to its conclusion.

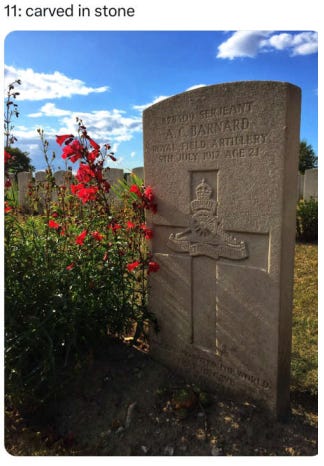

The Kenyon principles were drawn up by the Director of the British Museum, Sir Frederic Kenyon, and published in 1918.[5] These set out the ideals for the Imperial War Graves Commission. They were based on equality of treatment in death. They also insisted that there would be no repatriation of soldiers’ remains and no differentiation in death. As such, they were designed to ensure that soldiers from poorer social backgrounds would not receive any lesser recognition than those from more privileged families. It meant that many families would never get to see their soldier son’s graves, and that no special memorials could be erected to pick out any one soldier above another. Challenged at the time, these principles hold today. Serjeant Barnard of Bristol is buried in White House Cemetery. His inscription reads: ‘FOR GOD SO LOVED THE WORLD THAT HE GAVE HIS ONLY BEGOTTEN SON’.

Private Percy Edwards was just 18 years of age when he was mortally wounded in September 1918, during the last battles fought to push the Germans back over the 100 Days from August 8th. He was a ‘pit boy’ from Wales; i.e. as a boy he had worked long hours in a Welsh coalmine. And as a ‘pit boy’ he was therefore not unused to danger and death. Even so, he was a lad whose life was extinguished after just a few weeks at the front. His story is told in ‘Percy, A Story of 1918’ a tale that is read today in the two primary schools in the North Wales village of Cefn Mawr.[6] His name is inscribed upon the village Cenotaph. He, like so many of his generation that fell in the Great War, is not forgotten. Rather, they are remembered.

[1] https://x.com/ProfPeterDoyle/status/1572117283652374530

[2] Hansard, 7 November 2013, Column 484 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmhansrd/cm131107/debtext/131107-0003.htm

[3] See for example https://shs.cairn.info/article/E_POPSOC_510_0001?lang=en

[4] Sarah Ashbridge, https://doi.org/10.25602/GOLD.bjmh.v6i1.1359

[5] https://www.cwgc.org/media/qvylruql/the-kenyon-report.pdf

[6] Peter Doyle, Percy: a Story of 1918. London: Unicorn, 2018

War is such a sad event and so difficult for everyone involved. I hope and pray that we don't forget the sacrifices of the lives that were given to pay the price of freedom.