As far as I am aware, it has not previously been noted that a text by the Digger leader Gerrard Winstanley (1609–1676) was translated from English into a foreign language during the seventeenth century. This relatively brief post is about a Dutch manuscript version of Winstanley’s The New Law of Righteousnes (London: Giles Calvert, 1649).

Entitled ‘Nieuwe Wet der Gerechtigheyt’ and described as being in octavo, the work was listed in the library catalogue of Petrus Serrarius (1600–1669). Most likely this was a unique manuscript since I have yet to find reference to a copy elsewhere. Furthermore, because – to the best of my knowledge – this Dutch version has never come to light, it may no longer be extant. But as we shall see, it does appear that the translator was probably Serrarius himself. For although Serrarius’s ownership of Winstanley’s New Law of Righteousnes is unrecorded there is no reason to doubt either that he had once possessed a copy or else had borrowed it. Indeed, Serrarius’s interest in Winstanley’s writings is confirmed by another entry in his library catalogue: Winstanley’s The Mysterie of God (London: Giles Calvert, 1649).

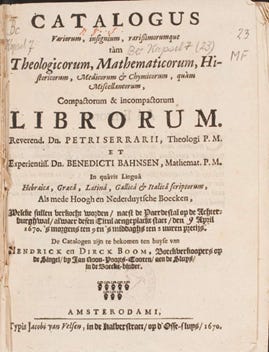

Catalogus Variorum, insignium, rarißimorumque tàm Theologicorum, Mathematicorum, Historicorum, Medicorum & Chymicorum, quàm Miscellaneorum, Compactorum & incompactorum Librorum. Reverend. Dn. Petri Serrarii, Theologi P.M. Et Benedicti Bahnsen (Amsterdam, 1670) [Herzog August Bibliothek (Wolfenbüttel), M: Bc Kapsel 7 (23)]

So who was Serrarius? The son of an affluent Walloon merchant, he was born in London and baptized at the French Church in Threadneedle Street on 11 May 1600. He matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford in November 1617 and then studied theology at the Walloon seminary in Leiden, where he remained until 1623. Afterwards he matriculated at Leiden University in May 1624. In June 1626 Serrarius succeeded the Edinburgh-born John Dury (1596–1680) as minister of the secret Walloon Church (‘du Verger’) in Cologne. Serrarius, however, was subsequently suspected of an unspecified disciplinary error and removed by the Walloon synod after less than two years. Although the evidence is retrospective, it has been suggested that he had imprudently expressed heterodox opinions – variously thought to be the ‘fanatical errors’ of the German Spiritualist Reformer Caspar Schwenckfeld (1490–1561); millenarian beliefs; enthusiasm for mystical theology; or rejecting the notion that Christ had assumed human nature. Thereafter Serrarius studied medicine at Groningen University, where he matriculated on 9/19 December 1628. But by September 1629 Serrarius had abandoned his formal medical studies and settled at Amsterdam. There he developed an interest in alchemy, married Sara Paul van Offenbach in 1630 and obtained work as a proofreader for the publisher Johann Janssonius (1588–1664). Apart from intermittent trips to England, Serrarius would reside at Amsterdam for the remainder of his life, living near the Westerkerk on Prinsengracht next to a brewery at ‘The Red Heart’ in later years.

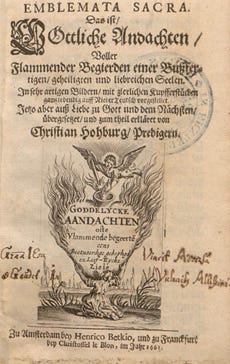

Petrus Serrarius, Emblemata sacra (Amsterdam and Frankfurt, , 1661)

The multi-lingual author of about twenty titles issued in a variety of European languages (Latin, Dutch, French, German and English), Serrarius has been the subject of several modern scholarly studies in Dutch, French and English – notably articles and book chapters by K. Meeuwesse, J. van den Berg and Ernestine van der Wall, as well as an unpublished dissertation by van der Wall. Their research has emphasised Serrarius’s interest in a number of Catholic and Protestant mystics, particularly Johannes Tauler (c.1300–1361), Thomas à Kempis (d.1471), Denis the Carthusian (1402–1471), John of the Cross (1542–1591), Jacob Boehme (c.1575–1624) and Antoinette Bourignon (1616–1680). He was also a firm believer in Christ’s imminent return and thousand-year reign on earth, justifying his chiliasm through interpretations of key scriptural passages and astrological conjunctions. In addition, Serrarius outlined his views on freewill and predestination, indicated his differences with the Quakers in some pamphlets, met Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel (1604–1657), knew Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) and devoted a great deal of time to circulating reports concerning actual and fabricated exploits of the Jewish pseudo-messiah Sabbatai Sevi (1626–1676).

Besides his preoccupation with alchemical medicine, mysticism, millenarianism, Quakers and Jews, Serrarius had a transnational epistolary network. Among those sometime resident in England with whom he corresponded were the preacher and ecumenist John Dury, the alchemist and scribe Theodoricus Gravius (c.1600–fl.1658), the nonconformist minister Henry Jessey (1601–1663), the Independent ministers Joshua Sprigge (1618–1684) and Nathaniel Homes (1599–1678), the Seeker John Jackson (fl.1660), the Royal Society secretary Henry Oldenburg (c.1618–1677), the educational reformer and intelligencer Samuel Hartlib (c.1600–1662), the visionary Sarah Wight (fl.1647) and an unknown lady (possibly Katherine, wife of the Dutch drainage engineer Sir Cornelius Vermuyden or their daughter Sara). Doubtless these extensive contacts enabled Serrarius to access a wide variety of texts and he put his linguistic talents to use by translating more than ten works from Latin, German and English into Dutch. Serrarius’s earliest published translation was an edition of Tauler’s works from the German (Hoorn, 1647) and afterwards he rendered several titles from English into Dutch by Jessey, Sprigge and Wight, as well as by the Quaker William Dewsbury (c.1621–1688), the Parliamentarian army officer Robert Wilkinson (fl.1655) and the minister Richard Lanceter (1604–fl.1660). His last published translations were works by the former Jesuit Jean de Labadie (1610–1674) and the Moravian pedagogue Johannes Amos Comenius (1592–1670).

Together with Serrarius’s ownership of about sixty printed English works, including several by Jacob Boehme and Nathaniel Homes, his known choices as a translator indicate that he was probably also responsible for turning Winstanley’s New Law of Righteousnes into Dutch. Since the preface of The New Law of Righteousnes was dated 26 January 1649 and since Serrarius was buried at Amsterdam on 21 September / 1 October 1669, the Dutch translation was certainly completed between these dates. However, if Serrarius merely acquired a Dutch version of Winstanley then a plausible alternative translator was the Colchester-born Quaker merchant and bibliophile Benjamin Furly (1636–1714). Having initially travelled to Amsterdam where he attended a meeting of the Mennonite Collegiants at Serrarius’s home on 14/24 August 1660, Furly afterwards settled at Rotterdam. Furly was the author of several printed works, the earliest dated 1662, while his first printed translation from English into Dutch was issued in 1665. At the time of his death he had assembled a huge private library containing about 4,300 titles – including works by Serrarius, as well as The True Levellers Standard Advanced (London, 1649) and ‘other treatises’ by Winstanley.

Bibliotheca Furliana (Rotterdam, 1714)

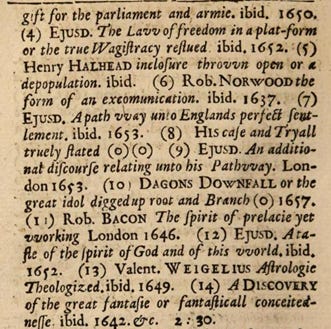

Many of Furly’s books passed into the hands of a visitor to his library, Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach (1683–1734), so it is possible to guess what these ‘other treatises’ may have been from von Uffenbach’s more detailed library catalogue. Besides The True Levellers Standard Advanced, these were listed as Winstanley’s A Watch-word to The City of London, and the Armie (London: Giles Calvert, 1649), A New-yeers Gift for the Parliament and Armie (London: Giles Calvert, 1650), and The Law of Freedom in a Platform (London: Giles Calvert, 1652).

Bibliotheca Uffenbachiana (4 vols., Frankfurt, 1729–31)

Yet regardless of whether the translator was Serrarius, Furly or someone else, the intended audience for ‘Nieuwe Wet der Gerechtigheyt’ remains unclear. Given the labour involved it was doubtless intended for circulation. But whether this was envisaged for a small group of acquaintances, perhaps facilitated through scribal publication, or a much larger community through the medium of print, is uncertain. If it had been intended for publication perhaps financial constraints or lack of interest meant it never saw the light of day. Finally, it should be stressed that both The New Law of Righteousnes and The Mysterie of God were among Winstanley’s five earliest books. These were reprinted collectively as Several Pieces Gathered into one Volume (London: Giles Calvert, 1649). Accordingly, they pre-date Winstanley’s digging activities. So we can only speculate as to whether Serrarius was aware of the Diggers. But given what we know about this multi-lingual millenarian, his range of associates, extensive correspondence network and voluminous reading habits, this seems likely

.

Fascinating. These networks make me wonder whether tendency to lump by emerging denominational networks within these islands is becoming just a bit too parochial! Another great article.