‘In this house I chanced to find a volume of the works of Cornelius Agrippa. I opened it with apathy; the theory which he attempts to demonstrate and the wonderful facts which he relates soon changed this feeling into enthusiasm. A new light seemed to dawn upon my mind, and, bounding with joy, I communicated my discovery to my father. My father looked carelessly at the title page of my book and said, “Ah! Cornelius Agrippa! My dear Victor, do not waste your time upon this; it is sad trash.”’ [Mary Shelley, Frankenstein or, The modern Prometheus (1818), chapter 2]

A peripatetic Renaissance humanist, linguist, lawyer, physician, alchemist, soldier and author, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535?) is best known for several learned treatises including an exaltation of the virtues of women, an exposition of the vanity of arts and sciences, and an infamous compendium of magical lore known as De occulta philosophia sive magia libri tres (Cologne, 1533). These three books of occult philosophy show great erudition and a familiarity with Latin texts. Moreover, they were instrumental in shaping Agrippa’s largely tarnished reputation. For it was as a semi-legendary omniscient magus accompanied by a devilish black dog, indeed as a cautionary figure resembling the tragic Doctor Faustus, that he was largely known to early modern English readers.

Engraved portrait of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa in an edition of his complete works probably published at Strasbourg about 1600

Following Agrippa’s death, published versions and manuscript copies of his writings circulated widely throughout Europe in a variety of languages among Christians and a handful of Jews between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries – particularly in England, France, German-speaking areas, the Italian peninsula, the Netherlands and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. They influenced views about the Reformation, scepticism, melancholy, music, physiognomy, angels, witchcraft, magic, numerology, Kabbalah and Hermeticism. In addition, Agrippa was a prolific correspondent and a number of his letters fortunately survive. These were posthumously published in a two volume edition of his collected works probably issued at Strasbourg about 1600 (rather than Lyon as the imprint suggests). Also included in Agrippa’s Opera omnia was a Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy. Although this reinforced contemporary perceptions of Agrippa as a diabolic necromancer it was almost certainly a spurious compilation.

So who was Agrippa? The son of Henry (d.1519), who styled himself of Nettesheim, he was probably born in 1486 (sixteenth-century biographers commonly stated on 14 September). Most likely this was at Cologne since he would adopt part of the Latin name for that city – Colonia Agrippina – as his surname. Although it was claimed that Agrippa came from a ‘noble and ancient’ family, indeed that they had a long history of service to the Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg, this may have been an exaggeration to gain patronage. As for his education, Agrippa matriculated at the Arts Faculty at Cologne University on 22 July 1499. Among the books he read were probably works by the Dominicans Thomas Aquinas (c.1225–1274) and Albertus Magnus (c.1200–1280), as well as Pliny the Elder’s Natural History and Ramon Lull’s Ars brevis. After graduating in March 1502 Agrippa disappears almost without trace for five years. But by late March 1507 he was studying at Paris. About 1508 he undertook a journey to Spain by way of Avignon, perhaps to participate in a military expedition.

In 1509 Agrippa lectured on De verbo mirifico (Basel, 1494) by the Christian Kabbalist Johann Reuchlin (1455–1522) at the University of Dôle in Burgundy. About the same time he also wrote a brief treatise on the ‘glory’ of women and their accomplishments for that ‘most wise princess’ Margaret of Austria (1480–1530), Duchess of Savoy and Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands. Entitled ‘De nobilitate et praecellentia foeminei sexus’ [On the nobility and pre-eminence of the female sex] (1509), Agrippa drew primarily upon biblical and classical sources to provide a number of examples supporting his argument. All the same it would be nearly twenty years before Agrippa presented his treatise to Margaret. This is because despite the support of Antoine de Vergy, Archbishop of Besançon and chancellor of the University of Dôle, Agrippa was denounced in a sermon preached by the Franciscan Jean Catilinet at the court of Flanders in Ghent. According to Agrippa, Catilinet accused him of being:

a judaizing heretic, who introduced into Christian schools the criminal, condemned and prohibited art of Kabbalah, who, despising the Holy Fathers and Catholic doctors, prefers the rabbis of the Jews, and bends sacred letters to heretical arts and the Talmud of the Jews.

The following year Agrippa was briefly in London where he became acquainted with the ‘learned and virtuous’ humanist John Colet (1467–1519), an expert on Pauline theology, and Thomas Cranmer (1489–1556), a future Protestant reformer and Archbishop of Canterbury. That same year Agrippa dedicated the manuscript of his treatise ‘De occulta philosophia’ to the Benedictine Abbot Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516), ‘a man very industrious after secret things’, who received it at the monastery of St. Jakob, Würzburg before 8 April 1510. Trithemius, however, counselled Agrippa to read more deeply on these topics and take care in how he chose to reveal them:

But this one thing let me warn you, speak of things public to the public, but of things lofty and secret only to the most private of your friends. Hay to the ox, sugar to the parrot – rightly interpret this, lest you, as some others have been, be trampled down by oxen.

Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516)

From about 1511 until early 1518 Agrippa was mainly in the Italian peninsula. During this time he was in the service of Maximilian I (1459–1519) the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor. Probably he was a soldier, since Agrippa claimed that he was awarded a knighthood for valour on the battlefield:

Before me stalked Death; I followed, Death’s squire. My right hand was ready to shed blood, my left hand divided the spoils. I sated my belly with plunder, and my steps were over the bodies of men butchered.

Albrecht Dürer ‘Knight, Death, and the Devil’ (1513)

On 12 July 1513, moreover, Agrippa was commended for his zeal to the new Pope Leo X (1475–1521). By this time Agrippa had begun lecturing at the University of Pavia, where in 1515 he declaimed upon the Pimander attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. It was also at Pavia that Agrippa met a ‘well behaved and beautiful’ unnamed young lady of good family. This ‘affectionate, affable’, ‘honest’ and ‘prudent’ woman became his first wife and by March 1517 they had a son.

Eustace Chapuys (d.1556)

Two years previously Agrippa had lectured at Turin in the Duchy of Savoy, perhaps on the Pauline Epistles. Among his auditors was Eustace Chapuys (d.1556) who would become a friend, correspondent and reader – not to mention the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s ambassador to England. It was probably during this period between 1515 and 1517 that Agrippa wrote an undated oration on Plato’s Symposium. In addition, Agrippa dedicated two works to his patron William IX Palaeologus (1486–1518), Marquis of Montferrat [Piedmont]. These were the unfinished ‘Dialogus de homine’ [Dialogue on man] (1515–16) and ‘De triplici ratione cognoscendi Deum’ (1516). The latter was a lengthy treatise on the threefold way of knowing God through nature, the Law of Moses and Jesus Christ. It included a defence of devotees of the ‘ancient theology’, who had been scorned as ‘madmen, ignorant, irreligious’ and ‘sometimes even heretics’. A further treatise ‘De originali peccato’ [On original sin] (1518?) concerned the apprehension of religious truth through faith rather than reason, although some readers were shocked by Agrippa’s unorthodox contention that original sin had begun with Adam and Eve’s copulation.

Erasmus of Rotterdam (c.1466–1536)

From 1518 to 1520 Agrippa resided at the free imperial city of Metz, where he was employed as advocate and orator. While at Metz, Agrippa defended an old peasant woman who had been accused of witchcraft by a Dominican Inquisitor. By his own account, Agrippa secured her release by focusing on the irregular legal proceedings in the case. Another controversy concerned the monogamy of St Anne, fabled mother of the Virgin Mary and, as related in The Golden Legend, supposedly wife to three husbands – Joachim, Cleophas and Salome. This led to Agrippa corresponding with the leading French humanist Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (c.1455–c.1536), who urged Agrippa to avoid controversy. And with good reason since Agrippa was now reading works by Erasmus of Rotterdam (c.1466–1536) and Martin Luther (1483–1546). Indeed, among Agrippa’s acquaintances at Metz were a Celestine monk who would abandon his faith to become a Reformed pastor and a bookseller who would be exiled for Lutheran beliefs. All the same, Agrippa departed Metz, ‘stepmother of all arts and sciences’, before the spread of Lutheranism exacerbated pre-existing political and religious tensions.

By mid-February 1520 Agrippa had returned to Cologne, where he pursued his scholarly interest in ancient wisdom, magic and the St Anne controversy. The following year he went back to Metz where his wife sickened, died and was buried. From Metz Agrippa journeyed to Geneva, arriving in spring 1521. There he married again. His second wife was likewise a ‘very beautiful’ obedient young lady of ‘a good family’. Her name was Latinized as ‘Iana Loysa Tytia’ (c.1503–1529) and the couple had one daughter (died young) as well as five sons, three of whom – Aymon, Henry and Jean – survived their father. As one modern authority has stressed, Agrippa’s friends at Geneva were ‘no crypto-Protestants’. Rather, they included people like Eustace Chapuys, then serving as the local bishop’s agent, and Aymon de Gingins, Abbot of Bonmont. It was doubtless through their support that on 11 July 1522 the ‘honourable lord’ Agrippa, ‘doctor of arts and medicine, from Cologne on the Rhine’ was granted citizenship. Among Agrippa’s duties was care of the city’s sick and destitute, although he complained about lack of money.

Marguerite d’Alençon (1492–1549), afterwards Queen of Navarre

Agrippa stayed at Geneva until roughly the beginning of 1523. Then he went to Fribourg, arriving sometime in March and remaining until spring 1524. During this time Agrippa was employed as the town’s physician. But he bemoaned that the place was ‘bare and destitute of the cultivation of all sciences’. The civic authorities, moreover, actively suppressed the spread of Lutheranism. So Agrippa departed. By the spring of 1524 he was in Lyon, where he would remain until early December 1527. Among Agrippa’s circle at this time were likely some wealthy and influential aristocrats, including members of the Laurencin family, as well as fellow physicians and local officials. In addition, Agrippa dedicated a work to Marguerite d’Alençon (1492–1549), sister to King Francis I of France (1494–1547) and afterwards Queen of Navarre. Entitled ‘De sacramento matrimonii’ [On the sacrament of marriage] (spring 1526), here Agrippa argued that adultery was grounds for divorce.

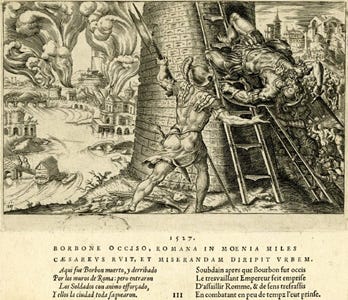

Nonetheless, Agrippa quickly fell out of favour at the court of Louise de Savoy (1476–1531), mother of Francis I of France. Besides bitter complaints that he was not being paid money that had been promised to him, the main cause of Agrippa’s disgrace seems to have been his refusal to draw up a horoscope for Francis. Instead, he foolishly prognosticated Francis’s impending death and the good fortune of the French king’s principal rival Charles III, Duke of Bourbon (1490–1527). Consequently, Agrippa was suspected of favouring the Bourbon cause. Nor was the charge without foundation since Agrippa corresponded with the Duke, even foretelling the ‘glorious’ military triumph that awaited this ‘most valiant prince’. The Duke, however, was killed leading mutinous troops of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V during the sack of Rome in 1527.

Martin van Heemskerck, ‘The sack of Rome’ (1527)

During this time Agrippa completed two important works. One was ‘Dehortatio gentilis theologiae’ [A dissuasion against pagan theology] (June 1526) dedicated to Symphorien Bullioud (1480–1533), Bishop of Bazas. The other was ‘De Incertitudine et Vanitate Scientiarum’ [On the Uncertainty and Vanity of Sciences] (late summer 1526), described by one modern scholar as ‘a biting critique of human science’, ‘a ferocious and radical attack on the moral and social assumptions of his day’.

Upon leaving Lyon, Agrippa made his way to Paris where he resided from December 1527 to July 1528. From there he went to Antwerp where he engaged in medicine, alchemy and astrology. During an outbreak of summer plague Agrippa claims to have cared for the sick. His wife, however, debilitated after giving birth to a son, died of plague at Antwerp on 17 August 1529 while several of the family’s servants also succumbed. Agrippa lamented her passing in a letter:

I am lost for I have lost her who was the only solace of my life, the sweetest consolation of my labours, my most loved wife. Ah, she is lost to me and dead, but eternal glory covers her. She is dead, to my greatest sorrow, to my greatest hurt, to the greatest disadvantage of our children.

In 1529 Agrippa received invitations to attend various courts and retinues, namely that of Henry VIII of England; Mercurino Gattinara (1465–1530), the imperial chancellor; an Italian aristocrat; and Margaret of Austria. Having accepted Margaret’s offer he was appointed imperial archivist and historiographer on 27 December 1529. Among Agrippa’s writings while occupying this post were an account of Charles V’s double coronation at Bologna (1530), a welcoming speech, and Margaret’s funeral oration following her death at Mechelen in December 1530.

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, De nobilitate et praecellentia foeminei sexus [On the nobility and pre-eminence of the female sex] (1532)

It was also in 1529 that Agrippa published his treatise on the glory of women. Dedicated to Margaret, it was printed at Antwerp along with some smaller works in a single volume issued by Michael Hillenius. At Antwerp, moreover, Agrippa secured the imperial privilege for his longer works, notably De Vanitate Scientiarum (press of Johannes Graphaeus, 1530) and the first book of an expanded version of De Occulta Philosophia (Johannes Graphaeus, 1531), dedicated to the Archbishop-Elector of Cologne, Hermann von Wied (1477–1552). The theologians of Louvain, however, condemned the De Vanitate Scientiarum as scandalous, impious and heretical, while the Sorbonne denounced it in similar terms. Yet Agrippa refused to recant, instead penning two defences. One of these complaints against slander was dedicated to Eustace Chapuys, who had urged Agrippa to write in defence of Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536) in the great matter of Henry VIII’s divorce.[1] The controversy over De Vanitate also brought him to Erasmus’s attention, who counselled against antagonising the ecclesiastical orders. Nonetheless, in September 1532 Agrippa wrote to the German reformer Philip Melanchthon (1497–1560) asking him to send greetings to ‘that unconquered heretic Martin Luther, who, as Paul says in Acts, serves God according to the sect they call heresy’.

Following a brief period of imprisonment for debt at Brussels and then a visit to Cologne in March 1532, Agrippa began preparing a complete three volume version of De Occulta Philosophia for the press. Although the work was denounced as heretical doctrine by the Dominican inquisitor, Conrad Colyn of Ulm, Agrippa eventually secured publication through the intercession of his patron the Archbishop of Cologne. Accordingly this text was issued at Cologne in July 1533 by Johannes Soter, but prudently without a printer’s name and the place of publication.

The last two years of Agrippa’s life are obscure. He was at Bonn in November 1532 and Frankfurt in April 1533 before returning to Bonn. There in 1535 he was said to have divorced his third wife, a woman otherwise unknown except that she was from Mechelen. Sometime in 1535 Agrippa went back to Lyon. At Lyon, according to the account of his former student Johann Weyer (1515–1588), Agrippa was arrested on the orders of Francis I for derogatory remarks concerning Francis’s deceased mother Louise de Savoy. Agrippa, however, was soon released on the intercession of his supporters. Agrippa apparently died in extreme poverty at Grenoble, possibly at the city’s hospital or else the house of a government official. Most likely this was in 1535 or perhaps 1536. He was reportedly buried at the Dominican convent in Grenoble. Three sons survived him.

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Van de Onzekerheid en Ydelheid der Wetenschappen en Konsten [On the Uncertainty and Vanity of Arts and Sciences] (Rotterdam, 1661)

[1] Agrippa alluded to the matter in De Vanitate: ‘I am informed, there is a certain King, at this time of day, who is persuaded, that it is lawful for him to divorce a wife, to whom he has been married these twenty years, and espouse an harlot’.

Great words🤗🤗

Thank you for this clearly written essay. I have also been enjoying Anthony Grafton's recent Magus: The Art of Magic from Faustus to Agrippa, which usefully describes the contents of Agrippa's vast work.