Before I begin, I want to briefly recap some conclusions from the previous part. We have seen that there were a number of individuals of Jewish birth or origin who were present in England between the Expulsion of 1290 and the accession of the Tudor dynasty in 1485. This was partly because conversion from Judaism to Christianity ensured shelter and occasionally brought financial reward, status and security. Jewish physicians, moreover, seem to have been highly valued. Yet as we shall see, small-scale Jewish emigration to England was not only economically motivated but sometimes an act of desperation.

IV. The Tudor period

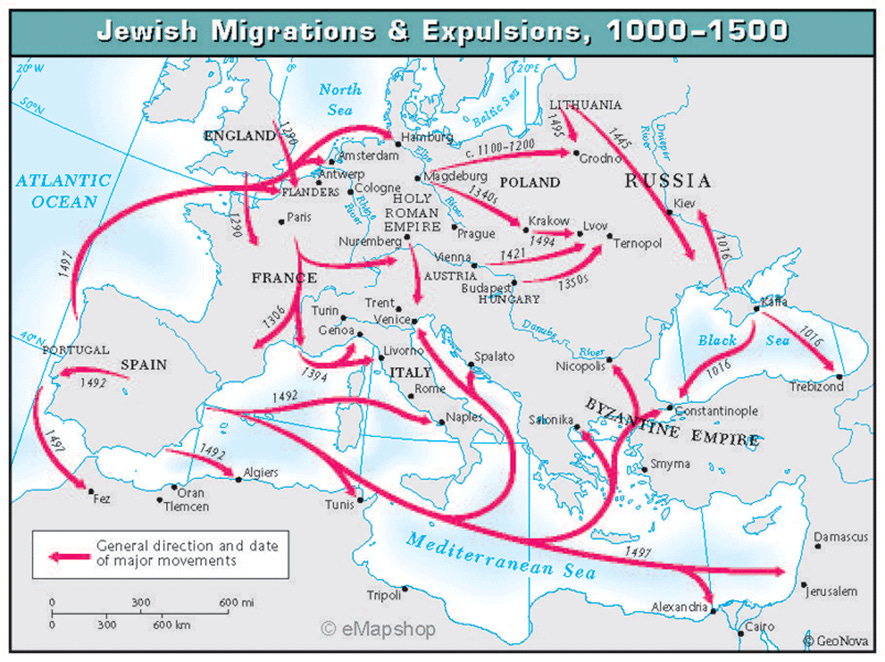

Having been expelled from France in 1182, 1306, 1311, 1327 and 1394, from Gascony in 1287, Anjou and Maine in 1289, not to mention England in 1290, Jews continued to be expelled from many parts of Europe and indeed European colonies during the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Miniature from the Grande chronique de France depicting the expulsion of the Jews from France in 1182 (they were readmitted in 1198)

Thus Jews were expelled from parts of the Italian Peninsula – Perugia in 1485, Vicenza in 1486, Parma in 1488, Lucca and Milan in 1489, Florence in 1494, and Naples in 1496; from Mediterranean Islands – Sardinia and Sicily in 1492; from Provence in 1498; and from Iberian soil – Castile and Aragon in 1492, Portugal in 1497, and Navarre in 1498. The majority fled and over roughly the next century and a half dispersed to North Africa (Cairo, Ceuta, Fez, Larache, Orán [expelled 1669], Tangiers, Tlemcen, Tunis); the Balearic Islands (Ibiza, Majorca); the Aegean Islands (Crete, Rhodes); France (Bayonne, Bordeaux, Montpellier, Nantes, Rouen, Toulouse); the Netherlands (Amsterdam, Antwerp); the Italian States (Ancona, Ferrara, Livorno, Mantua, Ragusa, Rome, Turin, Venice); Bohemia (Prague); Poland; the Ottoman Empire (Morocco, Adrianople, Constantinople, Gaza, Hebron, Jerusalem, Safed, Salonika, Tiberius); India (Bombay, Cochin, Goa, Ormuz); the East Atlantic Islands (Canary Islands); West Africa (Senegal); the Caribbean (Barbados, Curaçao, Jamaica); North America (New Amsterdam); Mexico (Acapulco, Campeche, Mexico City, Veracruz); Brazil (Bahia, Pernambuco [expelled 1654]); Surinam; and Peru.

Among the few Jews of this early-modern diaspora who made their way to England were several unnamed Spaniards, and Elizabeth of Portugal, who was admitted to the Domus Conversorum in 1492. Others may have reached Ireland for it was claimed that a physician named Fernandes had been born there. He has been identified with Pedro Fernandes, a successful London medical practitioner. Besides these individual instances, Jews participated in a significant episode of English history as advocates of Henry VIII’s divorce. Hence from 1530 Italians with Jewish backgrounds such as the rabbi, physician and Kabbalist Elijha Menahem Halfan and particularly the Venetian convert to Christianity Marco Raphael, were consulted by the King’s solicitor in an effort to prove from Leviticus that Henry’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon – the widow of his brother Arthur – had been unlawful.

Further European events also played a part in bringing Jews to England. Thus it has been estimated that between 1388 and 1520 more than ninety German-speaking towns, cities and territories – including Linz (1421), Vienna (1421), Cologne (1424), Dresden (1430), Speyer (1435), Augsburg (1440), Bavaria (1442, 1450), Erfurt (1458), Mainz (1470), Bamberg (1478), Würzburg, (1488), Heilbronn (1490), Mecklenburg (1492), Pomerania (1492), Halle (1493), Magdeburg (1493), Lower Austria (1496), Carinthia (1496), Styria (1496), Nuremberg (1499), Ulm (1499), and Regensburg (1519) – expelled Jews.

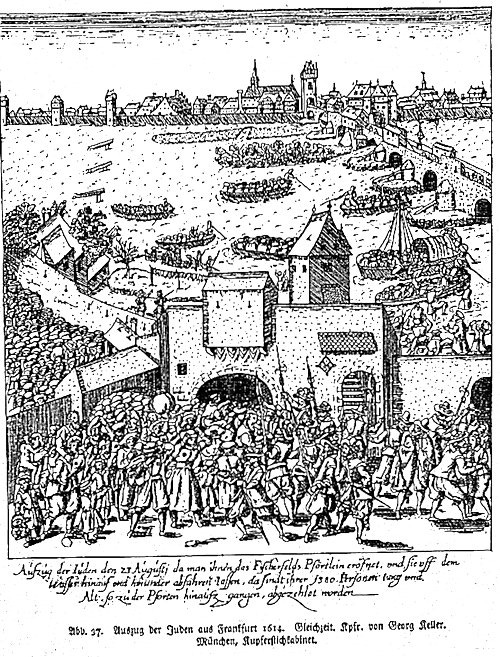

The expulsion of Jews from Frankfurt in 1614 following anti-Jewish riots; according to the text, 1,380 Jews were forced to leave the city.

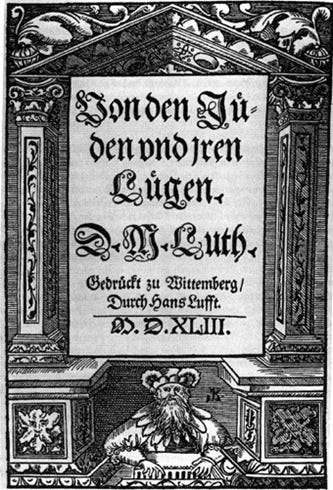

Moreover, Johann Gutenberg’s invention of movable printing type enabled the enemies of Judaism to mass-produce well-known anti-Jewish libels and circulate them to larger audiences than ever before. Among the most fanatical of these pamphleteers were Ulrich Zasius, a professor of civil law, and the apostate Johannes Pfefferkorn. Zasius defended the forced baptism of Jewish children and advised Christian princes to expel Jews from their territories. Pfefferkorn attacked supposed Jewish blasphemies, proposed confiscating all Hebrew books except the Scriptures, burning the Talmud and converting Jews.

Johannes Pfefferkorn (1469-1521)

In the same vein, Johannes Eck, a professor of theology and leading defender of the Papacy, repeated allegations of Jewish ritual murder claiming to have placed his own fingers in the wounds of a child killed by Jews. He even denounced Jew-lovers as products of the Reformation.

Alleged ritual murder of Simon of Trent (d.1475) from the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

This was certainly inaccurate for Martin Luther, who had hoped to convert Jews to a purified church, caught the vicious mood as well. He wrote a bitter tract On the Jews and their Lies (1543) and preached a sermon against those ‘miserable and accursed people’ the day before his death.

Among the exceptions to these waves of German anti-Jewish sentiment was Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, who supported several proposals for tolerating Jews in Kassel, even rejecting advice from Protestant theologians like Martin Bucer on the matter. Afterwards the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V not only condemned ritual murder trials but reaffirmed previous imperial and papal privileges granted to Jews, placing all Jews in the Holy Roman Empire under his personal protection.

The picture in Iberia was even grimmer. Spanish poets from the twelfth to the fifteenth century had generally depicted Jews negatively as avaricious, treacherous deicides, combining these conventional racial slurs with an emphasis on the strangeness of Jewish laws and customs. In 1391 the Jewish quarters of Castilian and Aragonese cities were sacked, their inhabitants massacred and survivors forced to convert to Christianity. Known variously as conversos (Spanish for turncoats or converts), judaizantes (secret Jews), marranos (probably derived from the Arabic term for stranger and meaning pigs or swine in Spanish), or Cristãos novos (New Christians), they were permitted to take up public office and with time a number became prominent in the royal administrations of Castile and Aragon. Though wealthy New Christian families intermarried with the Castilian nobility the sincerity of their new-found beliefs was soon questioned by Old Christians. This resentment became violent and atrocities were perpetrated against New Christians at Toledo (1449, 1467), Sepúlveda (1468), Córdoba (1473), Jaén (1473), Montoro (1473), Segovia (1474), and Valladolid (1474). To prevent New Christians from reverting to Judaism the Inquisition was established in Castile in 1478. Although Jewish sources, particularly rabbinic documents – which were mainly concerned with questions of marriage and inheritance of property – tended to regard New Christians as willing apostates rather than forced converts, the earliest phase of the Spanish Inquisition was clearly directed against them.

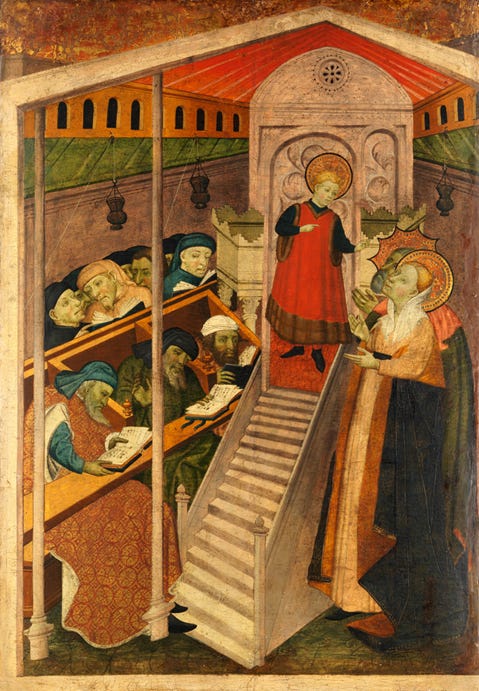

Christ among the 'doctors’; Jewish men seated in a contemporary Spanish synagogue, not the Jerusalem Temple (early 15th century)

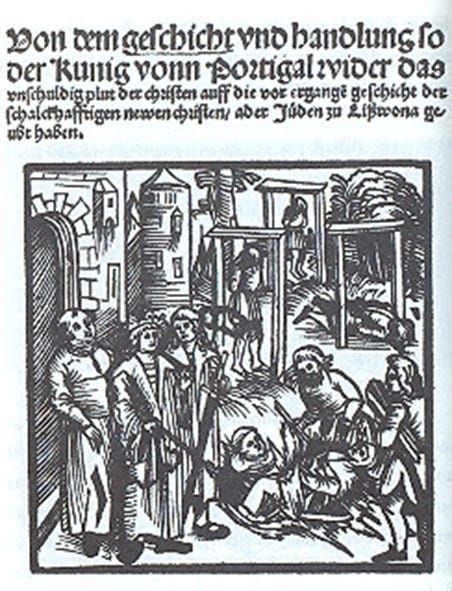

In Portugal, by contrast, there were comparatively few New Christians until 1497 when the remnant of Portuguese Jewry was baptized en masse. However, following an inflammatory sermon preached at Lisbon by a Dominican on Easter Sunday 1506 more than 2,000 New Christians were massacred over several days and their bodies, according to a contemporary chronicle, burned on a bonfire.

German woodcut depicting the massacre of New Christians at Lisbon in 1506. To quote the chronicler Damião de Gois, ‘they began to kill all the New Christians they found in the streets. They threw the dead and dying bodies onto … a bonfire, which they had made … In this business they were helped by slaves and serving-lads’

New Christians were later accused of causing an earthquake and their situation became even more dangerous in 1536 when Pope Paul III relented to political pressure and issued a bull establishing the Inquisition in Portugal. That same year Charles V granted New Christians permission to settle in the Netherlands. Although the Inquisition had already been established there, its principal target was Lutherans rather than crypto-Jews. Overcoming the difficulties of emigrating from Portugal, where their property was liable for confiscation, some New Christians eventually reached Antwerp. Others, however, were either detained by customs officials or interrogated at Middelburg. In 1541 two New Christians were burned alive there for refusing to accept that Christ had been crucified by Jews. The religious beliefs of the new arrivals at Antwerp were also investigated and an Imperial decree issued preventing further Portuguese immigration. Despite sixty-five arrests and a hastily rescinded Imperial order of 1549 declaring all recent Portuguese New Christian immigrants impenitent Judaizers, there were an estimated 800–900 Portuguese New Christians living at Antwerp by the mid-sixteenth century.

Among the earliest New Christian settlers in Antwerp was a merchant named Diogo Mendes (Bemveniste), whose extremely wealthy elder brother Francisco was a key member of a consortium that had purchased the rights to import pepper and spices from the Indies to Portugal. In 1537 Francisco Mendes’s widow Beatriz de Luna (the future Grácia Nasci) together with her daughter, sister and two nephews departed Lisbon on an English ship bound for London. Eventually they sailed to Antwerp, arriving by late February 1538. Judging from this and other incidents there seems to have been an organized network for transporting Portuguese New Christian refugees to the Netherlands. Using the spice trade as cover they headed initially to an English port where they awaited news of the situation at their destination. If this was unfavourable they usually disembarked at Southampton and then proceeded to London.

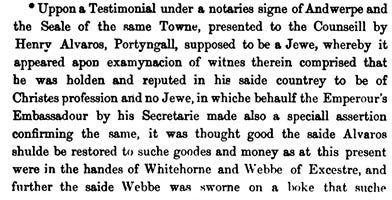

While the length of their stay varied, we know of several New Christian merchants and physicians resident in England during Henry VIII’s reign. Nor was the Crown blind to their presence for about Christmas 1541 ‘certayne parsons suspectid to be Jues’ were apprehended and their goods inventoried. The Imperial ambassador observed that even if they fully confessed, their freedom would come at a price. During the investigation the prisoners appealed to João III of Portugal and Maria, Regent of the Netherlands, who interceded with Charles V to secure their release. As the same family alliance (João was Charles’s brother-in-law and Maria his sister) had intervened when Diogo Mendes was charged at Antwerp with secretly practising Judaism, it is likely that their financial affairs were bound up with the fortunes of these crypto-Jews. Likewise, when the Portuguese New Christian Henry Alvaros (Alvarez?) had his money and merchandise seized by two officials from Exeter because he was ‘supposed to be a Jewe’, he obtained a testimonial from Antwerp – confirmed by the Imperial ambassador – asserting that he was reputedly a Christian. This was presented at Hampton Court in January 1546.

Acts of the Privy Council, 1542-1547, p. 305

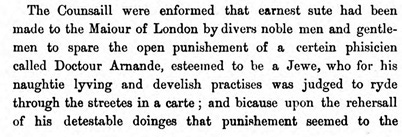

Portuguese New Christians, of course, were not the only foreigners in Henrician England. Besides the famous portrait painter Hans Holbein there was a group of musicians active at court between the 1520s and early 1540s. Drawn from Iberia and particularly northern Italian towns and cities like Bassano, Milan, Vicenza and Venice, they included viol and sackbut players. Though one scholar has ingeniously suggested that some of these musicians – notably Ambrose Lupo and the five Bassano brothers – were crypto-Jews, the evidence is questionable. Nonetheless, in 1550 we learn of Dr Arnande, a physician accused of Judaism, sentenced for his ‘naughtie lyving and develish practises’ to ride through the streets of London in a cart and then banished from the realm.

The National Archives, PC 2/4 fol. 31, calendared Acts of the Privy Council, 1550-1552, pp. 28-29

Furthermore, in 1556 a Portuguese surgeon living in Bristol was denounced for observing an important Jewish fast (Yom Kippur), while in 1575 four Portuguese New Christians resident in London were accused of deliberate sacrilege. Also noteworthy is the case of Joachim Gaunz, a Prague-born Jew and mining engineer dwelling at Blackfriars who in 1589 was apprehended following an apparent conversation with a minister in Hebrew. Gaunz was charged with blasphemously denying Jesus Christ to be the son of God and expelled.

A more successful figure was Dr Hector Nuñez, a Portuguese-born New Christian who was made a fellow of the College of Physicians and Royal College of Surgeons. From surviving correspondence – especially with Queen Elizabeth’s spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham – it is clear that Nuñez became involved in intelligence gathering, receiving letters in cipher from Iberia concealed within cargoes of wine, raisins, cochineal, figs and wax. Nuñez was also engaged in covert diplomatic activity, trying to secure an Anglo-Ottoman alliance against Spain and promoting the cause of the exiled Don Antonio to the Portuguese throne, which had been claimed by Philip II of Spain following his victory at the battle of Alcantara in 1580. Moreover, according to depositions taken before the Inquisition at Lisbon and at Madrid in 1588 – the year of the Spanish Armada, Nuñez was not acting alone but in concert with several crypto-Jews.

Based in London, where they publicly attended Lutheran churches, listened to sermons and took communion, this group was connected by marriage alliances, secretly observed Jewish rites and had ties with a clandestine synagogue in Antwerp. Among them was Benjamin George (Gonsalvo or Dunstan Añes), a freeman of the Grocers’ Company, spice trader, financial agent of the Portuguese pretender Don Antonio and father-in-law of Dr Rodrigo Lopez. An importer of aniseed and sumac, Lopez was appointed Queen Elizabeth’s chief physician about 1586. Within a year he seems to have been bribed and turned into a Spanish agent. Following Walsingham’s death in 1590 Lopez became embroiled in a power struggle between rival intelligence agencies headed by Lord Burghley – which utilized a number of crypto-Jewish merchants – and the Earl of Essex. At Essex’s instigation Lopez was arrested in January 1594 and examined about his part in an alleged plot to poison Elizabeth. A signed confession was extracted under torture and a guilty verdict obtained on the opening day of his trial. Then along with two supposed Portuguese accomplices Lopez – portrayed as ‘worse than Judas himself’ – was executed.

Rodrigo Lopez (c.1517–1594) [right, with a Spanish gentleman], by Frederik van Hulsen, 1627

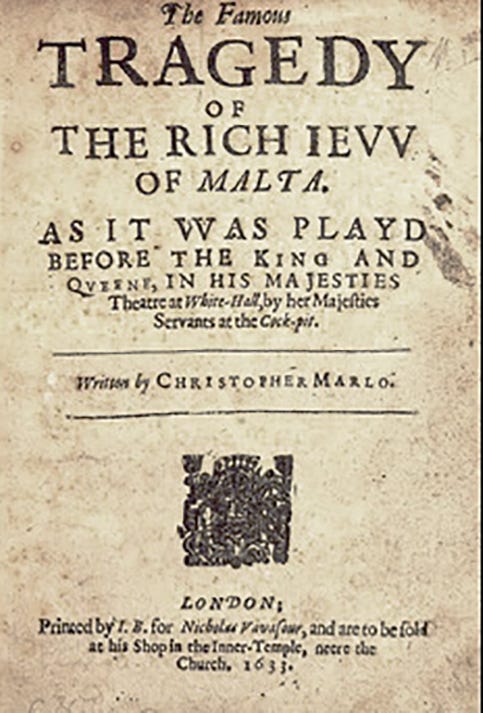

Yet the two most famous Jews of Elizabethan England appeared only on stage as villains – and neither was English. First performed in February 1592, Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta had a Machiavellian figure as its central character: Barabas. Named after the New Testament thief and murderer whom the Jews saved from crucifixion instead of Jesus (Matthew 27:16–26, Mark 15:7–15), Barabas has been regarded by one critic as representing an inversion of qualities associated with both Job and Christ. Certainly his nose and diet are mocked, while there is an allusion to his odour – a repulsive smell known as foetor judaicus which Jews were believed to emit. In addition, he is depicted as a deceitful, avaricious, Christian-hating usurer; a poisoner of wells, murderous physician and suspected crucifier of children. At the play’s conclusion Barabas suffers a terrible death, boiled in a cauldron – a traditional image of hell.

Revived to coincide with Lopez’s trial, Marlowe’s Jew of Malta together with The Jew of Venice – a lost play probably derived from Ser Giovanni Fiorentino’s Il Pecorone (Milan, 1558) – influenced William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Arguably completed after August 1596, this featured Shylock; a malicious, vengeful Christian-hating usurer who is seen as a kind of devil and likened to a dog. Critics have noted that the Jewish characters’ names are adapted or taken from Genesis 10–11 and that the word ‘Jew’ is used 58 times (variants occur an extra 14 times). Furthermore, Shylock’s famous remark ‘If you prick us, do we not bleed’ (III.i.59) has been interpreted as an allusion to the commonplace belief that Jewish males menstruated. Unlike Barabas, Shylock escapes death but only for the baptismal font.

Depiction of Shylock from William Henry Ireland, Miscellaneous papers and legal instruments under the hand and seal of William Shakespeare (London, 1796)

In the fourth and final part of this series we will move our attention from the Tudor to the early Stuart period, as well as examining developments during the English Revolution and the fate of England’s openly Jewish community immediately after the death of the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.

It is quite possible that Wm Shakespeare was sympathetic towards Jews in TMofVenice . An example is the “ if you prick us do we not bleed “ speech which could be said to demonstrate what we as people all have in common with our shared humanity. A celebration of what binds us all, rather than the “ othering “ of the Jewish community with all of the virulent antisemitism of that time.