Jews and crypto-Jews in sixteenth and seventeenth century England - part one

There are many narratives, some old, some relatively recent, covering the presence of crypto-Jews in England during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. I have tried to give an overview of that story here, which will appear in multiple parts. My account has a particular focus on developments during the English Revolution of 1641–1660, though it is also positioned within a more ambitious grand narrative recounting the Jewish, crypto-Jewish and Jewish apostate experience in England from the Norman Conquest to the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy.

I. Debating the readmission of the Jews during the Protectorate

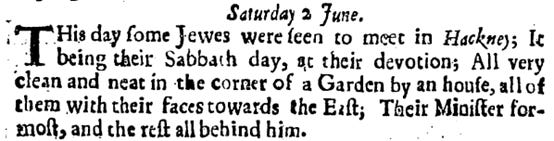

In June 1655 a newspaper reported that some Jews had been seen meeting in Hackney on a Saturday. Because it was their Sabbath they were said to be at prayer, ‘All very clean and neat in the corner of a Garden by an house, all of them with their faces towards the East; Their Minister foremost, and the rest all behind him’.

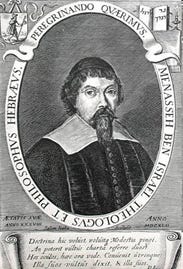

This account, however, was probably false because there were as yet no openly practising Jews in England. In fact, it was not until September 1655 that the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658) revived discussions about the readmission of Jews to England. This coincided with the arrival in London of Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel (1604–1657) who, accompanied by a Jewish merchant of Livorno named Raphael Supino, had come from Amsterdam ‘to solicit a freedom for his nation to live in England’.

Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel (1604–1657)

During his stay Menasseh lodged in the Strand ‘over against the New-Exchange’, perhaps at the house of Antonio de Oliveyra who may have been a Portuguese crypto-Jew – though this has been disputed. Menasseh was to recall that he was ‘very courteously received, and treated with much respect’. Even so, letters written by a Royalist exile in Cologne claimed that because the Jews were ‘a very crafty and worldly-wise generation’ they were unlikely to settle in England at a time of such political uncertainty. He was to be proved wrong.

Menasseh ben Israel did not come to England as a stranger for among his numerous correspondents and acquaintances were academics, scientists, politicians, soldiers and churchmen. These included such eminent figures as the Edinburgh-born preacher and advocate for church unity John Dury (1596–1680); the nonconformist minister Henry Jessey (1601–1663); the Independent minister Nathaniel Homes (1599–1678); the political theorist, reformer and proponent of religious toleration John Sadler (1615–1674); the lawyer and politician Oliver St. John (c.1598–1673); the lawyer and scholar John Selden (1584–1654); the politician Walter Strickland (1598?–1671); and the physician and reformer Benjamin Worsley (c.1618–1677). Menasseh, moreover, was a renowned scholar and soon began receiving a number of learned visitors among them Ralph Cudworth (1617–1688), professor of Hebrew at Cambridge University, Henry Oldenburg (c.1619–1677), future secretary of the Royal Society, Brian Walton (1600–1661), principal editor of Biblia Sacra Polyglotta (1653–57) and Herbert Thorndike (1597?–1672), who was responsible for the Syriac portions of the Polyglot Bible. Another person familiar with Menasseh was the chemist and physiologist Robert Boyle (1627–1691), who had visited Menasseh at his house in Amsterdam in the spring of 1648. Boyle regarded Menasseh as ‘the greatest rabbi of this age’ and on hearing of his arrival at London he went and spoke to him about Biblical Hebrew and the rites and customs of modern Jews.

On 31 October 1655 Menasseh waited outside the door as the Council of State sat in session. Menasseh hoped to present copies of his books to members of the Council and eventually a clerk went out to receive them. Among these books was probably a recently written work arguing the case for Jewish readmission to England. It was addressed to His Highness the Lord Protector of the Common-Wealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and entitled The Humble Addresses of Menasseh Ben Israel … in behalf of the Jewish Nation (1655).

Two weeks later, on 13 November Menasseh presented a petition written in French to the Council on behalf of the ‘Hebrew nation’ requesting:

1. To take us as citizens under your protection; and to defend us on all occasions

2. To allow us public synagogues in England and its dominions

3. To give us a cemetery to bury our dead

4. To allow us to trade freely in all sorts of merchandise

5. To elect a respectable person to receive our passports upon arrival and hear us swear an oath of loyalty to the Lord Protector

6. To allow our rabbis to settle internal disputes according to Mosaic Law, with right of appeal to the civil law

7. To revoke all laws against the Jewish nation, thereby enabling us to remain securely in England under the protection of the Lord Protector.

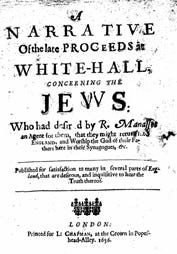

The National Archives, London, SP 18/101 fol. 237

Objections, however, were raised immediately. For example, it was feared that some Christians might convert to Judaism, while having synagogues was considered scandalous to Christian churches. Some Londoners even suggested that their trade would suffer because of Jewish competition. In the end a number of conditions were attached which included barring Jews from public office and prohibiting them from having Christian servants. In addition, Jews were not permitted to mock the Christian religion, to profane the Christian Sabbath, to prevent efforts to convert them or to print anything in English against Christianity. The last restriction was cleverly worded since it enabled Jews to continue printing Hebrew books including the Talmud, which many continental Christians – especially Catholics – found offensive. After further discussion a conference was begun at Whitehall on 4 December 1655 to discuss Menasseh’s proposals. Cromwell himself opened proceedings, which were attended by politicians, soldiers, clergymen, lawyers and merchants.

During several meetings, ‘some more private, and some more public’ an important legal point was established: although Jews had been banished from England during the reign of Edward I in 1290 there was no law – either of the land or ordained by God – forbidding their return. Consequently, Jewish immigration could be connived at so long as it was expedient. Indeed, it was said to be economically advantageous for the nation as Jewish trading networks would lower the price of imports and provide new markets for exports. Furthermore, a theologian insisted that kindness to strangers – particularly Jews – was a religious duty. But the majority of the clergy, fearful of proselytism, were against readmission. Similarly, the antisemitic pamphleteer and lawyer William Prynne (1600–1669) insisted that now was ‘a very ill time to bring in the Jews, when the people were so dangerously and generally bent to apostasy, and all sorts of novelties and errors in religion’.

William Prynne, A Short Demurrer to the Jewes Long discontinued barred Remitter into England (London: Edward Thomas, 1656)

Nonetheless, it was observed that throughout the duration of the conference, which met until 18 December 1655, Cromwell showed ‘a favourable inclination towards our harbouring the afflicted Jews’. Perhaps, like some delegates, the Protector desired the conversion of the Jews to Protestantism. A few Englishmen went further, believing that the following year would see ‘the fall of Antichrist’ which, together with ‘the Jews conversion’ would herald the destruction of the world by fire and the beginning of the 1000 year reign of Christ on earth with his Saints.

But the world did not end in 1656; not even after one sect caused thousands of pounds of damage when they deliberately burned a number of buildings in London. Instead, Jews were tacitly readmitted to England after a supposed absence of 366 years. Yet that is not to say that things were straightforward. The Whitehall Conference had ended without a definite conclusion. Moreover, according to the reports of two Italian envoys from Venice and Tuscany, the majority of English people opposed readmission. Clergymen prayed and preached against it as ‘boldly’ as they dared or else muttered ‘softly’. Even John Dury, a fervent believer in the conversion of the Jews who had initiated correspondence with Menasseh over the whereabouts of the lost ten tribes of Israel, complained that Menasseh’s demands were great. Indeed, Dury thought it was best to be wary of the Jews since they had ‘ways beyond all other men, to undermine a state’.

Similarly, Captain Francis Willoughby (1614–1666), former Royalist governor of Barbados, declared that he was opposed to religious toleration if it meant living among those who rejected Christ. There were also pernicious stories circulating, which intermingled ‘horrid’ accusations revolving around the repulsive if familiar themes of deicide, blasphemy, blood, diabolism, magic and money. Thus it was alleged that Jews celebrated Passover by feasting on matzoth mixed with the blood of murdered Christians; that Jewish seed would adulterate Christian blood; that the Jews intended to purchase St. Paul’s cathedral and convert it into a synagogue; that Jews had offered money for the Bodleian Library in Oxford, a beautiful room at Whitehall and Hebrew manuscripts in Cambridge University Library; that Jews were willing to hand over £500,000 for Brentford; that Jewish gold was being used to buy the support of wavering ministers; and that Jewish merchants were prepared to pay fantastical sums for the privilege of resettlement and endenization.

In light of this, Cromwell therefore reportedly proceeded with ‘good advice and mature deliberation’ (‘warily & by degrees’), giving his implicit permission rather than openly declaring his position. At the same time Menasseh met with Willem Nieupoort (1607–1678), the Dutch ambassador, to reassure him that he was not scheming to get extra privileges for the Jews in the Dutch Republic, only that he sought to turn Protestant England into a safe haven for those Jews fleeing from Catholic Spain and Portugal where the Inquisition operated. And then other events brought matters to a head.

On 13 March 1656 legal proceedings were begun against António Rodrigues Robles (c.1620–d.1688), a wealthy merchant of Duke’s Place, London who was accused of being a Spanish national. As England was at war with Spain at this time the goods and property of enemy Spaniards were liable for confiscation. In his defence, Robles claimed that he was actually a Portuguese-born Jew from Fundão who had fled to Spain – possibly Seville or Madrid – with his family. There the Inquisition had murdered his father and tortured and crippled his mother. Robles, who at some point was ‘cut across the face’, escaped to the Canary Islands, where he changed his name, professed to be a Catholic and worked as a custom house official in the port of Santa Cruz on Tenerife. The depositions of a number of witnesses, a few of whom were Iberian Jews, together with the questioning of Robles himself revealed that Robles, who had been living in England for four or five years, was married to a Portuguese woman of the ‘Hebrew nation and Religion’ yet had also been seen attending mass at the Spanish ambassador’s house in London until about mid-November 1655. Furthermore, Robles was at that time uncircumcised; apparently after he was circumcised his foreskin was buried in accordance with Jewish custom, but his servant dug it up as a joke – much to Robles’s displeasure.

‘The Humble Remonstrance of Antonio Rodrigues Robles of the Jewish Nation’ (25 April 1656) [The National Archives, London, SP 18/126 fol. 257]

This business forced other members of London’s secret Jewish community out into the open because many either had Spanish origins or had resided there. Accordingly, on 24 March 1656 Menasseh and six other men – Manuel Martinez Dormido (also known as David Abrabanel), Antonio Ferdinando (Abraham Israel) Carvajal, Abraham Coen Gonsales, Simon (Jacob) de Caceres, Domingo Vaez (Abraham Israel) de Brito and Isak Lopes Chillon – petitioned Cromwell for permission to practise Judaism privately in their homes; to go about unmolested; and to have a burial place outside the City of London for their dead. Cromwell referred it to the consideration of the Council of State.

The National Archives, London, SP 18/125 fol. 173

Meanwhile evidence continued to be taken in Robles’s case and by mid-May he had his ships, merchandise and other property which had been seized restored to him. Even so, the Admiralty commissioners decided he was ‘either no Jew or one that walks under loose principles, very different from others of that profession’. Then on 26 June 1656 the Council returned the Jews’ petition to Cromwell, apparently without recording the details of their discussion. This is important because a few famous historians of Anglo-Jewry such as Albert Hyamson and Cecil Roth have argued that the Council responded positively to the petition but that the crucial document was subsequently lost or destroyed. Though sceptics like H.S.Q. Henriques, Moses Gaster, and more recently David Katz were correct to dismiss this as baseless speculation, 1656 is nevertheless now widely trumpeted as an irreversible moment that marked the gradual informal readmission of Jews to England. In fact, it needs to be emphasized that there was no Act of Parliament, no proclamation from Cromwell, no order from the Council of State either welcoming Jews to England or changing their legal status as a community from aliens (foreigners whose allegiance was due to a foreign state) to denizens (foreigners admitted to residence and granted certain rights, notably to prosecute or defend themselves in law and to purchase or sell land, but still subject to the same customs duties on their goods and merchandise as aliens).

The only evidence we have suggests that publicly Cromwell remained undecided on the issue while, to quote the Tuscan envoy Francesco Salvetti, ‘conniving in the meantime at religious exercise in their private houses, as they do at present’. If the Protector gave Menasseh a verbal assurance that Jews would be permitted to continue worshipping privately in their homes then this was not the same as allowing them to build a public synagogue. It was, however, in keeping with the spirit of certain clauses of the Instrument of Government of December 1653 which had extended religious toleration to those Protestant sects that did not disturb the peace. But if the actual purpose of Menasseh’s mission was to gain official state approval for the readmission of Jews to England – rather than merely asking the authorities to turn a blind eye to their presence – then it must be judged a qualified failure.

Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Dispacci degli Ambasciatori al Senato, Inghilterra

For all these set-backs Menasseh was to suffer further still. In August 1656 the wardens of the united congregation of the Sephardic community in Amsterdam agreed to loan ‘a scroll of the Law’ to him. He appears, however, to have quarrelled with the leaders of the London community and was not chosen to lead their congregation. Instead Rabbi Moses Athias (d.1666) from Hamburg was appointed and the Torah returned. On 19 December Antonio Carvajal (c.1596–1659) signed a twenty-one year lease for a brick tenement on Creechurch Lane which by March 1657 was being converted into a synagogue. In the meantime Menasseh, alone in a ‘land of strangers’, was forced to petition Cromwell for financial assistance.

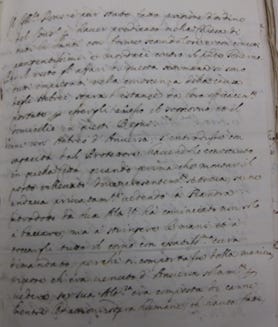

Menasseh ben Israel to Oliver Cromwell (19 February 1657) [The National Archives, London, SP 18/153 fol. 252]

He was granted a state pension of £100 per annum and at least two quarterly payments of £25 were made to him. In September 1657 his only son Samuel died. Although negotiations had begun for acquiring a burial plot at Mile End in Stepney, Menasseh decided to return to the Dutch Republic with Samuel’s body. But on reaching Middelburg, where he had relatives, Menasseh died. Samuel was buried there while Menasseh was laid to rest in the Jewish cemetery at Oudekerk near Amsterdam. In September 1658 Cromwell followed them to the grave. It was during his Protectorate that theological considerations – the necessity of converting the Jews before Christ’s reappearance – and, to a much lesser extent, economic advantages had overcome widespread hostility to tacit readmission. With his death the tiny Jewish community, which had been considered under his personal protection, was once more exposed to full-blown prejudice. Before exploring their fate during the twilight of the English republic and at the dawn of the Restoration of Charles II, however, we need to trace the long-term developments that culminated in the Resettlement.