On 6 April 1593 the Cambridge-educated religious separatists Henry Barrow (c.1550–1593) and John Greenwood (c.1560–1593) were hanged for treason at Tyburn – a notorious site of execution outside the city of London. They had been found guilty of writing and publishing seditious literature with malicious intent. Just over a month later another Cambridge-educated religious dissident, the Welsh preacher and pamphleteer John Penry (1562/63–1593), was tried twice: firstly for inciting rebellion and insurrection, and then for attacking the Church of England through the publication of scandalous writings. Penry was found guilty and on 29 May 1593 likewise hanged, this time in Surrey. As for Penry’s co-conspirator, the Warwick MP Job Throckmorton (1545–1601), he too had been put on trial in 1590. In Throckmorton’s case this was a result of the government crackdown on Protestant dissenters suspected of being involved in the writing, publication and circulation of a series of texts issued under the pseudonym ‘Martin Marprelate’ and its subsequent variants. Throckmorton, however, pleaded innocence: ‘I am not Martin, I knew not Martin’ he claimed. And because of his relatively high social status and extensive connections, not to mention legal technicalities, Throckmorton escaped the fate that would befall Barrow, Greenwood and Penry. Instead he died in relative obscurity.

Stained glass windows at Emmanuel United Reformed Church, Cambridge depicting Henry Barrow [left] and John Greenwood [right]

More than a century ago it was argued that Barrow was the main author of the Martin Marprelate tracts, although few scholars accept this now. Slightly more recently the case was made for John Penry as lead author. But this too failed to gain much support, with most specialists downgrading Penry’s role to that of minor literary collaborator or perhaps chief orchestrator of the conspiracy. Rather, both for some contemporaries and several modern experts, the evidence points to Job Throckmorton as the principal pen responsible for these writings. Another figure too must be mentioned. This was George Carleton (1529–1590), a Northamptonshire gentleman who had served as a Justice of the Peace and an MP. In 1589 Carleton married the rich widow Elizabeth Crane and it was at her house in East Molesey, Surrey near Hampton Court Palace that the first Marprelate tracts were printed. But whether Carleton merely facilitated the enterprise or whether his role extended to taking a hand in the authorship of the texts is unclear.

Turning to the choice of pseudonym, Martin was a fairly common proper name derived from the Middle English Martyn, with Martinmas or the feast of St Martin celebrated on 11 November. The prefix ‘mar’ (now obsolete), meant a hindrance or that which impaired something. A prelate was a high ranking cleric, for example an archbishop, bishop or superior of a religious house. Hence Martin Marprelate could be understood as a sort of everyman who obstructed the exercise of authority by the ecclesiastical hierarchy in Elizabethan England.

There are at least seven works associated with the name of that ‘worthy gentleman’ Martin Marprelate. Issued between October 1588 and September 1589 in print runs of between 700 and 1000 copies and priced between 6d. and 9d., these include The Epistle; The Epitome; the broadsheet Certain Mineral, and Metaphysical Schoolpoints; Hay any work for Cooper; Theses Martinianae (by ‘Martin Junior’), The Just Censure and Reproof (by ‘Martin Senior’), and The Protestation. More than one printer was involved. Initially there was Robert Waldegrave (c.1554–1603/04), a freeman of the London Stationers’ Company. He was notorious for printing material by the ‘hotter sort’ of Protestants (i.e. puritans) and had suffered imprisonment as well as the seizure and destruction of his equipment as a consequence. Using a new and distinctive continental black-letter type, Waldegrave printed the first four Marprelate pieces on a secret portable press at various locations: East Molesey, Surrey (Elizabeth Crane’s house); Fawsley House, Northamptonshire (home of a sympathiser named Sir Richard Knightley); and Whitefriars, Coventry (residence of Knightley’s nephew John Hales). Afterwards John Hodgkins and his assistants took over. They printed the remaining works at Wolston Priory, Coventry (home of another sympathiser named Roger Wigston) and Newton near Manchester. While Waldegrave fled abroad to Scotland (where he temporarily joined Penry), Hodgkins and his assistants were not so fortunate – they were captured, sent to London and tortured.

Oh read over D. John Bridges / for it is a worthy worke: or an epitome (1588)

Hay any worke for Cooper (1589)

Theses Martinianae (1589)

The Just Censure and Reproof (1589)

The Protestation (1589)

As for the wider context, the continental Reformation had begun more than seventy years previously in Wittenberg, Saxony. Among the mainstream European leaders were another Martin – Martin Luther (1483–1546), as well as Philip Melanchthon (1497–1560), Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) and Jean Calvin (1509–1564), a French theologian who had established a theocracy in Geneva. In England the Reformation started somewhat later. Although scholars do not agree exactly when, the 1530s – the decade during which Henry VIII (d.1547) declared himself head of the Church of England and then dissolved the monasteries – is widely accepted. Under Henry’s eldest surviving legitimate son Edward VI (d.1553) the process of Reformation accelerated, only for the national church to revert to Catholicism during the reign of Henry’s eldest daughter Mary I (d.1558). During the persecutions of ‘Bloody Mary’, as her enemies dubbed her, several hundred Protestants fled into exile – including a few who sought shelter in Calvin’s Geneva. Mary was succeeded by Elizabeth I (d.1603), Henry’s daughter by his marriage to Anne Boleyn.

Queen Elizabeth I

At the time the first Marprelate tract was published Elizabeth had been on the throne almost exactly thirty years. For complicated political reasons she was still unmarried, which meant that the Virgin Queen’s dynasty could not be secured. Elizabeth was eventually succeeded by her cousin James VI of Scotland – although only after she had executed James’s Catholic mother Mary, Queen of Scots in February 1587 on the charge of treason. Mary had been accused of scheming to assassinate Elizabeth in what was known as the Babington Plot, just one of a handful of attempts on Elizabeth’s life that decade. Yet a greater threat still was foreign invasion by forces loyal to Philip II of Spain, whose second marriage had been to Elizabeth’s half-sister Mary I. In July 1588 the Spanish Armada set sail for the English Channel, its prime objective to depose Elizabeth and replace her with an amenable Catholic monarch; its secondary aim to prevent English Protestants providing assistance to their co-religionists in the Netherlands who had rebelled against Spanish rule twenty years previously. Nonetheless, the Armada was defeated after which in August 1588 Elizabeth delivered a famous victory speech at West Tilbury, Essex.

English ships and the Spanish Armada

Against this backdrop the Marprelate tracts appeared. Their objective was, in a manner of speaking, to push the Church of England further away from Rome (Popery) and closer to Geneva (Calvinism). The middle way – as they saw it – that had been navigated in the form of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, with its reintroduced Book of Common Prayer (1559) and modified Thirty-Nine Articles (1571), did not go far enough. Rather, the tightly knit and well-organised network of ‘Martinists’ responsible for the tracts wanted a separation of secular from ecclesiastical power, that is distinct spheres of influence for the magistracy and ministry. Moreover, they placed great emphasis on the Bible as the word of God, a divine word which had greater authority than traditions and the pronouncements of bishops. Indeed, it was high ranking ecclesiastical officials and academics – ‘petty popes, and petty antichrists’– that the Martinists initially had in their sights. Among them was a dean of Salisbury called John Bridge, who had written an exceptionally lengthy and tedious defence of the Church of England; the Archbishop of Canterbury; the Bishops of Winchester and London; and the master of a Cambridge College. This was at a time, it must be stressed, when printed works were strictly censored by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Bishop of London and those delegated by them for that purpose. And while there was no Inquisition in the manner of Catholic Spain, there was still a Court of High Commission for investigating and punishing those found guilty of committing religious offences. Mercifully, this court could not sanction torture to extract confessions nor could it impose the death penalty. It did, however, operate in tandem with the secular Court of Star Chamber, whose officials investigated and heavily fined some of those suspected of being involved in the Marprelate affair.

Not all the Martinists’ accusations were accurate, or even coherent. Nonetheless, they succeeded in breaking the mould of how religious disputes should be conducted. Indeed, a striking feature of the tracts was that they were written in English rather than Latin so that they could reach as wide an audience as possible; even those unable to read might still hear the words spoken aloud. The prose was colloquial and playful, relying on spontaneity, irony, parody and alliteration: ‘proud, popish, presumptuous, profane, paltry, pestilent and pernicious prelates’ gives a flavour. Most likely the author(s) were influenced by the extemporisation of actors on the Elizabethan stage as well as jest books and ballads. As for the satire, it was comparatively savage. Indeed, it did not follow accepted norms which derived from Roman models. Rather, Marprelate mixed sometimes well-informed anecdotes with sexual insults and subversive rhetoric.

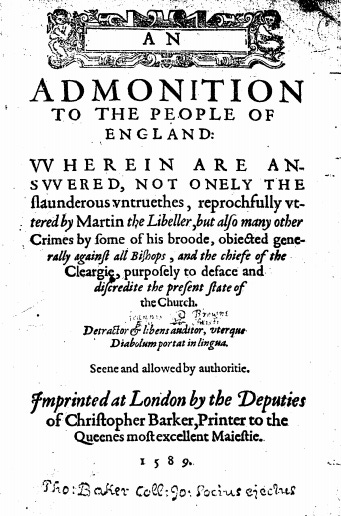

The official response was outrage. Scandalised, the Bishop of Winchester declaimed in An Admonition to the People of England (1589) against these ‘odious libels’ crammed with ‘untruths, slanders, reproaches, railings, revilings, scoffings and other intemperate speeches’ that never before had been seen committed to print. Further propaganda intended to maintain the status quo appeared, including a royal proclamation and a sermon. Yet the most remarkable aspect of the officially sponsored counter-narrative was how the ecclesiastical authorities, with full governmental support, managed to swiftly adopt the Martinists’ innovative polemical strategies and turn those weapons against the very people who had developed them. To accomplish this they hired skilled writers, most likely including the prolific Thomas Nashe (1567–c.1601) and the playwright John Lyly (1554–1606). Altogether more than twenty anti-Martinist works were published with titles like Pappe with a hatchet (1589), An Almond for a Parrot (1589), and Martins Months mind (1589). Even so, in an unanticipated irony, at least one of these anti-Martinist pamphleteers became so infected with the Martinist strain that he began writing some pieces in a Martinist vein.

An Admonition to the People of England (1589)

An Almond for a Parrat, Or Cutbert Curry-knaves Almes (1589)

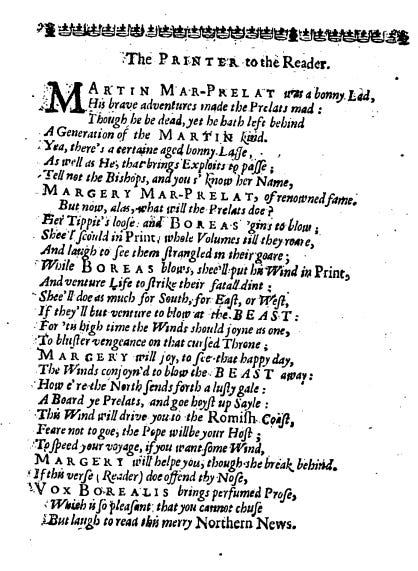

In the short term, as we have seen, the Martinists were defeated. Not only that, but their more cautious and moderate puritan brethren – many of whom had been quick to distance themselves from the Martinist project – were damned by association. A further blow was struck in July 1591 with the execution of William Hacket, a self-proclaimed prophet from Northamptonshire. Hacket and his accomplices planned to abolish church government by bishops and depose Queen Elizabeth. Their widely publicised fate, however, served only to bring the puritan movement into further disrepute. But in the long term, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, Martin Marprelate re-emerged together with a fictional offspring. In 1637 his spectre was invoked by seditious parishioners in Northamptonshire refusing to pay tithes and ship money. Then, with England on the brink of Civil War between Royalists and Parliamentarians, a pamphlet entitled Vox Borealis (1641) printed by ‘Margery Mar-Prelat’ appeared. Here the printer directly addressed the reader in verse:

Martin Mar-Prelate was a bonny Lad,

His adventures made the Prelates mad:

Though he be dead, yet he hath left behind

A Generation of the MARTIN kind.

Vox Borealis or The Northern Discoverie (1641)

The following year Marprelate’s Hay any work for Cooper was reprinted by ‘Martin the Metropolitan’. Thereafter a number of similar titles were issued, notably a satirical plea for religious toleration by ‘Young Martin Mar-Priest, son to old Martin the Metropolitan’.

Many of these works were by the future Leveller leader Richard Overton. Appropriating and refashioning the identity of a famous if pseudonymous Elizabethan antagonist of ecclesiastical authority, Overton’s purpose was to fire shots with paper bullets against persecution and tyranny in the pamphlet wars of the English Revolution. Leaders die. Their followers die. But ideas can and do endure – as do the innovative ways in which they can be expressed and spread.

An excellent piece that analyses in a few paragraphs the intricacies of censorship, religious dissent and power struggle in Elizabethan England.