Q. Are the Apocrypha Books to be owned as Gods Word?

A. No. Every word of God is pure: add thou not unto his words, least he reprove thee, and thou be found a lyar (Proverbs 30:5–6).

[Anonymous, A Protestant catechisme for Little Children, or Plain Scripture against Popery (1673), pp. 3–4]

Protestantism is a religion based on an anthology: the Bible. English Protestants, however, generally accepted fewer holy books than Catholics. Scripture alone, rather than the Papacy or Church councils, was paramount. Yet which scriptures were to be accepted and which rejected was no straightforward matter. This four-part post begins with a brief account of how and why certain Jewish writings came to be regarded as apocryphal, highlighting the crucial contribution Jerome’s contentious canonical theory would play. It also underscores the fact that the Apocrypha was a Protestant construction, one moreover that reflected the privileging of Jewish texts available in Hebrew over those then extant in Greek. For the gradual evolution of the Apocrypha as a distinct corpus was partially a by-product of the Humanist return to the sources – specifically Hebrew.

Previous studies of the Apocrypha in early modern England have tended to stress two points: firstly, that the removal of these books from the Old Testament was unauthorised, lacking explicit royal and ecclesiastical sanction; secondly, that their influence was greater than commonly recognised. Both approaches date from the turn of the twentieth century. While the former may have been motivated by a desire to foster closer ties between Anglicans and Catholics, the latter was intended to rescue these writings from oblivion. Here I want to suggest that in addition the Apocrypha was important because of its inherent potential to exacerbate religious conflict – not just between Catholics, Lutherans and Calvinists, but also between moderate churchmen and puritans. Thus, to take an emotive example, the controversial Hebraist Hugh Broughton urged printers to omit the Apocrypha from the bible, dismissing these ‘unperfect histories’ as nothing better than trifling Jewish fables and ‘mean wits’ work:

A Turkey leprous slave might as seemly be placed in seat, cheek by cheek, betwixt two the best Christian Kings; as the wicked Apocrypha betwixt both testaments. And no monster of many legs, arms, or heads can be more ugly.

Hugh Broughton (1549–1612)

I. Historical background and definitions

Apocrypha is a Latin neuter plural noun (singular: apocryphon). It has a Greek etymology, derived from an adjective meaning hidden away, kept secret. The word occurs several times in the Septuagint (Deuteronomy 27:15, Isaiah 4:6, Psalms 17:12, 27:5), a Greek version of the Hebrew Scriptures originally written on papyrus or leather scrolls and compiled, according to the legendary Letter of Aristeas, in the third century B.C.E. by seventy – or seventy-two – translators for the benefit of Alexandrian Jews.

Initially the Greek adjective, when applied to books, was occasionally used in an approving manner to describe writings containing mysterious wisdom too profound or holy to be communicated to any save the initiated (cf. Daniel 12:4, 2 Esdras 14:45–46, 1 Enoch 108:1). The Greek-speaking Origen (c.185–c.254), however, subsequently employed the term to distinguish between writings read in public worship and those of questionable value which were studied privately. Yet Origen also used the word negatively to describe something false, while his contemporary Clement of Alexandria (c.150–c.210 x 215) employed it with reference to dubious secret works possessed by heretics – especially Gnostics. This last, pejorative sense eventually became prevalent among Latin speakers. Accordingly, when from the mid-fourth century the Church began the process of establishing a uniform canon by drawing up authoritative lists of books regarded as sacred scripture (essentially the Septuagint for what since the late second century had gradually become known as the ‘Old Testament’), the adjective was applied to texts deemed heretical or spurious. Thus Augustine of Hippo (354–430) declared in The City of God:

Let us omit, then, the fables of those scriptures which are called apocryphal, because their obscure origin was unknown to the fathers from whom the authority of the true Scriptures has been transmitted to us by a most certain and well-ascertained succession. For though there is some truth in these apocryphal writings, yet they contain so many false statements, that they have no canonical authority.

It should be stressed that here Augustine was condemning writings deceitfully written under the name of the antediluvian patriarch Enoch as well as other counterfeit compositions attributed to various prophets and apostles. By contrast Jerome (c.331 x 347–420) was the first to designate a particular corpus of writings as apocryphal because of their exclusion from what had by then become a closed Jewish canon. These were Jewish compositions omitted from the Hebrew Bible but with the exception of 2 Esdras nonetheless found in certain versions of the Septuagint preserved in codices, and hence generally included in the canon being defined by the Church.

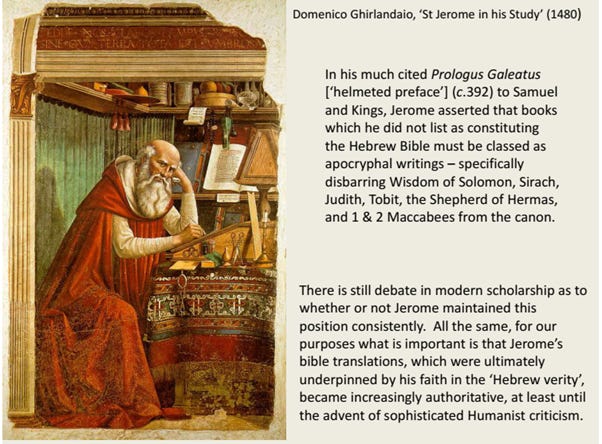

In 382 and with the likely approval of Pope Damasus (d.384), Jerome undertook a new Latin version of the Scriptures to supersede variants of what we now call an Old Latin version based on the Greek. Progressing over a period of more than twenty-five years from Greek to Hebrew sources and in the process moving from Rome to Bethlehem, Jerome asserted in his much cited Prologus Galeatus [‘helmeted preface’] (c.392) to Samuel and Kings that books which he did not list as constituting the Hebrew Bible must be classed as apocryphal writings – specifically disbarring Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Judith, Tobit, the Shepherd of Hermas, and 1 & 2 Maccabees from the canon. There is still debate in modern scholarship as to whether or not Jerome maintained this position consistently. Elsewhere, for example, his pronouncements accorded with contemporary usage; ‘beware of all apocrypha’ he advised, ‘they were not written by those to whom they are ascribed … many vile things have been mixed in … they require great prudence to find the gold in the filth’. All the same, for our purposes what is important is that Jerome’s bible translations, which were ultimately underpinned by his faith in the ‘Hebrew verity’, became increasingly authoritative, at least until the advent of sophisticated Humanist criticism. So much so, that from the 1520s they were being referred to as the vulgata editio, or as the English exile translators of the Douay Old Testament (1609–10) first called them, the vulgate Latin edition. Moreover, his unheeded call for the Church to reject the Septuagint in favour of the Hebrew Bible as the basis of the Old Testament, together with his criteria for determining which books should be considered apocryphal, would provide vital ammunition in the polemical battles waged between Protestant reformers and their Catholic adversaries.

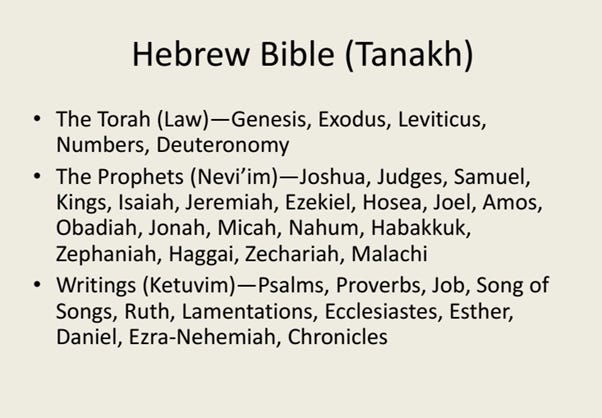

Following the Romano-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (c.37–100), Origen’s preface to his Commentary on the Psalms and Athanasius of Alexandria (d.373), Jerome held that the twenty-two books in the Hebrew Bible corresponded to the number of letters in the Hebrew alphabet (the twelve minor prophets counting as one book). Although, as Jerome acknowledged, some reckoned there were twenty-four books (corresponding to the twenty-four elders of Revelation 4:4), this discrepancy mattered less than the tripartite division of the Hebrew Bible that he adopted; namely the Pentateuch, Prophets, and Hagiographa (five, eight and nine books respectively). Here too Jewish precedent was crucial, for the dominant strain of rabbinic second Temple Judaism divided its Bible into three sections: the Laws (Torah), Prophets (Nevi’im), and Writings (Ketuvim).

Furthermore, whereas Athanasius in his 39th Festal epistle (367) had distinguished three types of writings – that is canonical (twenty-two Old Testament and twenty-seven New Testament books), non-canonical (suitable to be read by new converts ‘for instruction in the word of godliness’, including Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach, Esther, Judith and Tobit), and the apocrypha (which were the ‘invention of heretics’) – Jerome designated the non-canonical books apocryphal while likewise recognising their didactic rather than doctrinal value:

The Church reads [these] books ... for the edification of the common people, but not as authority to confirm any of the Church’s doctrines.

This again significantly contributed towards establishing the boundaries of what became highly contested theological territory during the Reformation and its aftermath.

Here my definition of the Apocrypha reflects early modern English Protestant usage. They are taken to be the books designated as such in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English printed bibles. Adhering to the sixth of the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England (1571), the King James Bible (1611) named and ordered fourteen books, giving the number of chapters in each; 1 Esdras (9), 2 Esdras (16), Tobit (14), Judith (16), the rest of Esther (6), the Wisdom of Solomon (19), the Wisdom of Jesus the son of Sirach, or Ecclesiasticus (51), Baruch, with the epistle of Jeremiah (6), the Song of the Three Holy Children (1), the History of Susanna (1), Bel and the Dragon (1), the Prayer of Manasses king of Judah (1), 1 Maccabees (16), and 2 Maccabees (15). Previously 3 Maccabees had also been included in Edmund Becke’s 1549 Bible, while 4 Maccabees and Psalm 151 were consistently omitted despite having been preserved in some Septuagint manuscripts.

The texts under discussion were written during what scholars now call the late Second Temple or intertestamental period; that is between approximately 200 B.C.E. and 100 C.E. Intended primarily for a Jewish readership the original language of composition was probably mainly either Hebrew or Aramaic, with the exceptions of Wisdom of Solomon, 2 & 4 Maccabees and possibly also the History of Susanna and the Prayer of Manasses, which appear to have been written in Greek. Where they originated is more problematic. All are anonymous or pseudonymous with the exception of Sirach, which we know was translated from Hebrew into Greek by the author’s grandson after he went to Egypt in 132 B.C.E. (the original can most likely be situated within a Jerusalemite milieu from 196–170 B.C.E.) The other Hebrew or Aramaic writings, to quote Martin Goodman, ‘may have been written either in the Land of Israel or in Babylon or Syria or even in Egypt’, while ‘those written in or translated into Greek may originate from any part of the Eastern Mediterranean world, including quite possibly Judea’. Consequently the historical context of each book varies, but they span from when Alexander the Great’s Macedonian successors were still dominant (the Ptolemies in Egypt, the Seleucids in Babylonia and northern Syria) to the Flavian dynasty of Roman emperors. Within this broader framework various branches of Judaism came into prolonged contact with Hellenistic and then Roman culture. Although assimilation was widespread there were instances of violent resistance, notably the Hasmonean revolt recorded in 1 & 2 Maccabees. As Goodman observes, Jews wrote extensively during this period, often embracing Hellenistic literary forms. The Apocrypha therefore represents just a very tiny fraction of their activities and why this anthology – or at least its core – was selected for inclusion within the Septuagint and other texts passed over is a good question for which the most convincing explanation is chance. Individual writings had been preserved on one or more scrolls, which were kept together in the same box. But when the assorted contents of these boxes were transcribed onto codices distinctions as to each book’s status were lost. Hence they are a miscellany, embracing a range of genres: sapiential, moralising, devotional and epistolary literature intermingled with philosophy, purported history and apocalyptic.

Among Jews the prevailing attitude was that these writings were not divinely inspired because they were set down after prophecy was believed to have ceased in Israel (cf. 1 Maccabees 4:46, 9:27, 14:41). Thus these ‘outside books’ were withdrawn from use and not included in what became ‘Holy Writ’, that is the Hebrew Bible. A tractate of the Mishnah (compiled late 2nd century C.E.) even attributed to Rabbi Akiva the saying that an Israelite man who ‘reads the external books’ shall have no share in the world to come. What these ‘external books’ were remains a puzzle for modern scholarship. But Sirach, despite being a relatively recent work by a known author, continued to be cited regularly in Talmudic and other rabbinical literature – perhaps because Akiva’s dictum meant it was to be read privately rather than expounded publicly in the synagogue as scripture. Significantly, the Apocrypha are not quoted directly in the New Testament, though possible allusions have been detected (Matthew 27:43; Luke 10:8; John 6:35; Romans 1:20–29, 9:20–23, 12:15; 1 Corinthians 6:12, 10:23; 2 Corinthians 5:1, 5:4; Ephesians 6:13–17; Hebrews 1:3, 11:35–37; James 1:12, 1:13, 1:19, 3:6, 5:3). As we have seen, early Christian writers who knew the Septuagint or one of its Old Latin versions were familiar with the Apocrypha, tending initially to regard them as Scripture before sometimes relegating them, as least in Western and North African Christianity, to an intermediate or – to use a term favoured by Rufinus of Aquileia (d.410) – ‘ecclesiastical’ category.

Just as our modern sense of the Apocrypha is based on an evolved Protestant construction, so this corpus must also be distinguished from another Protestant category: pseudepigrapha. Meaning falsely ascribed and used in English since the 1620s as a description of spuriously attributed books, this problematic term gained greater currency in biblical scholarship with the publication of the German Lutheran bibliophile Johann Albert Fabricius’s Codex pseudepigraphus Veteris Testamenti (Hamburg and Leipzig, 1713). Among this hodgepodge were Greek fragments of 1 Enoch, the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, the Letter of Baruch and 2 Esdras. Yet unsurprisingly, subsequent attempts to rationalise criteria for inclusion in this category failed. For beyond the fact that these were believed to be the residue of pre-Christian Jewish texts of indeterminate authorship omitted from the Septuagint and which were not rabbinic, they shared little in common. Indeed, several books in the Hebrew Bible and Apocrypha are evidently pseudepigraphical: Samuel, Daniel, Ecclesiastes, Proverbs and Wisdom of Solomon to name but some. Moreover, because literary impersonation (not always undertaken with intent to deceive), putting rhetorical speeches into the mouths of historical figures and plagiarism were widespread in antiquity, we should not impose our relatively recent sense of authorial identity and intellectual copyright. Motivation may have been provided by seeking greater authority for a text, financial gain, entertainment, adulation or, conversely, mischievousness. It is therefore preferable to use comparatively neutral terms like uncanonical or extra-canonical, and an account of the reception of these writings in early modern England together with those excluded from the New Testament deserves a separate study.

In part two of this post, our focus will turn to the Reformation and in particular Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt, Martin Luther and the first printed English Bibles issued during the reign of Henry VIII.

I am very grateful to Jeremiah Coogan for pointing out a couple of corrections and some suggested amendments to the original version of this post. I've incorporated Jeremiah's points in a revised version but remain, of course, entirely responsible for any remaining errors or shortcomings.