In the second part of this essay we saw how there was much more to say about Edward Thompson’s recovery of the Muggletonian archive than is commonly supposed. Indeed, through his energy and commitment Thompson played a crucial role in securing the archive for posterity. This was achieved through the British Library’s purchase of the Muggletonian manuscripts together with examples of the more important printed texts on 23 January 1978. Usually the story ends here. But that was not the end of the matter since there is still the fate of the Muggletonian material declined by the British Library to consider. As far as I am aware, what happened next is discussed here for the first time. Moreover, I would like to take this opportunity to thank everyone who patiently and generously responded to my requests for information. Without the benefit of their recollections (which did not always agree on specific details), nor the selected documents I was kindly provided with, it would not have been possible to write this account.[1]

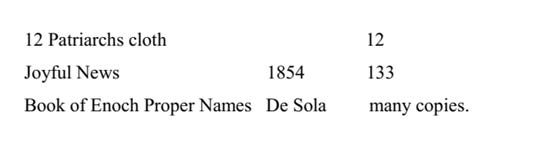

To recap: previously we noted that Edward Thompson knew of a preliminary book list in March 1975 that had presumably been drawn up by Philip Noakes. Another undated list survives in the handwriting of Jean Noakes. It is arranged by apple box number, running consecutively from no. 1 to no. 85 but with nothing itemised for three boxes (nos. 62, 80, 81), which may have contained manuscripts. The printed titles held within each box were recorded together with the approximate number of copies of each title – except for a few instances where it just says ‘many copies’. For example, the entry for box 70 reads:

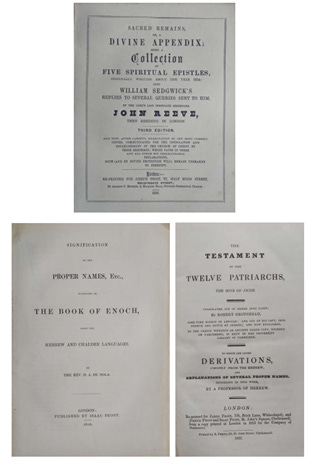

Altogether there were substantially more than 6,450 separate printed items, perhaps in excess of 7,000. Regarding the works themselves, these consisted of numerous copies of eighteenth- and nineteenth century reprints of writings by Reeve and Muggleton; multiple copies of Muggletonian writings by John Saddington and Thomas Tomkinson; and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century editions of other Muggletonian texts.

By January 1978 when the British Library purchased the Muggletonian manuscripts, these ‘surplus books’ were being stored at Martin and Gail Johnson’s new home where they occupied an entire room. This was in the Mendip Hills at the village of Stoney Stratton, Somerset. As mentioned in part two, a few months before the manuscript sale Mr Johnson had already been in touch with the antiquarian bookseller Anthony Garnett (who was based in St Louis, Missouri). Garnett had been confident that it would be ‘relatively easy’ to find buyers for these Muggletonian books. Yet as we shall see, it would prove to be anything but a straightforward undertaking.

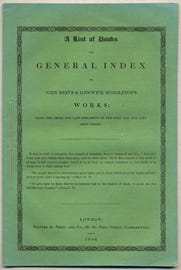

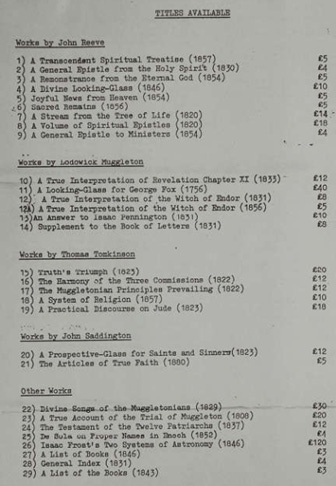

In Garnett’s view ‘the best way of disposing of the material in quantity’ was to make ‘individual approaches to libraries’ and sell them ‘a collection (i.e. one of everything)’. Accordingly, he recalls acquiring a ‘stockpile’ containing ‘a great many’ duplicate copies of a ‘relatively small number’ of titles from which he was able to put together ‘several small collections’. By late August 1978 Garnett had almost completed a catalogue of what he would call ‘A Muggletonian Collection: The books of a 17th century religious sect’. This catalogue lists 41 separate items together with their price, ranging from $10 for A List of Books and General Index to John Reeve & Lodowick Muggleton’s Works (1843) to $70 for Isaac Frost’s Two Systems of Astronomy (1846). The cost for a whole collection would be $950.

Garnett, moreover, was encouraged by the relatively ‘enthusiastic responses’ he had received and thought that one of the ‘the biggest selling points’ would be that ‘in almost all cases’ major institutional libraries did not possess copies of these works. By mid-January 1979 twenty copies of each of the books were ‘packed up and ready to be shipped’ to Garnett’s antiquarian bookshop in St Louis. Garnett’s agreed commission on the sale of the Muggletonian material would be ‘25% of the selling price’, while he would incur all expenses involved including transportation and cataloguing.

There was some success at the start: the ‘first and most complete selection’ was purchased by the University of South Carolina Library. This collection included several annotated copies of Divine Songs of the Muggletonians (1829) and some titles inscribed with the owner’s signature, among them a copy of John Reeve’s Sacred Remains (1751?) signed Mr and Mrs F.E. Noakes. A second collection was bought by Princeton University Library which ‘acquired more than 30 separately published Muggletonian tracts’. Unfortunately, as Garnett informed Mr Johnson in January 1981, the two libraries to which he had managed to sell collections of the Muggletonian material ‘both seemed to find excellent reasons for not paying for them’; or rather they did pay, but it took much longer than expected. Besides these two libraries, however, there had been ‘virtually no action’.[2] Nor had a single British university responded to Garnett’s publicity notices on the Muggletonians. In short, ‘as a year, 1980 should not have been allowed … it was basically a long series of disasters from beginning to end’. A little over nine months later, not having heard from Garnett for a considerable time, Mr Johnson wrote to him requesting that he return the Muggletonian books still in his possession since he intended ‘to dispose of the remainder as a job lot’. The family were grateful to Garnett for his efforts even if understandably ‘disappointed with the total sales’. Moreover, with Mrs Noakes intending to retire the following year, she was ‘anxious to settle the business as soon as possible’.

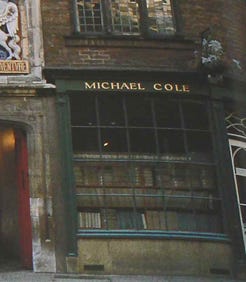

On 19 September 1981 Michael Cole, an antiquarian bookseller based in York, responded to a letter he had received from Mrs Noakes doubtless concerning the sale of what remained of the Muggletonian collection. Cole mentioned that he had ‘purchased the previous collection in a major London auction house’ but had been struck by the lack of interest shown, which was ‘of very large proportions’. He was also concerned that the Muggletonian books were being stored in apple boxes since it might make ‘thorough inspection somewhat difficult’. Presumably it was about this time that Cole recalled having received a telephone call from Mrs Noakes who informed him that she had ‘a few thousand early-mid 19th century copies’ of Muggletonian writings. Mrs Noakes wanted to know if he was willing to purchase the entire collection. From previous experience Cole reckoned that there were twenty-seven different printed Muggletonian titles. He therefore gently suggested to Mrs Noakes that she must be mistaken in her assessment of ‘a few thousand’ only to be patiently corrected when she replied ‘yes, but I have several hundred copies of each’.

Cole’s understanding of the situation, gleaned partly from conversations with Mrs Noakes, was that Thompson had advised her ‘to dispose of the printed volumes as being of little interest’ – an opinion doubtless shared by representatives of the British Library. In short, given that the remaining archive was of comparatively less ‘interest and value’, his main role was ‘to take the books off Mrs Noakes’s hands’ since previous visitors had already told her their ‘likely worth on the market’. That is partly borne out by Mr Johnson’s memory that ‘after consulting with academics’ they disposed of the material to Garnett and Cole – although the family retained ‘a sample set of material’ for each of Mr Noakes’s four grandchildren (Gail’s two sons and Carole’s two daughters).

By the beginning of November 1982 Mrs Noakes had remarried. The books were now her daughter Gail’s responsibility. However, Gail’s husband (Mr Johnson) had a new job which necessitated selling their house in Somerset. As a consequence, with nowhere to store the Muggletonian books she was ‘anxious to dispose of [them] as quickly as possible’. She therefore wrote to Garnett imploring him to sell his remaining Muggletonian stock (‘a suitcase full of books’). A few days later Cole wrote to Gail indicating that he and his business partner John Morris were ‘interested in purchasing the complete stock as a long-term investment’. Over the past year their enquiries made world-wide had indicated that although there was presently insufficient demand ‘to take up more than a very small proportion of the large numbers of each title available’ more customers should emerge over a period of time.

Cole then travelled to a rural setting in a transit van. According to his correspondence he intended to go to Somerset in November 1982 and then to Kent at the beginning of January 1983. Cole maintains that he visited Mrs Noakes’s property in Kent. At any rate, regardless of the location, he recalled being taken to a barn (it is unlikely to have been the family farm since the Noakes had vacated it in 1972). There he viewed the residue of the archive stored in what he thought were ‘the original wooden crates from the 19th century printers’. Whether or not these were the original orchard boxes that Mr Noakes had used to ‘rescue the books from the bombed meeting house’ they were certainly part of the Muggletonian collection. More importantly, according to Cole’s recollection Mrs Noakes and her daughter Gail were pleased to find someone willing to take the volumes off their hands and agreed a price with him.

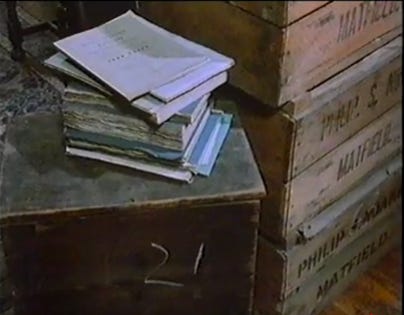

Three of the original boxes used to store Muggletonian printed works; those shown here were cleaned up and wax-polished [photograph by Michael Cole]

On examining the collection with his business partner, Cole recalled finding that they owned between ten and twenty complete sets of the published writings (consisting primarily of early nineteenth-century reprints) as well as some thirty or forty almost complete sets. These generally lacked Nathaniel Powell’s eyewitness A true account of the trial and sufferings of Lodowick Muggleton (1808). For commercial reasons Cole reprinted this pamphlet in facsimile (York, 1983) to fill gaps in otherwise complete sets. There remained perhaps ‘another 100 or 200 copies’ of titles individually saleable on the antiquarian book market.

Muggletonian works sold by Michael Cole

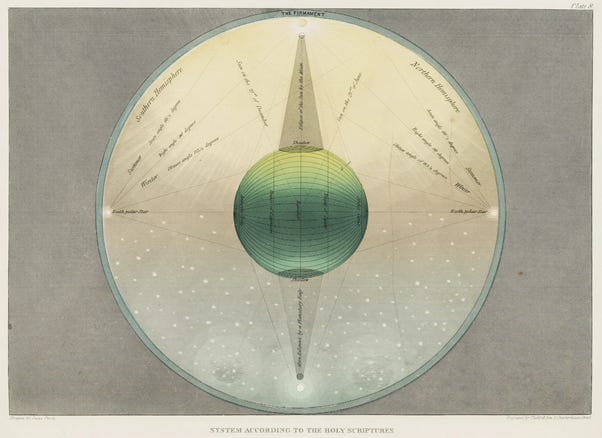

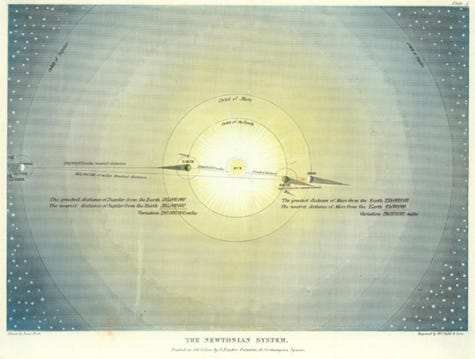

Yet the most valuable items were approximately twenty copies of Isaac Frost’s Two Systems of Astronomy (1846), which includes eleven large oil coloured prints by George Baxter made from engravings based on Frost’s drawings. Sets of six of these coloured prints measuring 28 x 21 cm appear to have circulated privately among Muggletonians and within the past twenty-five years have tended to be auctioned at prices ranging from £1,500 to £2,500.

Isaac Frost, Two Systems of Astronomy (London: George Baxter, 1846)

Isaac Frost, Two Systems of Astronomy (London: George Baxter, 1846)

In the meantime, word had spread among historians as to the existence of the Muggletonian archive. Thus in October 1978 John F.C. Harrison (1921–2018) of the University of Sussex, who had recently discussed eighteenth-century Muggletonianism in his forthcoming book The Second Coming: Popular Millenarianism, 1780–1850 (1979), wrote to Mr Johnson enquiring about the possibility of purchasing some Muggletonian books. Harrison’s colleague at Sussex William Lamont (1934–2018) likewise became excited at the prospect of ‘reassessing the movement in the light of these discoveries’. Indeed, Lamont was only the third scholar to consult the unbound manuscript material in the British Library. Christopher Hill too was interested, ‘pestering’ Gail Johnson for a copy – bound or in loose sheets – of a three volume 1831 complete edition of Reeve’s and Muggleton’s works. He was eventually supplied with these writings in mid-September 1981 at the cost of £125 with an apology that ‘the Muggletonians complicated things by mixing up titles in different volumes’. Afterwards, Lamont, Hill and Barry Reay co-wrote The World of the Muggletonians (1983), its title in homage of A.L. Morton’s The World of the Ranters.

The World of the Muggletonians was published on 10 February 1983 by Maurice Temple Smith, the same firm that had issued the first hardback edition of Hill’s The World Turned Upside Down in 1972. According to their press release, they were participating in a ‘unique collaboration’ with Cole who ‘by an extraordinary coincidence’ used the opportunity to publicise his recently acquired ‘hoard of Muggletonian books – some thirty different titles in multiples aggregating about 6,000 volumes’. Temple Smith and Cole believed this to be:

the first occasion on which the publication of a book of major importance in an academic field has been accompanied by a catalogue containing multiple copies of original antiquarian books on the same subject.

The extraordinary recovery of the Muggletonian archive was also considered suitably dramatic for television. So between 28 February and 4 March 1983 the BBC set about filming several segments for an episode of Timewatch. These included one in Matfield, Kent with Mrs Jean Barsley (Mr Noakes’s widow) and Willie Lamont; one at Michael Cole’s antiquarian bookshop on 41 Fossgate, York; and one with Christopher Hill at his home in Sibford Ferris, Oxfordshire. The director was Diana Lashmore and the reporter Simon Winchester, who would write the bestselling The Surgeon of Crowthorne. Later that same month the programme was broadcast with about eighteen minutes of footage. It featured a ‘deathless exchange’ between Mrs Barsley and Lamont, as well as shots of Muggletonian books and pamphlets in their original boxes at Cole’s shop.

Willie Lamont and Mrs Jean Barsley in discussion

Muggletonian books and pamphlets shown on top of a box numbered 21 at Michael Cole’s antiquarian bookshop in York. On the right are three of the original apple boxes with the name Philip Noakes of Matfield clearly displayed.[3]

Christopher Hill on Timewatch (March 1983)

Willie Lamont on Timewatch (March 1983)

The only items from the Muggletonian archive still in Cole’s possession in 2005, however, were a few sets of Baxter’s coloured prints. Over a period of about two years he had sold the full and partly complete sets of published writings to a number of university libraries, including Stanford and Yale, not to mention the John J. Burns Library, Boston College as well as private collectors such as the Blake scholar G.E. Bentley (now held at the E.J. Pratt Library, University of Toronto).[4] The bulk of the remaining archive consisted of ‘between 1000 and 2000 copies each’ of about four ‘minor’ titles. Since these volumes had ‘absolutely no market value whatsoever’ they were for the most part ‘selectively pulped’. The final remnants of the collection – twenty-two items – were sold by Cole to Gage Postal Books of Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex in the mid-1980s. Fortunately, I was able to purchase fourteen of these works in 2005.

Some Muggletonian titles I acquired from Gage Postal Books in 2005

[1] I am most grateful to Michael Cole, Anthony Garnett, Emmeline Garnett, Martin Johnson, William Johnson, Kevin Lewis, Carole Noakes, Kevin Repp and Simon Routh for their generous help in answering my research enquiries.

[2] In 1979, however, Duke University had acquired The Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs (1837) from Garnett.

[3] This was apparently normal practice since these boxes were taken to Covent Garden and later returned to the farmer for re-use.

[4] Bentley’s purchase cost $322.50 (Canadian $).

Very well done, Ariel! Concise, clear, and right to the point. These short essays are very helpful, particularly to an educated lay audience.

PULPED?!