The Muggletonians, 1652–1979? Part two

The story of historian Edward Thompson’s recovery of the Muggletonian archive is relatively well-known and has been told before.[1] Yet as we shall see, not only is there much more to add but in several places also aspects that must be modified.[2]

Following the publication of an article by Christopher Hill (1912–2003) on ‘Milton the radical’ in the Times Literary Supplement (29 November 1974) a correspondence about Muggletonian doctrine ensued, enabling Thompson to publicise his research and ask readers for information. According to Thompson, within days a friend informed him that she had been contacted by Mr Martin Johnson, a further education lecturer and a son-in-law of the so-called ‘last Muggletonian’ – Mr Philip Noakes (c.1905–1979). Mr Johnson, however, is certain that it was his friend and colleague Emmeline Garnett who drew his attention to Thompson’s letter in the Times Literary Supplement (7 March 1975) – apparently at a cocktail party.[3] After speaking to his father-in-law, Mr Johnson rang Thompson informing him that Mr Noakes was the custodian of the Muggletonian archive and that the sect’s books and papers had been stored in a cellar in Tunbridge Wells ‘for safekeeping during the war’. Thompson was apparently ‘incoherent with excitement and couldn’t wait to meet Mr Noakes’. Of this more will be said shortly. But beforehand a few words about Philip Noakes, Muggletonian fruit farmer of Matfield, Kent and his family.

Philip Noakes

Philip Noakes was one of four children born to Frederick and Florence Noakes, but the only one to embrace his parents’ Muggletonian faith. ‘In common with all Muggletonians’ he did not attend church except when required – and then only for social functions like weddings and funerals. Indeed, Fred and Flo Noakes used to go to local gathering places after church services because ‘mixing with other townspeople’ was deemed ‘good for business’. Moreover, in keeping with Muggletonian practice Mr Noakes appears not to have discussed his faith with family members (non-believers ignorant of the Muggletonian Commission could still be saved, but not if they were exposed to and rejected it). To quote from a letter written by his father Fred Noakes to a fellow believer in 1934:

Christ called the Apostles, not persuaded them to follow him, because he knew the seed of faith was in them, but we don’t know what is in our fellow creatures and are in danger of throwing pearls to swine and increasing their punishment if they deride it. But should a manifestly ‘lost sheep’ come our way, one who genuinely cannot find rest for his soul in any orthodox religion, then we are quite right not to hide our light under a bushel, but carefully feed him with milk and then judge if he can stand strong meat.

Fred Noakes had previously been in contact with an editor at the Daily Express regarding some necessary corrections to a piece on the Muggletonians. He wrote on 15 March 1926:

The writer was evidently very badly informed of his subject for Lodowick Muggleton never claimed to be the Messiah … the Books written by [Muggleton] and his partner John Reeve … contain the purest and most complete spiritual revelation that the world has ever seen, or ever will see, and although it is getting on for 300 years since they were written they will never be completely lost as long as this earth exists. That Reeve and Muggleton were divinely inspired their followers to this day have no doubt whatever.

All the same, as he confided to a correspondent some five years later, Fred was worried about how few believers remained:

We are a small and slowly diminishing community, but that does not dismay us as we firmly believe the principles as set forth by Reeve and Muggleton will endure as long as the world lasts.

He shared the same concern with another correspondent in November 1934:

Our ‘Little Flock’ is getting very small now and there does not seem any prospect of more coming, so as it was in the days of Noah seem fast approaching and the end not far off.

Returning to Fred’s son Philip, he married Jean Vickers (d.2012) who had helped – albeit briefly – to look after two of Winston Churchill’s grandchildren at Hanford House, Dorset during the Second World War.[4] Philip and Jean had two daughters – Carole and Gail. Carole does not recall her father ‘ever condemning anybody for what he may have considered to be wrong’ and thinks he was tolerant of other people’s religious beliefs. As for human nature, Carole thought Mr Noakes would have considered it ‘responsible for both good and bad things: from self-sacrifice right through to wars, and therefore all-encompassing’. Since Mr Noakes was a farmer he was ‘spared the necessity of fighting’ in the Second World War. And while ‘direct combat’ may not have appealed, Mr Noakes was no conscientious objector. Indeed, he served on the home front as a member of Air Raid Precautions which reported and dealt with enemy aerial attacks. All the same, a letter he wrote in 1958 – the year in which both the United States and the United Kingdom conducted a series of nuclear weapons tests – indicates that Mr Noakes was concerned about ‘developments in modern warfare’. ‘Even more horrible’, he thought:

are the recent discoveries in biological sciences, the development of which, it is claimed, will enable scientists to control the hereditary characteristics in human beings – the seed of Reason in its effort to recover that knowledge which was lost when the Angel was banished from God’s presence makes the unacceptable sacrifice – It is near the completion of the circle and the point when God will say: ‘It is finished’.

Mrs Jean Noakes (afterwards Barsley)

Carole and Gail, daughters of Philip and Jean Noakes

Politically a Conservative, Mr Noakes had ‘great respect’ for Winston Churchill. But he held Edward Heath in low regard and did not benefit from the United Kingdom’s 1973 entry into the Common Market. Mr Noakes also had ‘a bookcase full of books’ and seems to have read ‘a lot’, though in private. Significantly, as a surviving trustee of the Muggletonian Church he was in possession of the sect’s archive having transported it to safety after their new meeting room at 74 Worship Street, London had been fire-bombed about 1940.[5] At an unknown date Charles James Crundwell (c.1873–1959), a fellow Muggletonian who lived the last years of his life at Christchurch, Dorset entrusted Mr Noakes with custodianship of this archive and may also have discussed its eventual disposal.

On 12 March 1975 Thompson wrote from his splendid Georgian residence Wick Episcopi at Upper Wick near Worcester to Martin Johnson, expressing his delight and excitement to learn of the possibility that Muggletonian manuscripts might survive. In his characteristically ‘completely frank’ style, Thompson recounted his own prolonged and sustained interest in Muggletonianism, stating:

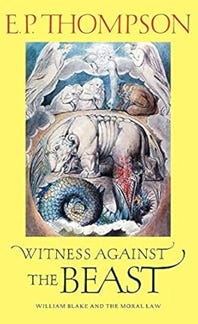

I have developed an admiration for the Muggletonians, a conviction that they have been insufficiently studied and have been misrepresented, and an interest in their doctrines. It is true that a particular aspect of this interest lies in the affinity between certain of their doctrines and some of the ideas of William Blake. And, since Blake must now be acknowledged as one of the greatest men of genius of his time, this suggests that one must take very seriously ideas which may have come to him via [the Muggletonian] Thomas Tompkinson, for example.

After acknowledging that Mr Noakes was the only person who could decide upon what course of action would best preserve the Muggletonian archive, Thompson offered to act on his behalf in discussions with ‘any national institutions’ that might serve as ‘a careful and secure home’ for the manuscripts. Among Thompson’s suggestions were the British Museum, the Bodleian Library and Dr Williams’s Library. But not the Library of the Society of Friends in London since this might be considered inappropriate given the ‘old and very sharp disagreements between the Muggletonians and the Quakers’.[6] Moreover, if Mr Noakes chose to sell ‘some of the books in order the better to preserve the manuscripts’, Thompson again offered to help since he knew ‘a number of honest second-hand booksellers who might advise: and one in particular who is both honest and discreet’. Indeed, Thompson himself ‘would love to obtain copies of any and all of the books listed and would very gladly pay whatever seemed reasonable’. Having discussed possible arrangements for meeting Mr Johnson and Mr Noakes at Easter time, Thompson concluded by reacting positively to the suggestion that a study of the Muggletonians should be written. Since his own particular research interests focussed on the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries he suggested that a friend with specialist knowledge of the seventeenth century would be more suitable to work on the origins of Muggletonianism. This was Dr Bernard Capp, a historian at the University of Warwick (Thompson’s former institution) and author of a book on The Fifth Monarchy Men (1972).[7]

Martin Johnson

Just under three weeks later Thompson had the ‘privilege’ of meeting Philip Noakes and his wife Jean during what was a ‘very pleasant evening’. This was facilitated by Martin Johnson and his wife Gail (Philip and Jean’s daughter) at their home in Leicestershire. Most likely Thompson drove over from Wick Episcopi, perhaps in his ‘hard-wearing Land Rover’. In his posthumously published Witness against the Beast (Cambridge, 1993) Thompson recalled that Mr Noakes was initially ‘cautious but courteous’, adding in private correspondence with Mr Johnson that he did not want ‘to press Mr Noakes too far on the question of his papers and books’. Nonetheless, Thompson was sure that Mr Noakes would ‘make a good decision in due course’. As for the pub Thompson stayed at overnight (‘The Durham Ox’ at Wigston Magna), although it was ‘awful’ he slept perfectly well.

Edward Thompson

At this point in the story, however, the chronology of events provided by Thompson in Witness against the Beast appears somewhat contradicted by other evidence. In short, there is currently a gap in documentation between the beginning of April 1975 and the end of July 1977. Partly this can be accounted for by a year that Thompson spent teaching in the United States (1976–77). At any rate, according to Thompson he was invited to visit Philip and Jean Noakes at their home in Matfield, Kent (a village about six miles from Tunbridge Wells). He was received with kindness and ‘warm hospitality’. In Thompson’s words:

It was a strange situation. Mr Noakes himself was the last repository of a 300-year old tradition. He conversed with me freely about Muggletonian practices and doctrine, which had been carried down to him with a clarity (and, indeed, coherence) which reproduced their seventeenth-century origin. Mr Noakes frequently said ‘We believe’ – and yet one could not point to another believer. There was absolutely nothing of the fanatic or crank in his manner. He was always quiet and concise in his explanations, and I quickly formed a respect for him. On his part he seemed to be pleased that there was a revival of interest in the faith and he did everything he could to help me.[8]

Then on 15 August 1977, or thereabouts, Thompson returned to Matfield. This time Philip Noakes, accompanied by Martin Johnson, took him to Jordan House at Tunbridge Wells. Here, in what Thompson said was a furniture depository, Mr Johnson witnessed Thompson’s ‘great excitement’ as he was shown the Muggletonian archive. These documents were stored in some eighty-odd apple boxes (the original containers Mr Noakes had used to carry them back to his farm during the Second World War). To quote from Thompson’s published account:

Mr Noakes and I spent a long afternoon in the furniture depository, where a somewhat grumpy staff had dragged all eighty-plus [apple boxes] into view in a dimly lit store-room. We started with no. 1. It was wholly made up of nineteenth-century paper-covered reprints of the works of Muggleton and Reeve. And so, on and on, for eighty boxes. Eventually at boxes 80–82 we struck oil. Eighteenth-century bindings appeared, and manuscripts, as well as holograph song-books. I confess that the light was so bad that, when we came to the last box, with trembling fingers I lit a match. I was rewarded by finding in front of me a manuscript by Lawrence Claxton (Clarkson). We managed to get these last three boxes back to Mr Noakes’s house and to inspect them at more leisure. It seemed that all the manuscripts which Alexander Gordon had seen in the 1860s had been preserved.[9]

The next day, following his return to Wick Episcopi, Thompson wrote to Mr Noakes thanking him and his wife again for their hospitality. Acknowledging that their ‘brief inspection of the boxes’ had been ‘quite exciting’, Thompson continued by saying he was convinced that ‘the greatest part’ of the Muggletonian church’s records had been ‘saved intact’ thanks to Mr Noakes’s care.[10] As for next steps, Thompson wished that Professor Douglas G. Greene of the Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia had been with them because Greene knew the seventeenth century material much better than he did. Thompson had even rung Greene’s hotel, but he had returned to the United States.[11] Nevertheless, Thompson’s ‘general feeling’ was that the material which Mr Noakes held was ‘even more important than I had supposed, and that you may well have saved the bulk of the manuscripts’. He could not, however, ‘give a proper opinion without spending several days going through all the apple boxes … in a good reading-light’. That said Thompson was ‘more impressed than before with the hope that the collection’ would ‘eventually find its way to a library where it will be carefully preserved’. Indeed, unless he heard from Mr Noakes to the contrary, Thompson intended to sound out Warwick University in September:

One trouble is that I just cannot say what financial value might be put on the collection, or whether a British library would have the funds to pay. A library would of course be interested above all in the manuscripts, although the books and pamphlets are also scarce.

If you want to hold onto the manuscripts in your own safe-keeping for the time being, but are interested in parting with the books, I don’t know how you would best proceed. In the right hands the books have value – that is, in the hands of a specialised antiquarian bookseller, who specialises in theology, and who distributes a list to libraries and collectors here and in USA … Whatever happens, I am sure you do not need my reminder that THE MANUSCRIPTS MUST NOT BE BROKEN UP: you must not let any bookseller walk off with those boxes without making absolutely sure that they have each been inspected for manuscripts, and then these have all been gathered into your own keeping, pending their final destination.

In response to Mr Noakes’s remark about selling the entire manuscript collection, Thompson advised that it could be auctioned through Sotheby’s although the process was likely to be extremely slow. Nor could he say ‘what price they would fetch: it would depend somewhat upon whether more than one well-endowed (probably American) library was bidding’. But Thompson hoped it wouldn’t come to this: ‘I don’t much like the idea of the records leaving this country’ even though ‘American libraries are excellent’. Finally, Thompson added ‘a few additional comments’ regarding a Muggletonian book list: most could be consulted in the British Museum or the Bodleian, ‘but in very few other libraries’. He also referred to ‘the importance of the oil paintings and in particular of the Large Commission Book’. Furthermore, since Thompson was keen on ‘finding out how far William Blake’s “Songs of Innocence” may have been written within a Muggletonian tradition (indeed, I wonder whether Blake himself may have been a Muggletonian Friend)’, he would be ‘most interested in seeing the exercise books with songs &c., as well as the names of members in any accounts before about 1840’.

The same day that he wrote to Mr Noakes (16 August 1977), Thompson penned some further thoughts to Mr Johnson regarding what to do with the Muggletonian archive. From what Mr Noakes said to Thompson:

I rather think that he feels it is his right policy (in the interests of the family) to sell the manuscript collection – that’s fine, but if that is his decision, then I rather think that the sooner it is done the better (unless he wishes to keep them all together in his own hands). So often valuable collections have been lost by fire or stupidity in repositories, &c.

As for the books, Thompson thought that they were ‘worth a bit, but not as much as all that, because any bookseller is going to take a good 50% whack out of them (and will try to get away with giving even less); and yet one is powerless to sell them without a bookseller’s facilities and lists’.

Going back to Thompson’s published account he related that ‘Mr Noakes had preserved some of the most interesting documents in his own home. These included three large guard books with papers and correspondence of the London Church’. The reference here seems to be to the contents of the last three apple boxes (80–82) that had been retrieved from the depository at Tunbridge Wells on roughly 15 August. According to Thompson, ‘with extraordinary goodwill and trust’ Mr Noakes allowed him to carry off these documents for a short time, ‘to study and xerox’.[12] This Thompson did in the first week of September 1977. Indeed, he went so far as to prepare a detailed description of the ‘quite remarkable collection’ stored in ‘three apple boxes’ that were kept ‘on the owner’s shelves’. This 13-page inventory he entitled ‘Records and archives of the Church of Believers in the Commission of the Spirit (Muggletonians) circa 1660 – circa 1930’. The inventory begins with a brief history of the Church followed by a summary of Mr Noakes’s situation:

He is now anxious that [these books and papers] be preserved (and made available to scholars) in one of the world’s major libraries, preferably in England … he is unable to donate the records (he has incurred very considerable expenses in 35 years of storage, &c.) but at the same time he does not wish to expose the collection to the risk of public auction to a random buyer, such as a dealer who might break it up. He will therefore give serious consideration to a fair offer from a major British institution. At the same time he has copies of nearly all published Muggletonian works, and will be ready to assist any library to complete its own holdings.

Thompson ‘listed the manuscripts under four classes’:

1. Letters and memoranda

2. MS copies of Muggletonian works, published & unpublished

3. Songbooks

4. Records and accounts of the Church

Regarding the three large guard books, which consisted of loose manuscripts, Thompson believed that they offered ‘the most important consecutive record of the history of the Church’. He also noted that during the Second World War Fred Noakes ‘occupied himself with taking a copy of other letters and documents in his possession’. There were ‘two substantial volumes of these copies’. Regrettably, once they had been transcribed ‘the original letters were then destroyed’.

As for the Songbooks, Thompson noted that:

Muggletonians had very few forms of service: no prayer, no preaching. They met socially, for song and discourse, in private rooms in public houses. At these meetings divine songs were sung, often to the popular tunes of the day. This enabled them, in the times of persecution, to pass themselves off as a drinking club.

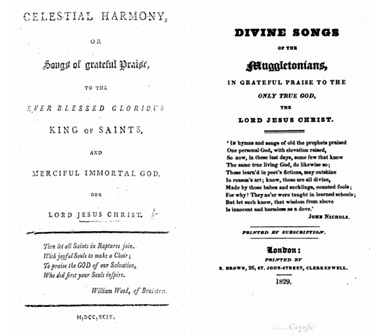

The only published songbook that he had seen was Divine Songs of the Muggletonians (1829), although he suspected that there may have been a songbook published earlier in the 1790s called Songs of Grateful Praise. However, he had never seen a copy of this work.

Left: Celestial Harmony, or Songs of grateful Praise (1794)

Right: Divine Songs of the Muggletonians (London, 1829)

On 6 September Thompson wrote to Mr Noakes enclosing ‘the list’ – presumably his inventory – for comments. Since Thompson was taking advice from a couple of friends he suggested waiting until the end of the month before doing anything. As for the printed books, Thompson generously offered his help. It had occurred to him that Mr Noakes ‘might wish to sell them directly’. If so, this might be possible if Mr Noakes ‘prepared a careful list of each item in your holding, whether bound or paper, &c. (but not of course indicating how many copies), and duplicated your own catalogue’. He then outlined a range of possibilities before finishing by thanking Mr Noakes for kindly giving him a collection of Muggletonian works: ‘It’s a very fine set of all the publications’. Having been through them carefully Thompson thought he was only missing Muggleton’s Acts of the Witnesses. He offered to gladly buy one if Mr Noakes had any spare copies.

Meanwhile, Martin Johnson had written to Anthony Garnett, an antiquarian bookseller based in St Louis, Missouri and the brother of his colleague Emmeline Garnett. Mr Garnett responded on 3 September 1977 saying that he was under the impression that the ‘Muggletonian library’ had in fact ‘already been disposed of’. Even so, he was ‘sure it would be relatively easy to find a home for the main part of the collection (manuscripts and so on)’ since there were ‘many people interested in all varieties of sects and dissenters’. I will return to what happened to the Muggletonian printed books in the third and last part of this essay. But beforehand there is the fate of the manuscripts to conclude.

On 21 November 1977 Mr Noakes wrote to Mr Johnson informing him that a Dr Waley was arranging for someone from the London firm of Bernard Quaritch, specialists in rare books and manuscripts, ‘to come down and value the manuscripts’. For the moment, the only available account of what happened next is that offered by Thompson in Witness against the Beast, although there are discrepancies with the evidence provided here. Thompson was understandably keen to steer the archive to a national library:

But here we met with a difficulty. Muggletonians eschewed evangelism unless by the printed word. It was in print that the faith must be preserved, and through which conversions might be made. Mr Noakes was willing to let the archive pass to a library, but on condition that the library housed also all the Muggletonian reprints and circulated libraries in the English-speaking world offering to supply copies. This proved to be too large a commitment for any library which I approached to accept.[13]

According to Thompson, he returned from the United States in 1977 to learn ‘with dismay that Mr Noakes had been seriously ill with angina’ and was willing to ‘forego his previous conditions’. After some hesitation regarding whether Mr Noakes had the right ‘to dispose of the Church’s property’, the British Library agreed to purchase the manuscripts together with examples of the more important printed texts on 23 January 1978.[14] Deposited and arranged in eighty-nine volumes (Add. MSS 60168–60256), the collection has since been supplemented with nineteenth-century copies of Muggletonian prose and verse (Add. MS 61950) and copies of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Muggletonian correspondence (Add. MSS 79756–79759).

Some years later looking back through his files ‘concerning this matter’, Thompson was ‘surprised to be reminded as to how much time and labour were expended in inspecting, recording and guiding the archive to its haven, and the formidable volume of correspondence it generated’. Yet it was ‘all sweetened’ by recalling the kindness shown to him by Jean and Philip Noakes. For it had indeed been ‘a privilege to have been taken into the confidence of “the last Muggletonian”’.[15]

Philip Noakes

Philip Noakes died on 26 February 1979. Apparently it was ‘a source of great satisfaction’ that Thompson had befriended him and that the archive had been ‘appropriately recognised and made available to future historians’. But was he actually the ‘last Muggletonian’? Perhaps not, since it is known that three women survived him who might be considered Muggletonians. All were distant relations, although Mr Noakes’s widow said that he did not regard them as believers. One was Eva Jordan (1892–1985), the daughter of a Faversham garage owner who had apparently attended Muggletonian meetings before the Second World War. Sadly she suffered from senility in later life. Another was Minnie Amelia Marian Wilson (b.1919), daughter of an Essex police constable. She used to spend a considerable amount of time discussing matters of faith with Mr Noakes. The third woman was the mother of Eva or Minnie who died in her nineties. There is also a Wade Muggleton who in the late1980s, along with other members of his family, claimed – perhaps facetiously – to be a Muggletonian. And that is to say nothing of anyone who might have chosen to keep silent.

[1] Christopher Hill, Barry Reay and William Lamont, The World of the Muggletonians (London, 1983), pp. 1–5; E.P. Thompson, Witness Against the Beast. William Blake and the Moral Law (Cambridge, 1993), pp. 115–19; William Lamont, Last Witnesses. The Muggletonian History, 1652–1979 (Aldershot, 2006), pp. 7–8.

[2] The remainder of this account is based on personal email exchanges more than eighteen years ago, as well as copies of relevant correspondence. I am most grateful to Michael Cole, Anthony Garnett, Emmeline Garnett, Martin Johnson, William Johnson, Carole Noakes, Kevin Repp and Simon Routh for their generous help in answering my research enquiries.

[3] The identity of Thompson’s friend is unknown. It was not Emmeline Garnett since she did not know Thompson. So it may be that here Thompson misremembered the circumstances of how Martin Johnson came into contact with him.

[4] Julian Sandys (1936–1997) and Edwina Sandys (b.1938), two of the three children of Diana Churchill and Duncan Sandys.

[5] The Muggletonians had moved to these new premises by 1924 because the lease of 7 New Street, Bishopsgate had expired and they could not afford to purchase the property.

[6] In a further letter to Martin Johnson the following day (13 March 1975) Thompson added: ‘On looking back through my notes I see that the controversy between the Quakers and the Muggletonians in the early days was very bitter indeed: and it would therefore be quite inappropriate for any of Mr Noakes’s collection to find itself in the Library of the Society of Friends … Therefore I withdraw this idea altogether, and apologise for such an inappropriate suggestion’.

[7] Bernard Capp does not recall Thompson ever mentioning the Muggletonians to him, although he remembers that Thompson ‘certainly had an interest in the radicals of the 1640s and 50s, and we discussed them briefly from time to time’.

[8] Thompson, Witness Against the Beast, pp. 115–16.

[9] Thompson, Witness Against the Beast, pp. 116–17.

[10] Writing to Martin Johnson on the same day (16 August 1977, Thompson added: ‘the more I think over what we saw in that repository the more convinced I am that Mr Noakes has saved the central body of the Church’s archives. This was not clear to me from the earlier lists’.

[11] Greene would publish ‘Muggletonians and Quakers: A Study in the Interaction of Seventeenth-Century Dissent’, Albion, 15 (1983), pp. 102–22. Thompson is thanked in the acknowledgements.

[12] Thompson, Witness Against the Beast, p. 116.

[13] Thompson, Witness Against the Beast, p. 117.

[14] Thompson, Witness Against the Beast, pp. 117–18.

[15] Thompson, Witness Against the Beast, p. 119. Both Jean and Philip Noakes are thanked in the preface to Witness Against the Beast, p. xiii.

That man, Mr. Noakes sounds like a splendid fellow!

It is interesting how there is a tendency among those who self-consciously adopt a minority position (particularly by going into separation), despite being regarded as radical, at least by some, to travel in what one might call a more conservative direction.

The same is certainly true of some people in the post-reformation English Catholic community.

What a poignant and arcane adventure into a lost past.