The Ranters – part two

II. Identifying the Ranters

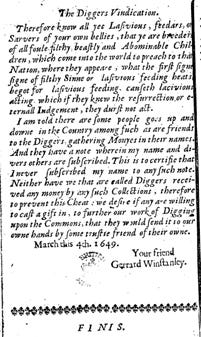

During the Parliamentarian campaign in Ireland, Oliver Cromwell referred in a letter of 14 November 1649 to ‘great ranters’ among the enemy between Dublin and Wexford, which his nineteenth-century editor Thomas Carlyle took to mean braggarts. This usage, though unusual, indicates that the noun ranter then described a way of speaking. It surely derived from the verb to rant, meaning to talk or declaim in an extravagant or hyperbolical manner, or to speak furiously. In early 1650 Gerrard Winstanley warned women to beware of the ‘ranting crew’, refuting the accusation that ‘the Digging practises, leads to the Ranting principles’. Clearly the Diggers’ spiritual and temporal community, with its open fluid membership, had been infiltrated by what Winstanley was shortly to call ‘Ranters’, and in a subsequent vindication he disassociated the Diggers from them, giving some reasons against ‘the excessive community of women, called Ranting’ (dated 20 February 1650, with postscript 4 March 1650).

Gerrard Winstanley, A Vindication of those Whose endeavors is only to make the Earth a common treasury, called Diggers (1650)

Winstanley defined the ‘Ranting Practise’ as ‘a Kingdom without the man’, a corrupting carnal realm of the five senses that lay in the ‘outward enjoyment of meat, drink, pleasures and women’. It was therefore not the spiritual kingdom of heaven – interpreted as Christ within – but the Devil’s kingdom of darkness, full of unreasonableness, madness and confusion. Excessive copulation with women dissipated male vitality, resulting in unwanted pregnancies and the destruction of harmony within the patriarchal household. ‘Ranting’, moreover, begat idleness and this evil had to be prevented with righteous communal labour. Significantly, Winstanley’s pamphlets contain the earliest known use of the words ‘Ranting’ and ‘Ranter’ in this sense. Afterwards, ‘Ranters’, together with its variants ‘Raunters’, ‘Rantors’ and ‘Rantipoler’, appears in several newsbooks (weekly booklets that were the ancestor of daily newspapers) and other sources from late June 1650, while ‘ranting’ occurs in newsbooks and sermons from early August. In addition, ‘Rantism’ was used from 1653, as was ‘Ranterism’.

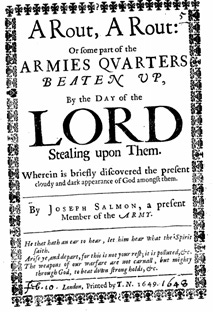

As for those called Ranters by their contemporaries, and of whose existence we can be confident, it must be stressed that there are noticeable discrepancies in how this pejorative label was deployed and no consensus as to its exact meaning. Indeed, by imputing a set of odious characteristics onto those designated Ranters, the person adopting the term often unwittingly revealed something about his – or very occasionally her – own anxieties. Nevertheless, Jacob Bothumley (1613–1692), Lawrence Clarkson (c.1615–1667?), Abiezer Coppe (1619–1672), Joseph Salmon (fl.1647–fl.1682?), the minister Thomas Webbe (c.1625–fl.1660?), and the preacher Andrew Wyke (fl.1645–fl.1663) were all considered Ranters during particular phases of their lives. Coppe, Clarkson and, to a lesser extent, Salmon and Bothumley, were acknowledged by polemicists and subsequently several Quakers as their ringleaders.

Joseph Salmon, A Rout, A Rout (1649)

Between 1648 and his release from Newgate prison about July 1651, Coppe can be connected through encounters, correspondence, prefatory epistles and publications, with Giles Calvert (publisher and bookseller), Lawrence Clarkson, Richard Coppin (preacher and author), James Cottrell (printer), John File (author), John Gadbury (astrologer), Mr Maule (of Deddington, Oxfordshire), Thomasine Pendarves (of Abingdon, Berkshire), John Pordage (rector of Bradfield, Berkshire), Joseph Salmon, William Sedgwick (millenarian preacher), Mrs Seney (matron of the Savoy Hospital carted through the streets of London for prostitution), Mrs Wallis (Wyke’s kinswoman), Thomas Webbe and Andrew Wyke. Coppe was most likely also associated with William Bray (imprisoned army officer accused of being a Ranter and being in bed with two women together at Seney’s residence). In addition, Coppe reportedly had an unknown number of followers, several of whom had probably been one-time members of Baptist congregations meeting at London (St Helen’s Bishopsgate), Gloucestershire (Little Compton, near Moreton-in-Marsh), Oxfordshire (Hook Norton), and Warwickshire (Coventry, Easenhall, Southam, and Warwick). According to Clarkson, moreover, while in London about January 1649, Coppe had appeared in a ‘most dreadful manner’ before a spiritual community known as ‘My one flesh’.

Lawrence Clarkson, The Lost sheep found (1660), p. 24

Known to Calvert, they seem to have gathered secretly on Sundays at the homes of the group’s various members. ‘My one flesh’ consisted of, among others, Mr Brush, Mr Goldsmith, Sarah Kullin, Mary Lake (blind ‘chief speaker’), Mr Melis (possibly John Millis, brown baker living on Great Trinity Lane), William Rawlinson (who knew of Salmon), Mrs Rawlinson, and Mr Watts. Another spiritual community, either overlapping or sharing things in common with them, appears to have included W.C., J.H., William Sedgwick and Edward Walford (a messenger of the House of Commons); another still included Margery Castle, John Radman (army agitator turned mutineer and ‘great Raunter’), and Valentine Sharpe.

A Perfect Diurnal, no. 17 (1–8 April 1650), p. 181

For his part Clarkson, an itinerant Baptist preacher turned self-styled ‘Captain of the Rant’, had conferred with William Sedgwick and the Welsh preacher William Erbury (later charged with saying that the Ranters had been the holiest people in the nation). Clarkson counted Dr Barker, Major William Rainsborough (brother of the murdered Leveller martyr Thomas Rainsborough), and Mr Wallis among his ‘disciples’.

Flag device of Major William Rainsborough, depicting the severed head of Charles I, accompanied by a motto taken from Cicero: ‘salus populi suprema lex’ [The welfare of the people should be the supreme law]

Although a married man, Clarkson also claimed that a Mrs Mary Middleton and a Mrs Star were in love with him, engaging in an adulterous liaison with the latter. After disrupting the Digger plantation on the Little Heath in Cobham, Surrey he was eventually apprehended with several ‘Raunters’ allegedly openly ‘satisfying their lusts’ like ‘lascivious beasts’ at ‘The Four Swans’, near Whitechapel in mid-July 1650. Mary Middleton of Clarkson’s ‘old society’ was doubtless the Mrs Middleton who, with one or two others, narrowly escaped arrest when a group of Ranters were seized on 1 November 1650 at her husband’s house at the ‘David and the Harp’ on Moor Lane, St. Giles Cripplegate. The remainder were caught and committed to Bridewell for indecency, blasphemy, swearing ‘Ram me, Dam me’, and singing filthy songs to the tune of the Psalms. They were Walter Albone, John Collins, William Groome, William Holt, William Reeve (possibly brother of the heresiarch John Reeve), William Shakespeare, and Henry Wattleworth. While in Bridewell they may have become acquainted with the former Digger and suspected sorcerer William Everard, since many of ‘Ranting Everard’s party’ were reportedly ‘lunatic, and exceedingly distracted’.

Anonymous, The Routing of the Ranters (1650), pp. 4–5

Another group commonly supposed to be Ranters were the followers of John Robins, whom they believed to be ‘the God and Father’ of Jesus Christ while Joan, his reputed spouse, would give birth to the Messiah. Another still were apprehended in London for ‘disorder and uncivil carriage’ on 2 January 1651. Other suspected or supposed Ranters, though this is not an exhaustive list, included; James Claphamson; John Norris; Thomas Willett (found dancing naked with a woman); two ‘naked Ranters’ disrupting a church service at Hull; and a ‘company of ranting sluts’ detained in Bridewell.

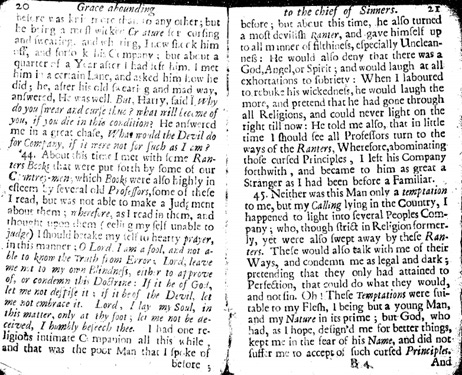

Several Parliamentarian soldiers were also accused of being Ranters, associating with Ranters or holding blasphemous opinions consonant with Ranterism; William Covell (captain in Thomas Fairfax’s regiment of horse); Francis Freeman (captain in Colonel John Okey’s regiment of dragoons); Edward Leak (cornet in Major Grove’s troop, which originally had ‘many persons of subtle Ranting Principles’); Nathaniel Underwood (said to have been a cornet in Oliver Cromwell’s regiment); and two troopers of Colonel Nathaniel Rich’s regiment. In the provinces there were suspected Ranters in Dorset, Ely (where Sedgwick had been a minister until September 1649) and Towcester (Northamptonshire), while spiritual communities akin to Ranters existed at Godmanchester (Huntingdonshire) and Abingdon (Berkshire). Furthermore, the tinker John Bunyan (1628–1688) remembered having read a few of the ‘Ranters Books’ that were distributed in Bedfordshire and highly esteemed by several old professing Protestants. Suggestively, a separatist congregation was established at Bedford about 1650. There were also General Baptist churches at Fenstanton and Warboys (Huntingdonshire). The Warboys church book contains a condemnation of the Ranters’ ‘wicked practices’, while emissaries from Fenstanton later confronted individuals at Kingston (Cambridgeshire), Newport (Essex), and Dunton (Bedfordshire) whose doctrines ‘savoured of Ranterism’.

John Bunyan, Grace abounding to the chief of sinners (1666; 1698 edition), pp. 20–21

The Muggletonians regarded Lawrence Clarkson, Mistress Cook, Nathaniel (dung eating prophet known as ‘Shitten Nat’), Isaac Penington (future Quaker), Mr Pope, the pedlar Stephen Proudlove (formerly an alleged member of the ‘family of the mount’), William Reeve (the heresiarch John’s brother), Mr Remington, William Smith (future Quaker), and TheaurauJohn Tany (self-proclaimed High Priest and Recorder to the thirteen Tribes of the Jews) as Ranters. In addition, Lodowick Muggleton recalled mingling and disputing with Ranters in London, who at that time were ‘very high in Imagination’. For their part, the Quakers considered a number of people to be Ranters including, though again this is not comprehensive; Rose Atkins, Jacob Bothumley, Jonas Browne, Thomas Burdhall, Thomas Bushel, John Chandler, Abiezer Coppe, John Flower, Thomas Ford (of Staffordshire), Bess Hodgkin, William Lampitt (of Ulverston, Lancashire), Mr Mills, Blanche Pope, Joseph Salmon, Mary Todd, Timothy Travers and Robert Wilkinson (of Leicestershire, possibly the author of that name). They disputed with what they took to be Ranters at various meetings in London, Leicestershire (Swannington) and Warwickshire (Edge Hill), and wrote of Ranters in counties south of London as well as in Cornwall (Looe), Derbyshire (Kidsley Park, the Peak District), Dorset (Weymouth), Hampshire, Leicestershire (Leicester, Twycross), Norfolk (Norwich), Northamptonshire (Wellingborough), Rhode Island (Providence), Staffordshire (Basford, Leek), Sussex, and Yorkshire (Cinder Hill Green, Cleveland, Staithes, York).

Although several journalists fabricated authorial personas as former Ranters or claimed to have witnessed Ranter gatherings to authenticate their sensationalist accounts (John Holland, ‘J.M.’, J[ohn] R[eading?], ‘Gilbert Roulston’, ‘Timothy Stubs’, ‘Samuel Tilbury’), no actual Ranter embraced this ignominious characterisation. All the same, just as those cultivating St. George’s Hill referred to themselves as Diggers and some scornfully called Quakers declared themselves to be Children of Light, so a few people branded Ranters or, more rarely, High Attainers styled themselves the Mad Crew.

This ‘mad ranting crew’ were accused by the London minister Robert Gell of pretending to be ‘God’s peculiar people’ and of believing that they had ‘happy and blessed unity and community’ with God and, crucially, ‘among themselves’. Significantly, leading Ranters such as Coppe and Clarkson also developed a strong sense of group identity, regarding themselves as members of a spiritual community. Thus Coppe believed that he had been shown ‘a more excellent way’ beyond church fellowship with his Baptist brethren, owning ‘none but that Apostolical, Saint-like Community spoken of in the Scriptures’, while Clarkson described himself as ‘one of the Universality’.

Identifying the Ranters is, in short, a contentious exercise. There was (and is) no agreed definition. Furthermore, not all contemporary ascriptions should be accepted. On the one hand there was lumping: uninformed polemicists tended to invent, exaggerate and conflate for self-serving ends. On the other, an impulse for splitting: former co-religionists and opponents within the same milieu were anxious to disassociate themselves from the Ranters by accentuating doctrinal and behavioural differences. Both tendencies have been reflected in the historiography. And while both approaches have their merits and limitations, it might be better to reconceptualise the Ranters as an assortment of spiritual and temporal communities, sometimes overlapping and given added cohesion by their adversaries. At their heart were Coppe, Clarkson and their adherents, although it is noteworthy that other groups such as the one centred around Bothumley seem to have existed independently. Marked variations notwithstanding, they generally shared similar origins and characteristics.

Next we will look at the Ranters’ origins as well as how they were seen by their contemporaries.

.