In the previous post I talked about my contribution for a collection of short stories published by Comma Press. Here I would like to revisit my first involvement with Comma Press. This was for another set of short stories first issued in hardback in 2017 and then reprinted in paperback the following year. Entitled Protest - Stories of Resistance it was edited by Ra Page. He wanted to follow up on an impulsive feeling, namely – in the vein of British Marxist historical writing on what might be called the ‘canonical radical tradition’ – that:

rather than a series of discrete identity struggles, British protests form a continuum; one where ideas, tactics and philosophies can be seen flowing between movements, triggering new conversations, inspiring and shaping new methods.

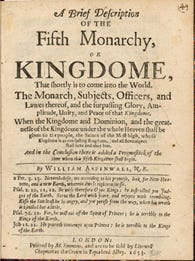

The authors of the short stories commissioned for this project were encouraged to ‘steer clear of political leaders, the “heroes” of the history books’. Altogether, there were twenty contributions, each with an afterword provided by an historian, sociologist or similar. My collaboration was with the screenwriter and novelist Frank Cottrell-Boyce, the current Waterstones Children’s Laureate. In a long telephone conversation it soon became clear that Frank wanted to do something a bit different. To tell a tale about those who, outside academic circles, are little remembered today. So rather than the Diggers – who do feature in Protest – I came up with the Fifth Monarchists. Frank’s story, ‘A Fiery Flag Unfurled in Coleman Street’ is brilliant. What follows is a slightly adapted version of my afterword which, like my post on Martin Marprelate, first appeared in the earliest days of this blog.

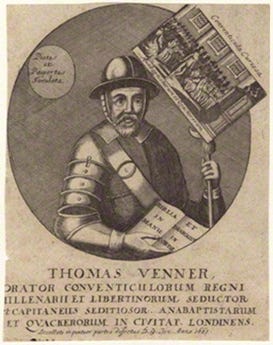

Framed by the Great Fire of London of 2–5 September 1666, ‘A Fiery Flag Unfurled’ focusses on events from December 1660 to January 1661 when, for several days, the capital became the scene of a bloody insurrection. The rebels’ intention was to depose the recently restored Stuart monarch, Charles II and replace him with another king: Jesus. But they failed. There were roughly thirty survivors of this armed uprising, of which thirteen were publicly executed. These rebels believed in an imminent apocalypse and were called Fifth Monarchists. Their leader was Thomas Venner.

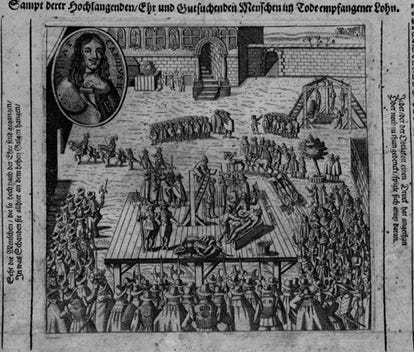

Relation auß London vom 4. Febr. 1661, detail showing execution of Thomas Venner

Before looking in more detail at the Fifth Monarchist risings of April 1657 and January 1661, it is worthwhile recapping what had happened during the preceding twenty years. Pre-publication censorship had effectively broken down, with the result that more than 33,000 printed titles were issued between 1640 and 1660. Courts which had facilitated the exercise of royal power were abolished by act of Parliament. There was bloody rebellion in Ireland and then devastating Civil Wars throughout the British Isles. An estimated 80,000 soldiers were killed or maimed out of a population of probably no more than 5.3 million. The Archbishop of Canterbury was executed, bishops deposed and the Church of England stripped of its authority. For the first and only time in English history a reigning monarch was put on trial, charged with treason and publicly executed.

The execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649

A Commonwealth was declared and the House of Lords abolished. Most of the Royalists who had supported Charles I were disarmed. Some were imprisoned and a few executed. Many more had to pay fines to keep hold of their homes and property. As for the Crown and the Church, much of their land was confiscated and sold off. The biggest beneficiaries were army officers on the winning Parliamentarian side who bought up large estates on the cheap. Meanwhile some regiments began to mutiny over arrears of pay. But there were also the widows and orphans of slain combatants who had to beg to survive. So too did the wounded. Bad weather did not help. There was famine as harvests failed, animals died and humans succumbed to plague. To paraphrase a couple of contemporary pamphleteers, the old world had been turned upside down and was burning up like parchment in the fire.

Yet with the king defeated the winners began arguing among themselves as to how the kingdom should be governed. Within this vacuum new political movements and religious communities emerged. Among the best known are the Levellers, who demanded social justice and the introduction of religious toleration; the Diggers, who were essentially pacifists as well as communists; the Ranters, who believed that individuals were free to do as they wished since sin had been abolished; and the Quakers, who were initially more transgressive and provocative than their modern counterparts. Many believed that the Apocalypse was imminent and that Jesus Christ would come back to reign on Earth. Using a combination of the bible and cutting edge mathematics they calculated the promised date as 1650 or 1656. Then, when those prophecies failed, they fixed on 1666; that is a millennium (1000) + the number of the beast (666). It’s here that the Fifth Monarchists come in.

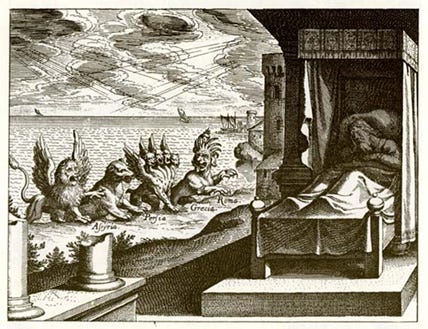

Their name was taken from Daniel. This biblical book is set in ancient Babylon at the time of Kings Nebuchadnezzar and Belshazzar, although it was actually written much later in the mid-second century before Christ. Parts of it relate various dreams and visions concerning a statue made of different materials and four great beasts. Taken together they were usually interpreted as four world empires: (1) Babylon; (2) the Medes and Persians; (3) Greece; (4) Rome. All would be destroyed, after which there would be a fifth monarchy ruled by King Jesus.

Daniel’s Vision of the Four Beasts; engraving by Matthäus Merian the Elder, 1630

Since they were not an organised religious community like the Baptists or Quakers it’s difficult to date the precise beginnings of the Fifth Monarchists. But winter 1651 – shortly after Oliver Cromwell had defeated the enemies of the new republic in Ireland, Scotland and England – seems about right. Certainly by 1653 the press was full of accounts about Fifth Monarchists meeting at several London locations.

Thereafter the movement spread, particularly in southern England. Outside the capital support was concentrated in Suffolk, Norfolk, Devon, Cornwall and North Wales. Yet even allowing for exaggerated reports at the height of their popularity there were probably less than 10,000 Fifth Monarchists. By comparison, there were perhaps as many as 25,000 Baptists and 60,000 Quakers in 1660.

Besides the cry ‘no King but Jesus’, Fifth Monarchists were also interested in Jewish law. The most extreme adopted Jewish rituals and customs – dietary regulations, circumcision and celebrating the Sabbath on Saturday. Among the mainstream there were demands for the revival of the Sanhedrin, an ancient Jewish law court which was seriously considered as the model for Parliamentary government in 1653. It’s also worth mentioning in this context that in 1656 Jews were tacitly readmitted to England. They had been expelled in 1290 and Cromwell had to overcome widespread opposition so as to turn a blind eye to their presence. Potential economic benefits were a factor, but more important was hastening the coming of King Jesus by creating a first-hand opportunity to convert Jews to Protestantism. 1656 it should be remembered was the predicted year when Christ would begin reigning on earth with his so-called saints. Beforehand, however, anti-Christ had to be defeated and the world destroyed by fire. To speed things along, and in a foreshadowing of the Great Fire of 1666, the followers of TheaurauJohn Tany (1608–1659), a one-time puritan claiming to be the High Priest of the Jews deliberately burned a number of buildings in London causing thousands of pounds of damage.

Then in April 1657 there was a minor rising against Cromwell’s Protectorate. It was instigated by a Fifth Monarchist faction who regarded Oliver as little better than an uncrowned dictator propped up by an unsteady alliance of local magistrates, obedient ministers and large sections of the army. Among the Fifth Monarchist plotters was Thomas Venner (c.1608–1661), a cooper with artillery training who had spent time in Massachusetts.

The rebels’ standard was ‘a fiery flag’: a red lion resting on a white background bearing the motto ‘Who shall rouse him up?’ (Genesis 49:9). This image signified the ‘Lion of the tribe of Judah’ and was probably intended as a reference to the second coming of Jesus (Revelation 5:5). The rebellion, however, was a disaster. Thanks to a well-organised government surveillance system it was swiftly crushed with no recorded loss of life. The newsbook Mercurius Politicus provides a summary of events:

Whitehall, Thursday, 9 April 1657

Discovery having been made of an Insurrection intended by a sort of people and that they intended to begin this night, and it being discovered that some of them were met together at a certain house in Shoreditch, order was given to apprehend them; the Soldiers and Messengers employed found there about 20 persons ready armed, booted and spurred, intending to have been at their appointed rendezvous, this night, upon Mile End Green near Whitechapel, about 9 of the clock, where others of their party were to have met them. When they were apprehended there were arms seized with them in the house, and several hampers of arms had been conveyed to certain places in the field near the place appointed for rendezvous, together with printed books and copies of Declarations fitted for their design ... From thence (it is said) they meant to have marched 8 miles this night into Essex, and to have directed their course towards Norfolk.

Venner was imprisoned without trial in the Tower of London where he remained until at least 28 February 1659.

Oliver Cromwell died on 3 September 1658, the anniversary of his two great military victories at Dunbar and Worcester. He was the man who had held it all together and within nine months the Protectorate of his son and successor Richard had unexpectedly collapsed. The restored Rump Parliament which replaced him fared little better, lasting less than a year. On 25 April 1660 a new Parliament assembled. Known as the Convention Parliament it consisted of both a House of Commons and a re-established House of Lords. A month later on 25 May Charles II returned from exile, landing at Dover. On 29 May, his thirtieth birthday, he entered London.

Triumphal procession of Charles II

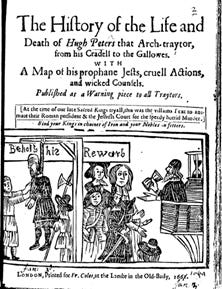

Immediately the restored monarch set about securing power. Potentially disloyal army regiments were disbanded, the militia resettled and a royal bodyguard created. A new royal administration was formed. Although important posts were granted as rewards to staunch royalist supporters, Charles’s government nonetheless featured former Cromwellians who had shrewdly swapped sides. Royalists were also put in charge of local government and key urban areas. With his enemies purged the king decided against a bloodbath. Instead he pursued a policy of reconciliation to heal his wounded kingdoms. Those implicated in his father’s trial and execution, however, were shown little mercy. Ten regicides, including Major-General Thomas Harrison (1616–1660) and the preacher Hugh Peter (1598–1660), were publicly hung, drawn and quartered in October 1660. Others were imprisoned or fled abroad.

On 30 January 1661, the twelfth anniversary of Charles I’s death, Oliver Cromwell’s body was exhumed and posthumously beheaded together with that of his son-in-law, Henry Ireton (1611–1651), and two other hated regicides.

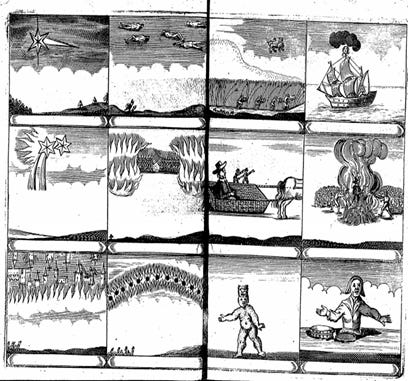

Despite deep divisions quite a few opponents of the Restoration regime united against a common enemy under the banner of the ‘Good old Cause’. They interpreted their devastating defeat as God’s harsh judgement against their failings: ‘the Lord has blasted them and spit in their faces’ as one contemporary put it. Even so, they regarded this terrible change in their fortunes as a temporary setback before God granted them ultimate victory. Disaffected Cromwellian army officers, alienated republicans, disgruntled nonconformist preachers and discontented printers therefore began to form clandestine alliances. The results ranged from ill-fated plots and insurrections to the secret publication of incendiary pamphlets including collections of prophecies, portents and natural disasters interpreted as signs of the Stuart monarchy’s impending destruction.

Mirabilis annus, or, The year of prodigies and wonders being a faithful and impartial collection of severall signs that have been seen in the heavens, in the earth, and in the waters

Although fearful of this radical underground the government infiltrated it with a highly effective network of spies and agent provocateurs. Enemies of the state were flung into prisons where many died or were debilitated because of the noxious conditions.

It’s against this volatile backdrop that we can situate Thomas Venner’s second attempt at armed rebellion on Sunday, 6 January 1661. Pamphlets, newsbooks, letters, diaries, memoirs, chronicles and court records enable us to partially reconstruct events. Setting out from their meeting house in Swan Alley in Coleman Street, ‘that old nest of sedition’, about fifty heavily armed Fifth Monarchists marched on St. Paul’s cathedral where they demanded the keys from a bookseller. There they shot a man who declared for King Charles rather than King Jesus. With the alarm raised the city guard sent musketeers against them but they were put to flight. London’s mayor then led a troop of reinforcements. Outnumbered the bulk of the Fifth Monarchists retreated towards Aldersgate. After killing a constable they withdrew to Kenwood, situated between Highgate and Hampstead.

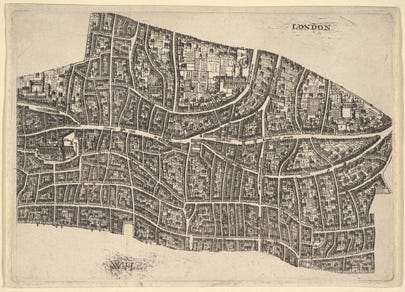

The city of London [detail] before the Great Fire of September 1666

On the morning of Wednesday, 9 January, weakened by hunger, they entered London again. Once in the city the Fifth Monarchists seem to have split into groups or else were reinforced by a contingent coming from London Bridge. Venner’s party intended to capture the mayor in his bed but were attacked by a company of the trained bands in a fierce engagement at Cheapside. They withdrew into Wood Street, holding it for about fifteen minutes. During this skirmish Venner wielded a halberd with which he killed three men.

Perhaps during a lull in the fighting Venner and some companions entered Wood Street Compter (a small gaol within the City of London). There they demanded the release of prisoners – presumably seeking reinforcements. They were then fired upon by troops under the command of Major (or Lieutenant-Colonel) Cox. Venner was seriously wounded and appears to have been captured at this point. The survivors fled and dispersed. Some were chased to a locked postern gate in London Wall. With escape impossible between seven and ten holed up in an upper-room at the ‘Blue Anchor’ alehouse near Cripplegate. Cox’s men surrounded it before climbing up an adjoining roof. They then threw off the tiles and fired inside at the same time shooting down the door and storming up the stairs. Five or six Fifth Monarchists were killed before the remainder surrendered. Others may have joined up with a different band still loose in the city since a bloody engagement was also recorded at the upper end of Bishopsgate Street. Here some Fifth Monarchists took refuge in an alehouse called ‘The Helmet’. Having withstood two volleys of musket fire and two charges these rebels routed after taking casualties when hit by yet more shots.

Altogether there were about thirty survivors of Venner’s rising. Twenty five, including seven wounded, were captured and imprisoned in Newgate. However, at least four escaped.

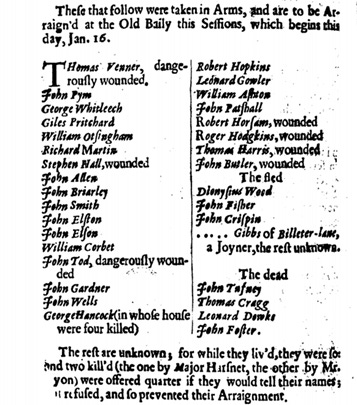

Mercurius Publicus, no. 2, 10-17 January 1661, p. 32

According to the diarist and naval administrator Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) their battle cry had been ‘The King Jesus, and the [regicides’] heads upon the gate’. At their trial at the Old Bailey sixteen were found guilty and four acquitted. On Saturday, 19 January 1661 Venner and another ringleader were drawn upon a sledge from Newgate to Coleman Street. At the gallows erected outside their meeting house Venner proclaimed that ‘what I did was according to the best light I had, and according to the best understanding that the Scripture will afford’. Refusing to confess he insisted that all the doctrines he had preached were the truth. Together with his companion, a button-seller by trade, Venner was hung, drawn and quartered. Within days eleven more Fifth Monarchists were hung and beheaded. Their heads were set on London Bridge and their dismembered bodies on four of the city’s gates. King Jesus had not come.

.

Wonderful Post! So insightful and interesting, thank you so much Ariel!

Definently a really nice suprise read for what was about to be a bleak sunday.

I covered the Fifth Monarchists in college and yet was never personally inclined or otherwise pushed to take their revolt seriously and it was instead taught as the equivalent as the street preachers at stratford warning commuters about endtimes but quite a bit more violent.

In retrospect I'm sure that was done to make things more digestible but it doesn't make it any less of a disappointing memory after reading this piece.

Of course that's more indicative of how breif things have to be at A-Level which is a shame. They're revolters in their own right not so drastically different than any protestant or catholic uprising.

Odd to think I was ever so dismissive of a religious uprising in a time where religious uprisings are focal to the era. Still I've said and done stupider things and will continue to do so, one of those magical things about being alive.

Thanks for the good read Ariel!