II. From the Norman Conquest to the Expulsion of 1290

The question of when Jews first came to England has been debated by historians for more than three centuries. They have noted that Jews were referred to by Bede in his biblical commentaries, in seventh- and eighth-century ecclesiastical decrees, as well as in a law of Edward the Confessor – unless this was an interpolation. Even so, the evidence we have suggests that Jews arrived in significant numbers after the Norman Conquest, emigrating from Rouen and probably settling in London about 1070. Moreover, if later seventeenth-century sources are correct, there were Jews at Cambridge in 1073 and Oxford in 1075. This is certainly possible for the Domesday Book of 1086 mentions a man named Manasses living at Oxford.

Anthony Wood, The History and Antiquities of the University of Oxford (ed. John Gutch, 2 vols., Oxford, 1792 – 96), vol. 1, p. 129

By the mid-twelfth century an important community had been established at London in the area now known as Old Jewry, with smaller if sometimes densely populated Jewish neighbourhoods at Lincoln, Norwich, Gloucester, Northampton, Winchester, Cambridge, Oxford, Bristol, Colchester, York, Bungay, Thetford and elsewhere. Like Castile and Aragon, where there was no legislation requiring them to dwell within a walled quarter, urban Jews lived among rather than separated from Christians. Although we lack precise figures, modern estimates of the size of medieval England’s Jewish population at its peak range between 3,000 and 5,000. Following mass emigration and conversion to Christianity in the 1250s, however, this number fell sharply. So much so, that by the 1280s the adult Jewish population may have been fewer than 1,200. This was considerably less than the 17,511 or 16,511 or 15,060 Jews that various chroniclers, antiquaries and polemicists reckoned were expelled in 1290.

Raphael Holinshed, The third volume of the Chronicles (1587), p. 285

We know that English Jews were described as physicians, goldsmiths, soldiers, vintners and fishmongers, and that a significant number were merchants and scholars. Royal charters issued by Henry II and confirmed by his successors granted them freedom of residence, passage, the right to possess and inherit land, loans and property, as well as nominal judicial privileges. With time, however, Jews generally became associated with lending money at interest because the Papacy condemned usury as a sin (Exodus 22:25–27, Leviticus 25:35–37, Deuteronomy 23:19–20, Luke 6:35); Church councils later compared it to homicide, sodomy and incest.

Caricature of the Norwich Jews, Mosse-Mokke and Avegaye. Rolls of the issues of the Exchequers, Hilary term 1233 (17 Henry III). The National Archives, E 401/1565

Unfortunately, the history of medieval English Jewry contains many instances of religious persecution. In 1189 the Archbishop of Canterbury recommended that Jews should not attend Richard I’s coronation at Westminster for fear of witchcraft. When they were sighted bringing presents to the new King a riot ensued during which some were murdered, one forcibly baptized and their London homes looted and burned. The following year a mob led by barons, clergymen and soldiers recruited for the Third Crusade massacred most of the Jewish population of York. Similar pogroms were perpetrated at Lincoln, Dunstable, Colchester, Lynn, Stamford, Thetford, Ospringe and Bury St. Edmunds – from where, at the abbot’s instigation, Jews were expelled. Afterwards there were expulsions from Leicester in 1231, Newcastle in 1234, Wycombe in 1235, Southampton in 1236, Berkhamsted in 1242, Newbury in 1244, Derby in 1263 and Marlborough, Gloucester, Worcester and Cambridge in 1275. Added to this was the imposition by the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 of distinctive clothing on Jews; a piece of saffron-coloured fabric in the shape of the two tables of the law.

Representation of a Jew from Colchester, wearing the prescribed Jewish badge, 1277; the drawing is labelled ‘Aaron, son of a devil’

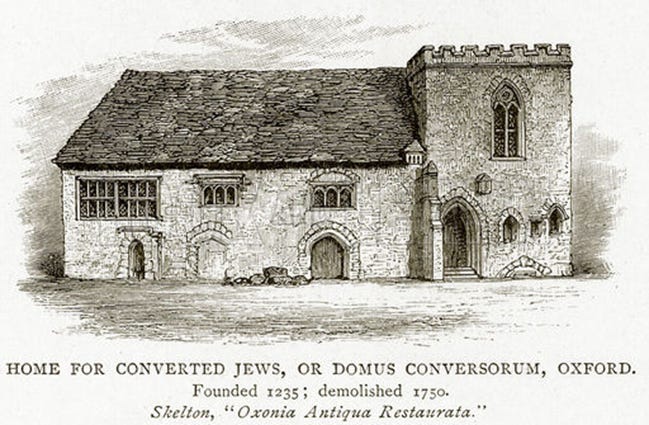

Though initially not widely observed this regulation must be seen in the context of increasingly aggressive preaching by Dominicans and Franciscans; the foundation in 1232 of a House for Jewish Converts (Domus Conversorum); and severe anti-Jewish legislation proclaimed in 1253 and renewed with the Statute of de Judaismo in 1275. Furthermore, during the Baron’s Wars of 1263–67 Simon de Montfort’s supporters killed Jews and destroyed their properties in London, Canterbury, Worcester, Ely and Northampton. Rumours even circulated that Jewish women accepted baptism to save themselves. According to contemporary accounts in 1278–79 Edward I had about 290 Jews indicted, convicted and executed in London for coin clipping. Equally horrific were accusations of ritual murder, notably following the disappearance of William of Norwich just before Easter 1144. Similar charges were made at Gloucester (1168), Bury St. Edmunds (1181), Winchester (1192, 1225, 1232), Norwich (1230), London (1244) and Northampton (1279). But the most famous case was the alleged crucifixion of Hugh of Lincoln in 1255, which resulted in the execution of nineteen Jews.

St William panel; rood screen, Holy Trinity church, Loddon, Norfolk, c.1450–c.1525

Several reasons have been suggested for why Edward I expelled Jews from England in 1290. Observers variously attributed it to the influence of the Queen Mother, baronial complaints in Parliament and advice from the King’s council. Among modern historians the traditional view was that the Crown benefited financially: since Jews were legally the King’s property debts due to them became payable to him. Yet the contrary has also been maintained: once Jews were barred from usury in 1275 their wealth declined and consequently they became less useful to the Crown as a source of revenue through taxation. This argument is supported by the growing importance of foreign financiers, above all Lombards, Cahorsins and Gascons, upon whom Edward I became increasingly dependent for borrowing money. Nonetheless, it must be noted that after 1275 Jews – particularly in Norwich, Lincoln and Canterbury – were still engaged in usury disguised as trading in grain and wool. Indeed, some scholars think the practice was so widespread that Edward’s response was to force out Jews from his realm. Moreover, there is a European dimension to consider: King Philip Augustus of France had driven Jews from his lands in 1182 (only to readmit them in 1198); Edward himself had expelled Jews from Gascony in 1287; while Jews were also expelled from Anjou and Maine in 1289. Precedents had been set, but monarchs do not live forever.

Marginal illustration from the chronicles of Offa showing Jews being persecuted (13th century) [British Library, MS Cotton Nero D. I., fol. 183v]

III. From the Expulsion of 1290 to the expulsions of the 1490s

Following Edward I’s death six Jews led by a physician or Rabbi named Master Elias returned to England pleading for readmission. Although unsuccessful, there is a tradition that Jews secretly re-established themselves in England until their discovery in 1358. Similarly, for much of the fourteenth century Jews were periodically ejected from French territory – usually by royal edict – only to be readmitted; once to recover Jewish debts; once in return for large payments to the Crown and on condition that they did not practise usury; once to help pay an enormous ransom. Therefore it is no surprise to learn that we have fragmentary evidence for the presence of Jews or people of Jewish origin in England during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

In 1290 more than eighty Jewish converts to Christianity were living in the building provided for them in London. Though food and winter fuel appear to have been scarce many chose to remain and by 1308 over fifty were still there. Indeed, it was not until 1356 that the last known survivor on English soil of the pre-expulsion community, Claricia of Exeter, died.

Another interesting example was John of Bristol, a converted Jew who taught Hebrew at Oxford around 1323. Furthermore, a Jew named Hagin was baptized at Nottingham in June 1325 and as Walter of Nottingham later became chaplain of the Domus Conversorum. Also noteworthy are the handful of Lancashire deeds from 1298, the 1320s and 1331 witnessed by John le Ju, Hugh le Jew and Thomas le Jew. As Thomas was a parish clerk it is likely that these men were either converts to Christianity or descendants of apostates. Moreover, Edward III granted one Johannes de Chastell (John of Castile?) an annual income in 1356 for renouncing Judaism.

D’Blossiers Tovey, Anglia Judaica: or the History and Antiquities of the Jews in England (Oxford, 1738), p. 223

Similarly, in 1389 Richard II gave money to a former Jew of ‘Cicilia’ (Sicily or perhaps Cilicia?) recently baptized into the Christian faith and christened Richard after his royal godfather. In 1391 a physician and surgeon known as Charles le Convers received royal protection that extended to his servants and property. The following year Richard II pensioned another baptized Jewish convert, who took the name William Piers.

John Stow, The Annales, or Generall Chronicle of England (continued Edmund Howes: London, 1615), p. 306

In October 1410 Richard Whittington, twice former Mayor of London who would become immortalized in the legendary story of Dick Whittington and his cat, obtained license to have a Jewish doctor attend his sick wife. The Jewish physician’s name was Sampson of Mirabeau (probably in Vaucluse), and though granted permission to stay in London for one year his patient died before this elapsed. On 27 December 1410 Henry IV issued a safe-conduct for Elias Sabot (Elijah ben Shabbetai), an important Jewish doctor from Bologna. He arrived with a retinue of ten servants and was granted royal protection for two years.

Thomas Rymer, Foedera (20 vols., London, 1704–32), vol. 8, p. 667

In February 1412 Henry IV naturalized another physician, David de Nigarellis of Lucca. He may have been of Jewish origin and was afterwards made Warden of the Royal Mint. In October 1421 during the reign of Henry V an Italian apothecary named Job and his son John settled in England. They too were naturalized, but only after submitting to baptism. Even so, they were not among the four residents of the House for Jewish Converts recorded that year.

It was not only Jewish medical practitioners, however, who travelled to England. About 1468 a Portuguese adventurer arrived who on converting to Christianity was named Edward Brampton. Christened after his godfather Edward IV, for whom he fought, Brampton later served Richard III before returning to Portugal in March 1485 to negotiate a marriage for the recently widowed and, as events transpired, last Plantagenet king of England. Following the death of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth on 22 August 1485 and the subsequent marriage of the victor, Henry VII, a new Tudor dynasty was established. So in the next part of this series we will look at the fortunes and depictions of Jews and crypto-Jews in Tudor England.