liberty (noun, 1): freedom or release from slavery, bondage or imprisonment – including arbitrary, despotic or autocratic control [Oxford English Dictionary]

British Library, MS Cotton. Augustus II.106, Magna Carta, 1215

English history is full of myths.1 That shouldn’t surprise us because quite a large part of modern English national identity is based upon what, collectively, we believe happened in the past rather than upon what actually happened – at least so far as we can tell. Our job obviously gets harder when there are fewer sources to deal with. It’s also difficult because what sources we do have come loaded with their own sets of problems. Bias, of course, is the best known. But there are others too.

Manga Carta (London, [1539])

I. Rule of law

Unfortunately Magna Carta has several myths attached to it. When we talk about it today what we are essentially celebrating is the triumph of the rule of law over arbitrary power. Whether that power was abused by monarchs, heads of state or politicians amounts to the same thing. This view has a long history. And it’s best expressed, I think, by an anonymous pamphleteer who saw himself as the voice of the people: our ancestors had paid a heavy price in blood over hundreds of years to wrest these concessions from the Crown. But what they got was part of their birth-right, namely a ‘brazen wall, and impregnable bulwark that defends the common liberty of England from all illegal & destructive Arbitrary Power whatsoever, be it by either Prince or State endeavoured’.

Anonymous, Vox Plebis, or, The Peoples Out-cry (1646), p. 9

Yet it’s telling that this quotation comes from 1646 during the height of the English Revolution. And that’s because an appeal to this ‘Charter of our liberties’ reveals how a particular sense of the past was used to great effect in contemporary political struggles at a crucial moment – a moment when Parliament’s armies had defeated the Royalists on the battlefields of England and Wales, but the way in which the kingdom would be governed was still up for grabs. Indeed, I’d go further and suggest that the popular view of Magna Carta largely derives from the ways in which it was mythicized during these seventeenth century conflicts; first between Parliament and the early Stuart monarchy; and then between those on the winning side.

II. 1215 and after

In The Flowers of History the chronicler Roger of Wendover (d.1236) reported that:

King John, when he saw that he was deserted by almost all, so that out of his regal superabundance of followers he scarcely retained seven knights, was much alarmed lest the barons would attack his castles and reduce them without difficulty, as they would find no obstacle to their so doing; and he deceitfully pretended to make peace for a time with the aforesaid barons, and sent [the] earl of Pembroke, with other trustworthy messengers, to them, and told them that, for the sake of peace, and for the exaltation and honour of the kingdom, he would willingly grant them the laws and liberties they required; he also sent word to the barons by these same messengers, to appoint a fitting day and place to meet and carry all these matters into effect. The king’s messengers then came in all haste to London, and without deceit reported to the barons all that had been deceitfully imposed on them.

Accordingly, on 15 June 1215 in a meadow between Windsor and Staines known as Runnymede, John granted a series of concessions to these rebellious barons. A formal royal grant based on these agreements became known as Magna Carta.

Coronation of King John, as depicted in a copy of Matthew Paris’s chronicle [Chetham’s Library, Manchester]

Following John’s death in October 1216 and the accession of the infant Henry III the ‘Great Charter’ was reissued by the regent with several significant modifications and omissions. These changes restored a number of powers to the Crown, including the right of taxation. Further changes were introduced in 1217 and again in 1225, when the original sixty-three chapters were reduced to thirty-seven.

The National Archives, Magna Carta, 1225

In 1297 Magna Carta was reconfirmed by Edward I, who directed his justices to administer it as common law. Although the provisions of the Charter became antiquated with the passage of time they still remained in force. Indeed, they were seen as representing a fundamental and inalienable aspect of the law.

III. Sir Edward Coke

But the transformation of Magna Carta from an important document into an icon was mainly the achievement of one man. He was the jurist Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634). And it was during a Parliamentary debate in 1628 about mooted limitations to the Petition of Right – another landmark legal concession gained from the Crown – that he declared ‘take we heed what we yield unto, Magna Charta is such a Fellow, that he will have no sovereign’.

Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634)

According to Coke, the charter served to check tyrannical impulses. Indeed, its major tendencies were towards:

the honour of God, the safety of the king’s conscience, the advancement of the Church, and amendment of the kingdom, granted and allowed to all the Subjects of the Realm.

Charles I understood this too. Reportedly fearing that it may be somewhat prejudicial to his prerogative power, he accordingly prevented publication of Coke’s exhaustive commentary on Magna Carta. For Coke was held to be an exceedingly great ‘oracle amongst the people, and they may be misled by anything that carries such an authority’. Consequently Coke’s commentary remained in manuscript during the author’s lifetime and was issued posthumously by order of Parliament as the first exposition of The Second Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England (1642). Unlike the ‘private interpretations’ offered by advocates in their glosses and commentaries, Coke claimed that his explanations were based upon ‘the resolutions of Judges in Courts of Justice in judicial courses of proceeding, either related and reported in our books, or extant in judicial records’. All the same, it’s worth emphasizing that the charter Coke revered was not the original of 1215 but the amended 1225 version.

IV. Every Englishman’s legal birth-right

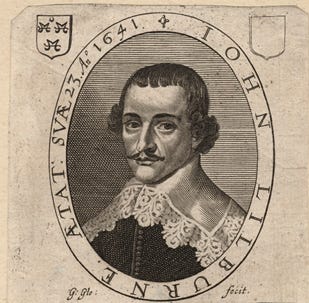

Coke’s views influenced a number of prominent lawyers. Echoes of them can also be found in the writings of John Lilburne, an irrepressible argumentative radical whose political movement the Levellers would be defeated but whose ideas are still celebrated today.

John Lilburne, aged 23

Initially Lilburne regarded the ‘Grand Charter of England’ as every Englishman’s legal birth-right and inheritance (would that he said woman too), a binding contract purchased by a sea of blood that maintained the boundary between sovereignty and subjection. His enthusiasm, however, was to be tempered by the arguments of another future Leveller, William Walwyn. In an open letter addressed to Lilburne published as Englands Lamentable Slaverie (1645), Walwyn warned that Magna Carta was misnamed: it was a deceitful and improper term to blind the people. For Walwyn the charter constituted just an aspect of the people’s rights and liberties that had been wrestled out of the paws of kings. Drawing on another potent myth, namely that ever since the Norman Conquest the English people had lived under the weight of an arcane, burdensome and expensive legal system – the so-called Norman yoke – Walwyn dismissed Magna Carta as but ‘a beggarly thing, containing many marks of intolerable bondage’. Accordingly, Lilburne conceded that although ‘the English man’s inheritance’ had cost ‘our forefathers’ a great deal of blood and money before they could wring it out of the hands of their tyrannical kings, yet the great charter fell far short of the laws enacted before the Norman Conquest by Edmund the Confessor.

V. Chapter 29

Yet there remained some things worth championing: it was believed that Magna Carta enabled the ‘Commons of England’ to convene and sit in Parliament. Moreover, the twenty-ninth chapter of the charter of 1225 (clause 39 in the original) was interpreted as a confirmation of ‘all our privileges and liberties’. For these few words, thought Lilburne, embodied ‘the liberty of the whole English Nation’:

No Freeman may be taken and imprisoned, and disseized of his Free-hold, or his Liberties, or his free Customs, or be out-lawed, or banished, or any way destroyed: neither will we go upon him, neither condemn him, but by the lawful trial of his equals, or by the law of the land; Justice and Right we will sell to none, we will deny to none, nor will defer to none.2

John Lilburne, The Copy of a Letter (1645), p. 2

Coke’s reading of this clause had upheld the principle that commoners could only be convicted by their fellow commoners or according to the law of the land. Lilburne agreed, citing this interpretation when brought before the House of Lords (he claimed that he could not be tried by peers of the realm since they were not commoners).

It’s since become customary to read chapter 29 of Magna Carta as guaranteeing trial by jury to all Englishmen and women. As was pointed out in scholarly work to mark the 700th anniversary of the charter, however, the traditional interpretation needs to be modified. This is because the original Latin wording is ambiguous. Indeed, Coke’s interpretation was anachronistic since he viewed early 13th century law through a 17th century lens. If anything, this famous clause confused rather than clarified matters. After all, judgment by equals or by the law of the land was not the same as judgment by equals according to the law of the land.

VI. America

The English Revolution may have ended in failure with the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660. Yet some of its dynamic ideology was transplanted to North America – both immediately and eventually by way of the Glorious Revolution of 1688–89. When the American colonists came into conflict with the British crown they drew on this heritage in their impassioned rhetoric. So we find the Stamp Act of 1765 denounced by the Massachusetts Assembly as being ‘against the Magna Carta and the natural rights of Englishmen’. And the great charter was invoked again in 1779 by John Adams, who would become second president of the United States:

If in England there has ever been any such thing as a government of laws, was it not magna charta? And have not our kings broken magna charta thirty times? Did the law govern when the law was broken? or was that a government of men?

Even today, one prominent legal historian has noted that Magna Carta continues to be widely cited in American judicial opinions – notably in the right to trial by jury; in the right to speedy and adequate justice; and on the question of proportionality in punishment.

Meanwhile, in England of the 63 original clauses of the 1215 charter four are still valid today – 1 (part), 13, 39 and 40. This includes the two most famous clauses:

No free man is to be taken or imprisoned or disseized or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined, nor will we go or send against him, except by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land (clause 39 of 1215 charter; clause 29 of 1225 charter).

To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice (clause 40 of 1215 charter).

[translations by J.C. Holt, Magna Carta (Cambridge, 3rd edn., 2015), p. 389]

Certainly then there is still something to celebrate and uphold. But we should also accept that our shared perception of Magna Carta owes more to events in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries than the thirteenth century.

Magna Carta memorial at Runnymede, erected in 1957 by the American Bar Association

Originally published as ‘6 Magna Carta myths explained’, History Extra (12 June 2015) http://www.historyextra.com/article/medieval/6-magna-carta-myths-explained.

Cf. Magna Charta, Cvm Statvtis (1618), fol. 5v, ‘Nullus liber homo capiatur, vel imprisonetur, aut disseisietur de liber[o] tenem[en]to suo, vel libertatibus, vel liberis consuetudinibus suis, aut utlagetur, aut exuletur, aut aliquo modo destruatur, nec super eum ibimus, nec super eum mittemus, nisi per legale judicium parium suorum, vel per legem terræ. Nulli vendemus, nulli negabimus, aut differemus justitiam, vel rectum’.

Fascinating analysis! Two phenomena come to mind: firstly, in Australian politics and culture the disastrous campaign at Gallipoli in World War One became the “Gallipoli myth” during the Vietnam War when ordinary Australians perceived themselves (rightly) to be dragged, yet again, into a pointless meat grinder. The unfortunate consequence was that a culture and society that produced some of the very best fighting troops in the world were demoralized and came to see themselves as victims, losing most of their vigour and fighting spirit in the process. An even more extreme situation unfolded with the Kiwis. The point was that an historical event was reinterpreted later and only then acquired its enduring national significance.

The second phenomenon that comes to mind is how the understanding of the Hebrew Tanakh interacted with historical events subsequent to the writing of its various sections and its meaning continued to evolve in a constantly relevant and ever-fresh meaning that inspired and consoled its adherents. Scholars, beginning with the mainly German scholars of the 19th century mocked what they considered naive and inaccurate interpretations of these sacred texts, but the historical achievements of those inspired by these evolving understandings of these ancient texts have changed the world, overwhelmingly for the benefit of humanity.

Your article about the Magna Carta reveals a similarly beneficial process by which momentous political and social benefits were the result of an evolving interpretation rather than a strict historically faithful academic understanding.

Really enjoyed this. Many thanks.