The Muggletonians, 1652–1979? Part one

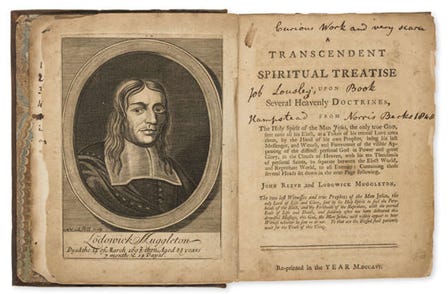

It was on the mornings of 3, 4 and 5 February 1652 that the ‘Lord Jesus, the only wise God’ spoke to a man named John Reeve (1608–1658), revealing to him that he had been chosen as the Lord’s ‘last messenger’. Together with his cousin Lodowick Muggleton (1609–1698), who acted as Reeve’s mouthpiece – much as Aaron had served his brother Moses – the pair proceeded to claim that they were the ‘two Witnesses of the Spirit’ foretold in the Revelation of Saint John.

Both had humble origins. Reeve was most likely the son of a clothier from Clack, Wiltshire who had been apprenticed to a London haberdasher, although Reeve learned the trade of a tailor. Muggleton was the son of a farrier and had been born at the corner house in Walnut Tree Yard within the parish of St Botolph without Bishopsgate. He was apprenticed to a Merchant Taylor, gaining his freedom in February 1633 before wedding a young woman named Sarah (the first of Muggleton’s three marriages).

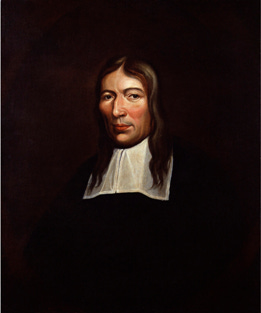

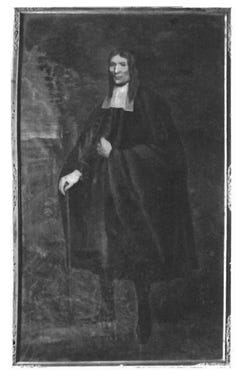

Lodowick Muggleton (c.1674), by or after William Wood

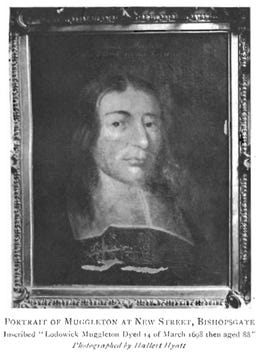

Samuel Cooper (1609–1672), ‘Portrait of a gentleman’ (no date); traditionally but probably erroneously identified as Lodowick Muggleton.[1]

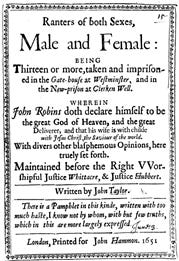

Shortly before the outbreak of the English Civil War both Reeve and Muggleton were living in the parish of Holy Trinity the Less where, on 30 May 1641, they signed the Protestation Oath. But besides some details about Muggleton’s personal life – he remarried following the premature death of his first wife – little more is known about them during the course of the following decade. On 4 February 1652, however, Reeve and Muggleton denounced TheaurauJohn Tany as a ‘counterfeit high Priest’ and pretended prophet, marking him as a Ranter, the spawn of Cain. The next day they denounced one John Robins, whom they accounted ‘that last great Antichrist, or man of sin, or son of perdition’ (Robins will be the subject of a future post).

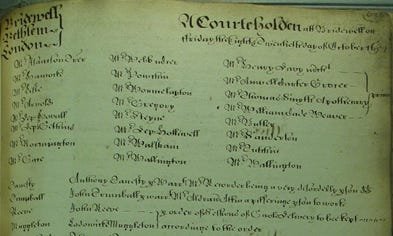

Despite, by their own accounts, successfully cowing and silencing their two great rivals, Tany and Robins – ‘Head of all false Christs, false Prophets, and false Prophetesses, that were in the world at that day’ – Reeve and Muggleton were themselves charged with blasphemously denying the Trinity. Accordingly, they were brought by warrant before the Lord Mayor of London and, following their examination, committed to Newgate gaol on 15 September 1653. There they remained for about a month before being removed to the Old Bailey ahead of a hearing at the London Sessions of the Peace. Accused of ‘despising’ and ‘railing’ against the ministry as well as blasphemously declaring that the man called Jesus who died at Jerusalem was ‘the only God and everlasting Father’, they were sentenced to six months imprisonment each in Bridewell. Having endured this punishment they were released on bail in mid-April 1654.

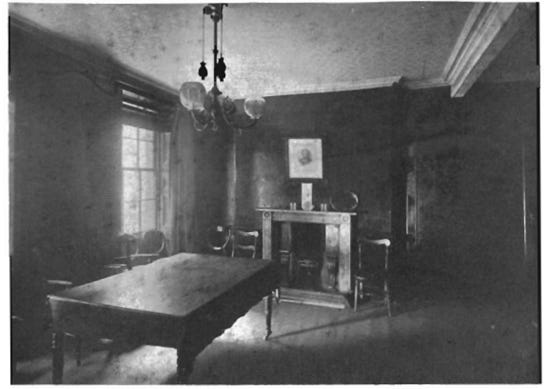

Court Minute book of Bridewell Hospital

Afterwards the Scottish biblical scholar Alexander Ross dismissed Reeve’s first published treatise as ‘full of transcendent nonsense and blasphemies’ which threatened the ‘very root of Christianity’. Indeed, Reeve and Muggleton were frequently abused and derided by their contemporaries. The earliest written accounts portray them as impudently holding ‘ridiculous’ beliefs, notably – and peculiarly – that God died and, by his own power, thereafter raised himself from death to life. They were regarded, moreover, as being ‘very high in their ranting principles’. Indeed, Reeve and Muggleton wrote a ‘strange’ letter to several eminent ministers in London and Westminster that was variously described as ‘ranting’, ‘canting and blaspheming’. For good measure they pronounced a journalist ‘cursed and damned both [in] soul and body unto all eternity’ for presuming to publish their ‘wild paper’ and complaining of the dangers of religious toleration. Undeterred, the journalist responded by confronting these ‘mad fellows’ only to hear them utter ‘many strange senseless blasphemies’, ‘extravagancies’ and ‘damnable doctrines’.

The Quakers were equally scathing, as is evident from their bitter and protracted pamphlet war against the Muggletonians. Although numerically far superior – there were perhaps as many as 60,000 Quakers by the early 1660s and probably never more than several hundred Muggletonians during the seventeenth century – a succession of prominent Quaker authors considered it necessary to refute Muggletonian calumnies, pretensions and doctrines in print. Thus in 1654 Edward Burrough responded to an epistle from Reeve by emphasising Reeve’s ignorance, confusion, self-deception, fallibility and mendacity. Similarly, Richard Farnworth maintained that Muggleton was an ‘unwise’, ‘unjust’ and ‘unmerciful’ judge disseminating ‘erroneous and false’ notions. George Fox too thought Muggleton a false prophet and blasphemous ‘heathen’ moved by a ‘rash, erring, lying, deceitful’ and diabolic spirit. Isaac Penington condemned Muggleton’s ‘dark imaginations’ and ‘lying lips’ which voiced reproachful, ‘slanderous testimony’. Josiah Coale declared Muggleton to be ‘a son of Darkness, and a co-worker with the Prince of the Bottomless Pit’. While William Penn denounced Reeve and Muggleton as ‘horrible’ impostors whose beliefs were inconsistent with Scripture, contradictory and against reason.

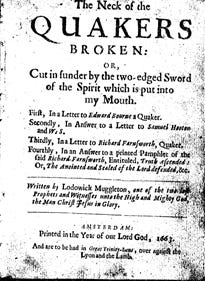

By this time Reeve was dead. But Muggleton responded with The Neck of the Quakers Broken (1663), a work published in London despite bearing a false Amsterdam imprint. So vitriolic was this rebuttal and so blasphemous its contents, that Muggleton was indicted in January 1677. He was found guilty, sentenced to stand upon the pillory in three prominent places in London; duly pelted with clay, rotten eggs, oranges, bottles and stones; had his books burned before his face by the common hangman; and fined the enormous sum of £500.

Once more contemporary reaction was overwhelmingly hostile. Hence accounts of his trial and punishment depicted Muggleton as a low-born, ignorant, nonsensical, obstinate, impudent and ‘factious’ fellow. This notorious ‘grand impostor’ and ‘superlative monster of wickedness’ was, in the opinion of pamphleteers, either the ‘boldest wretch that ever the earth made known’ or nothing but ‘a poor silly despicable creature’; a bold enthusiast who had ‘easily seduced’ several weak and unstable people (‘especially of the female sex’) with his nauseous dunghill of ‘horrid blasphemies’. Seventeen years later Muggleton’s ‘absurd, false, and precarious’ doctrines were again reviled as the ‘fruits of ignorance, confidence, and imagination’. His pretensions to divine illumination, along with those of his co-heresiarch Reeve, were also scorned:

If confusion and self-contradiction may pass for Exposition; if confidence and self-assuming may pass for Inspiration; if nonsense and obscurity may pass for Illumination; if cursing and damning others may pass for Charity; if Blasphemy may pass for Religion; then these two may be allowed to be what they pretend.

Plaster cast of Lodowick Muggleton’s death mask.[2]

By the time of Muggleton’s death in March 1698 followers such as Thomas Tomkinson had taken on his mantle, defending the sect’s reputation in print. Yet rather than diminishing, the criticism took a fresh turn: Muggleton was now likened to his enemies the Quakers, all upheld as examples of subtle, hypocritical enthusiasm. The tone remained the same through much of the eighteenth century: Muggletonian principles of faith were derided as a mad medley of impudent, ignorant blasphemous nonsense. At the beginning of the nineteenth century few except the similarly abused Swedenborgians, with whom Muggletonians shared some doctrinal affinities, notably their common rejection of orthodox Trinitarianism, had proved attentive. Nonetheless, according to Muggletonian sources, about 300 believers still kept the faith. They lived mostly in London and Norwich as well as in places in Derbyshire and Kent. If Muggletonian estimates are reliable rather than exaggerated then these numbers may have grown slightly over roughly the next fifty years. Thus in 1863 there were an estimated 250 to 300 Muggletonians in London and its suburbs, some 60 to 80 in Derbyshire, 12 to 15 in Nottingham, maybe half a dozen in Mansfield and a handful in Kent. Moreover, it was during the Victorian period that mockery gradually gave way to amused curiosity.

Eventually, following a fortuitous encounter in 1860 with a Muggletonian of Mansfield named William Risdale (1802–1885), the Unitarian minister Alexander Gordon (1841–1931) sympathetically set about rescuing this dwindling faith – erroneously assumed extinct by some – from obscurity. Through Risdale Gordon was introduced to the Muggletonian leadership in London. He learned that they had no meeting place of their own. Rather, ‘they met in private houses or at friendly inns, where their book-closet was stored’. Then on 14 February 1870 about forty of them met to celebrate the commencement of their ‘Great Holiday’, being three days of festivities to commemorate the foundation of their sect. These were held at newly acquired leasehold premises subsequently described as an old Georgian house. The exact location, 7 New Street, Bishopsgate supposedly stood on the site of what was once Walnut Tree Yard, where Muggleton had been born. Significantly, Gordon was also present at these celebrations recalling that ‘for the first time’ in Muggletonian history ‘a stranger’ had been permitted to attend. During the following week Gordon was also granted permission to examine ‘the curious store of manuscripts in the possession of this singular survival from the numerous sects of the Commonwealth period’.

The Muggletonian reading room in New Street, Bishopsgate; early 20th century photograph reproduced in George Charles Williamson, ‘Lodowick Muggleton’ (1919), between pp. 64–65

Yet during the next forty years or so Gordon revisited the Muggletonian premises only once, until in 1914 he felt compelled to return. As expected, all his ‘old friends’ were dead and Gordon ‘wondered what successors they had, for these believers do not proselytise, nor do they attempt to bias their children in favour of their tenets’. Even so, the caretaker of the Muggletonian meeting place proved to be the granddaughter of a ‘friendly and kindly old soul’ whom Gordon had known from his previous visits. Following a cup of tea with the community’s recognised leader Gordon was invited to the upstairs meeting-room on 14 February 1914 – not only Valentine’s Day but the opening of the Muggletonians’ ‘Great Holiday’. The room itself looked entirely unchanged. Dominating the setting from its situation beside the fireplace was a ‘full-length painting’ of Muggleton done by his friend William Wood. On the opposite wall was an oil painting depicting the supposed likeness of Jesus in profile, as portrayed in the apocryphal letter of Lentulus.

Full-length portrait of Lodowick Muggleton by William Wood of Braintree, Essex (early 20th century photograph)

Lodowick Muggleton’s portrait displayed in the Muggletonian reading room at New Street, Bishopsgate (early 20th century photograph)

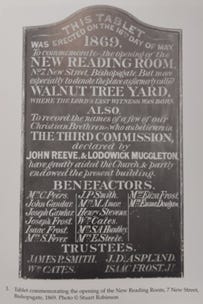

There was also a tablet recording the names of benefactors. But of those present at the ‘ample and pleasant social meal’ their number had dwindled to about twenty. Despite this freely admitted numerical decline, Gordon observed that it was no indication of how many believers still lived.

Tablet commemorating the opening on 16 May 1869 of the new Muggletonian reading room at no. 7, New Street, Bishopsgate [image taken from William Lamont, Last Witnesses (2006)].[3]

Just over sixty years later, intrigued by a reference in one of Gordon’s published lectures on the Muggletonians, the historian Edward Thompson (1924–1993) was ultimately able to recover the sect’s archive. This story is relatively well-known and has been told before.[4] Yet as we shall see in part two of this essay, not only is there much more to add but in several places also aspects that must be modified.

[1] In the early twentieth century this watercolour miniature was said to have been ‘fully authenticated by contemporary documents’. For many years it remained in the possession of some of Muggleton’s ‘descendants and followers’ in Derby until it was acquired by John Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913). It was sold at Christie’s, London in June 1935; at Sotheby’s, London in March 1965; and again at Sotheby’s on 28 April 2021 for an estimated £5,000–£8,000.

[2] At the beginning of the twentieth century this plaster cast was preserved at the Muggletonian reading room in Bishopsgate, London. Thereafter it came into the possession of George Charles Williamson, who donated it to the National Portrait Gallery in 1910.

[3] In July 1981 William Lamont and Mrs Jean Noakes came across this tablet in the barn of her old farm.

[4] Christopher Hill, Barry Reay and William Lamont, The World of the Muggletonians (London, 1983), pp. 1–5; E.P. Thompson, Witness Against the Beast. William Blake and the Moral Law (Cambridge, 1994), pp. 115–19; William Lamont, Last Witnesses. The Muggletonian History, 1652–1979 (Aldershot, 2006), pp. 7–8.

Really looking forward to part two!

Minorities are always interesting!